|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Weather Almanac for February 2012THE COLDEST PLACES ON EARTH

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Temperature |

| Antarctica, Vostok Station (Russia) | -89.2°C (-128.6°F) |

| Antarctica, South Pole (US Amundsen-Scott Station) | -82.8 °C (-117.0 °F) |

| Russia (Asian), Oymyakon | -67.7°C (-89.9°F) |

| Greenland, Northice | -66°C (-86.8°F) |

| Canada, Snag, Yukon | -63°C (-81.4°F) |

| United States, Prospect Creek, Alaska | -62.1°C (-80°F) |

| Russia (Europe), Ust’-Shchugor | -58.1°C (-72.6°F) |

| Mongolia, Uvs Lake | -57.8°C (-72°F) |

| United States (Contiguous States) Rogers Pass, Montana | -56.7°C (-69.7°F) |

| Afghanistan, Shahrak | -53.3°C (-64°F) |

| Kyrgyzstan, Astana | -53.3°C (-64°F) |

| Sweden, Vuoggatjalma | -52.8°C (-63°F) |

| China, Mohe | -52.3°C (-62.1°F) |

| Kazakhstan, Astana | -51.7°C (-61°F) |

| Finland, Kittilä | -51.5°C (-60.7°F) |

| Norway, Karosjok | -51.4°C (-60.5°F) |

| North Pole | -50.6°C (-59°F) |

It must be noted that the North Pole (geographic) lies within the Arctic Ocean and has no permanent, long-term monitoring station. Northice in Greenland was a British research station for two years in the early 1950s. A measurement by a remote weather station at Klinck, Greenland operated by the Space and Engineering Center of the University of Wisconsin, Madison between 1987-1992 registered a low temperature of -69.4°C (-92.9°F) on 22 December 1991. This reading has not been accepted by those charged with reviewing extreme weather records, but Burt feels this should be recognized as the coldest temperature on record for the Northern Hemisphere.

Verkhoyansk in Siberian Russia has often been cited as tied with the Oymyakon mark of -67.7°C (-89.9°F) on 6 February 1933 for the coldest reading in the Northern Hemisphere. This is true if we round off the readings to -68°C (-90°F). In fact, Verkhoyansk’s observation was -67.6°C (-89.7°F) on both 5 and 7 February 1892.

The Antarctic continent should contain many locations that have dropped below -50°C (-58°F). For example, a remotely monitored station in Queen Maud Land in the eastern Antarctic recorded a temperature of -70°C (-94°F) in 2003. That reading was coincidental with a wind blowing at 120 km/h (75 mph), which would give a windchill reading of -150 on the Fahrenheit scale, likely the coldest windchill ever calculated from measured data. Vostok Station’s monthly record cold temperatures show half of them (from April to September) are readings below -80°C (-112°F).

Note that these readings are based on regular meteorological observations, though some are remotely sensed. According to Burt, the US Army Natick Laboratory (that studies cold environments) left a minimum-temperature thermometer for nineteen years on Denali (Mt McKinley) in Alaska by at an elevation of around 4,572 m (15,000 ft). The coldest temperature indicated on that thermometer was reported to be -73.3°C (-100°F). Due to the nature of this instrument, no date could be assigned and there is no indication of how often temperatures approached this mark.

Other spot readings in specific environments have shown extreme cold temperatures may occur that threaten many of the accepted record cold marks. For example, two locations used in a University of Calgary permafrost study in a mountain valley near Fort Nelson, British Columbia reached unofficial lows of -71.1°C (-96°F) and-68.9°C (-92°F) on the nights of 6-7 January 1982. I would suspect that similar very cold readings could be found elsewhere at or near high mountain elevations such as Alaska’s Denali, Canada’s Mt Logan, Mt Everest, etc., or on the Greenland ice cap if regular readings were taken in such locations. The difference between the cold records at Vostok and South Pole are attributed in part to the higher elevation of Vostok.

Several factors combine to make some locations colder than others. I speak here of chronic cold places such as those mentioned above rather than “event” cold waves, which usually occur when the frigid air from those cold places moves out and settles elsewhere.

The first factor that should jump out at anyone seeing a pattern in the aforementioned cold places is the nearness to one of the two poles. Antarctica dominates the Southern Hemisphere’s cold places. Elsewhere in the hemisphere, their separation from the polar zone by ocean waters tempers the movement of cold air northward (for a Northern Hemisphere resident, that feels a bit odd to say).

In the Northern Hemisphere, most of the cold places occur on the continents north of the Arctic Circle, with the coldest located some distance south of the North Pole. This is because the North Pole sits within the Arctic Ocean, which adds heat to the surface and thus tempers the cold.

The prime factor for the polar regions being the “poles” of winter cold stems from the fact that these areas are without direct sunlight during the Winter months of the year, and even in the transition periods of early Spring and late Autumn, the sun’s incoming energy is weak by mid-latitude and tropical standards. If we ignore heat transportation from more temperate areas toward the poles — an important process in the global heat budget — incoming solar radiation is the major source of heat in the local heat budget.

[The heat budget is the equation that combines sources of heat input and heat loss to determine a locale’s air heat content, or temperature. It is analogous to an economic budget where income and expenses determine the amount of money available for extra spending (and savings).]

In addition to the solar input, heat may be gained by radiation from other sources such as the water vapor and other gases in the air (the so-called greenhouse gases) and any condensation or deposition of water. Heat is lost by its radiation from the surface to the atmosphere above. As mentioned above we are ignoring heat transported in by the winds from elsewhere as well as any heating that might occur from air descending from above or from the underlying bedrock. We will also ignore heat lost through air movement out of the region and through evaporation or sublimation as these are small components during the winter.

A snow or ice surface is an excellent radiator of heat away from its surface. Since a snow cover is common in these cold areas, the rate of radiative heat loss by the surface air is about as great as it can be (70 to 90 percent). That radiative (infrared) heat loss moves into the atmosphere above; and some escapes to outer space, and some is captured by the gases and liquids of the air at altitude. Atmospheric water, in both the gaseous and liquid states, is one of the best at absorbing heat radiation, and once the heat is absorbed, the water will re-radiate it. Some of that reradiated energy will head back to the surface and the rest further out into the atmosphere. A similar process takes place with those greenhouse gases.

The net effect is that some of the heat energy radiated away from the surface is returned by back-radiation of the atmospheric constituents, particularly water. Therefore, a cold area often has very low water vapor content in its air (low absolute humidity) and a lack of cloud cover. This assures the greatest radiative heat loss from the surface.

Now we have minimal radiation input and maximum radiative heat loss to give a strong negative tilt to our heat budget (it is running a strong deficit just like most nations). To increase the degree of cold, the region should be as cut-off as possible from any source of heating brought in by the wind (advective heating). In the Antarctic, the size of the continent and its constant cover of ice and snow do an effective job of preventing air from the tropical regions from reaching the continent’s interior. In the Northern Hemisphere, the Siberian and Canadian/Alaskan cold regions are effectively cutoff from much of the warm air advection from the south by some of the tallest, and youngest, mountain ranges in the world: the Himalayas and the Pacific Coastal Ranges of North America respectively.

Finally, elevation plays a strong factor in producing cold regions. As we saw above, the higher elevation of Vostok Station on the Antarctic highland plateau is a factor in it being colder than the slightly lower South Pole. The most obvious example of greater cold at elevation can be found in the classic pictures of Mt Kilimanjaro’s snowy peak rising over Equatorial Africa. As well, during most years snow falls at the summits of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa in Hawaii. A climate study at Peter Sinks in the Wasatch Mountains of northern Utah recorded a low of -56.3°C (-69.3°F) on 1 February 1985; a reading not far off the US record for cold outside Alaska.

With all the continent, save a small portion of the Antarctic Peninsula, lying within the Antarctic Circle, Antarctica ranks first as the coldest continent, and the driest. As seen, its record low temperatures are significantly colder than any recorded elsewhere on the planet. Similarly, climate averages are also the coldest in the world with many sites such as the South Pole and Vostok never rising above the freezing mark.

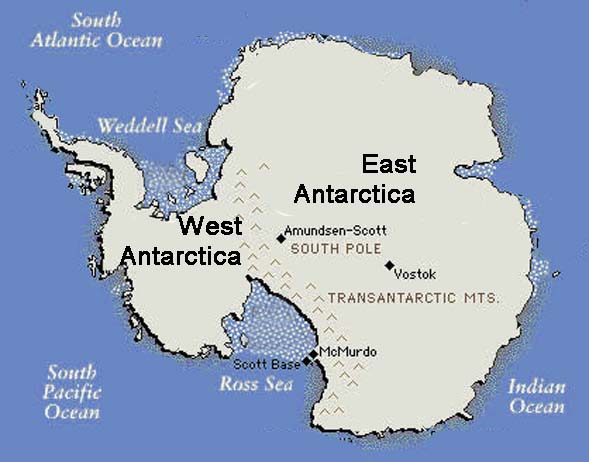

Russia's Vostok station sits on the Eastern Antarctic Plateau 1300 km (812 miles) from the geographic south pole, and near the south geomagnetic pole, at an elevation of 3,488 metres (11,444 ft) above sea level. Vostok is at the center of the huge East Antarctic Ice Sheet. America’s Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station sits near the geographic pole on the high plateau of East Antarctica at an elevation of 2835 m (9301 ft). Because of its proximity to the geographic pole, Amundsen-Scott is the only inhabited place on earth where the night and day lengths are nearly 6 months long. (Due to refraction by the atmosphere, the sun visibly arises 4 days before the spring equinox and sets 4 days after. Thus “day” is about 8 days longer than “night”.)

Vostok holds the record for the coldest place on Earth, having dropped to a low temperature of -89.2 °C (-128.6 °F) on 21 July 1983. The daily mean temperatures during meteorological winter (June-July-August) here is below -65°C (-85°F) with average daily low temperatures between -68.8°C (-91.8°F) and -71.6°C (-96.7°F) during these months. (September is actually colder than June with an average low of -70.3°C (-94.5°F) and daily mean of -66.1°C (-87°F).) The coldest single month at Vostok occurring in August 1987, with an average temperature of -75.4°C (-104°F). Vostok’s record high temperature is -12.2°C (+10°F), reached on 11 January 2002.

| Location | Temperature |

| Antarctica, Vostok Station (Russia) | -89.2°C (-128.6°F) |

| Antarctica, South Pole (US Amundsen-Scott Station) | -82.8 °C (-117.0 °F) |

(These cold records could be in jeopardy. In 2005, the Americans placed an automatic station on Dome A (Argus), a site on the summit of the East Antarctica ice sheet, northeast of the South Pole and 1200 km (750 miles) inland from the coast. It sits at an elevation of 4091m (13,422 ft) that is about 600m (1967 ft) higher than Vostok. During its first five years of operation, the coldest temperature recorded at Dome A was -82.5°C (-116.5°F), not much off the South Pole record cold mark.)

At the Amundsen-Scott Station, the average daily low temperate falls below -60°C (-76°F) from April through September with the coldest reading ever recorded at -82.8 °C (-117.0 °F) on 23 June 1982. The warmest temperature at the South Pole was observed on Christmas Day 2011: -12.3°C (9.9°F).

Most of the continent’s surface is covered with ice and snow that averages over 1.6 km (one mile) thick. Seventy percent of the world’s fresh water is locked in that ice, which accounts for 90 percent of the global ice. At the South Pole, the ice is about 2850m (9350 ft) thick. The average ice thickness for the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is 2450m (8032 ft) and 2160m (7080 ft) for the full continent.

But little of that water is in the atmosphere, which is as dry as any desert. The average annual precipitation at the South Pole is only 10 mm (0.4 inches) while Vostok is 20.8 mm (0.82 inches), and the annual average for the continent is estimated to be about 166 mm (6.5 inches), technically a desert. That average is greatly skewed by the much higher precipitation falling over the Antarctic Peninsula and along the coastline where average total precipitation is about five to six times greater per annum. Almost all of the precipitation falls as snow.

Clean ice and snow surfaces are strong radiators of long-wave (heat or infrared) radiation and are highly reflective of any solar radiation incident upon them. The Antarctic surface is thus losing surface heat through radiation to the upper atmosphere at a high rate. As a result, during the Antarctic early morning and evening (the early spring and late autumn months), most of the weak solar radiation is reflected away and not available to heat the surface. Even in the summer months, with 24-hour daylight, much of the solar radiation is reflected away and summer temperatures across the continent remain at sub-freezing temperatures inland from the coast. The warmest temperature ever recorded on the continent was 15.2°C (59.3°F) at the Argentinean research stations at Orcadas and Marambio, located on islands off the Antarctic Peninsula.

In the interior, the cold comes on strong and remains more constant over the “winter” than it does over the northern continents. Jack Williams in his book The Complete Idiot’s Guide to the Arctic and Antarctic refers to this as a “coreless” winter. To explain the point, consider winters in North America. There, a period exists, usually during mid to late January when average temperatures are coldest and thereafter begin to warm. If we were to graph the daily climatological means, it would look like a descending staircase that reaches a minimum — the core — and then begins to ascend.

In interior Antarctic, Williams says, the average daily temperature drops greatest in mid-autumn (April at the South Pole station) and then only slips down several more degrees during the winter. For the South Pole, the average low temperate falls in April to -61°C (-78°F) and slides to around -63°C (-81°F) for July, August and September. Vostok Station shows a similar trend with average April low temperature at -67.8°C (-90.4°F) and dropping into a range from -68.8°C (-91.89°F) to -71.6°C (-96.9°F) over June, July and August. In September, it “warms” slightly to -70.3°C (-94.5°F).

If the absolute temperatures of the Antarctic winters are not cold enough for you, we can factor in windchill to make you shiver more. (In fact, Antarctic explorer Paul Siple devised the first scientific concepts of windchill.)

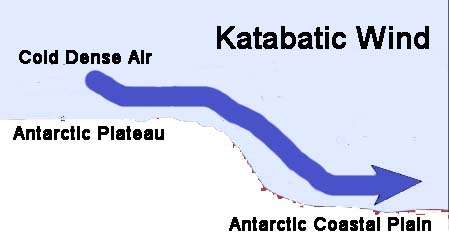

The extremely cold air over the Antarctic Plateau is also very heavy air (air becomes more dense as it becomes colder), and as it descends the elevation change heading off the plateau, its speed increases. This is called a katabatic wind and can reach speeds equivalent to those of a hurricane. Katabatic winds dominate the wind climate for most of the Antarctic continent away from the coast.

|

|

When a severe katabatic wind blows over the American research station at McMurdo Sound, it is referred to as a “Herbie.” The region between Black Island and White Island at McMurdo is known as “Herbie Alley” due to the ferocity of this windstorm that can blow there with winds up to 160 km/h (100 mph), which cut visibility to zero and produce dangerous windchill conditions. A Herbie can last for a few hours or several days.

Most windchill charts do not show values for temperatures anywhere near as cold as the Antarctic. Burt has written of one extreme case, however: an event remotely recorded on 4 July 2003 on Queen Maud Land in eastern Antarctica. For that period, the temperature was a bone-shattering -90°F (-67.8°C) with windspeed of 75 mph (120 km/h) that gave a windchill on the Fahrenheit scale of minus 193.

The average windspeed at Vostok blows around 18 km/h (11 mph) and has reached 97 km/h (60 mph). If we combine those with the warmest temperature ever recorded there (-12.2°C (+10°F)), we get windchill values of -20 and -27, respectively using the Celsius scale. At the average annual temperature at Vostok of -55°C (-67°F), the windchill is estimated to be -77 C scale (-107 F-scale) at the annual means for temperature and wind speed.

Chris Burt and others have used the term pole of cold to emphasis the coldest region in the Southern and Northern Hemispheres. There can be little debate that the East Antarctic plateau is the southern pole of cold. No place outside that continent is even in contention. And most would agree that the northern cold pole lies within Siberian Russia, though the honor is less distinct and could be in jeopardy if a permanent station was established on the Greenland ice cap.

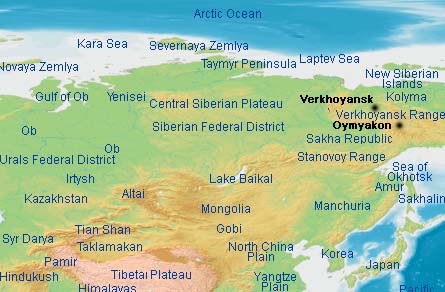

For most record books, two Siberian communities, Oymyakon (which has various English spellings) and Verkoyansk, hold the title of “Coldest Temperature in the Northern Hemisphere.” To repeat myself, this is true if the temperature is given in whole degrees Celsius (or Fahrenheit), but when we look down to the first decimal place, Oymyakon just edges her Siberian neighbor by a tenth of a degree: -67.7°C (-89.9°F) to -67.6°C (-89.7°F). Burt has listed a handful of Russian communities that have observed a temperature of less than -62.2°C (-80°F) — at least anecdotally — and all are found in eastern Russia between 60 and 70 degrees North.

There is no doubt that this area is cold, and not only on a single extreme reading, but in climatological means as well. Oymyakon is considered the coldest town on Earth. The extreme cold is notable in that the town sits south of the Arctic Circle by about 320 km (200 miles). It sits in a river valley at an elevation of about 690 m (2260 ft) above sea level between two mountain ranges. This topography allows cold air to drain downslope and accumulate in the valley. The annual daily mean temperature here is -16°C (3°F) but in January, that mean drops to -46°C (-51°F). The average daily low temperature in January is a numbing -49.8°C (-57.6°F). Daily record low temperatures lie below -60°C (-76°F) for the months of December, January, February and March, and November’s record not far off that mark.

| Location | Temperature |

| Russia (Asian), Oymyakon | -67.7°C (-89.9°F) |

Verkoyansk, the cold twin, actually lies northeast of Oymyakon, 118 km (74 miles) north of the Arctic Circle, along the Yana River valley. (This town has about twice the number of residents as Oymyakon.) The region is dry with generally clear skies, which enhance the formation of deep temperature inversions as cold air pools in the valley. The annual daily mean temperature here is -14.7°C (5.5F) that in January, drops to -45.8°C (-50.4°F). Like Oymyakon, record daily low temperatures fall below -60°C (-76°F) in December, January, February and March, with April and November only a few degrees off.

Interestingly, the highest summer mean temperature in Verkoyansk is 16.0°C (60.8°F). This produces a temperature range of almost 62 Celsius degrees (139 Fahrenheit degrees) in mean temperature between the coldest and warmest months. The range becomes even greater when we look at absolute temperature extremes. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, Verkoyansk holds the distinction of the most extreme temperature spread on Earth with a low of -67.6°C (-89.7°F) and peak high of 37.3°C (99.1°F), a range of 104.9 Celsius degrees (188.8 Fahrenheit degrees).

Although these two locations sit rather far south of the North Pole and straddle the Arctic Circle, they are extremely cold in the winter. Much of this cold results from the large Siberian high pressure cell that builds over the region each winter. This extremely cold air mass arises from the loss of heat during the cold season due to its ice- and snow-covered ground and a lack of strong solar radiation. The area is effectively cut off from intrusions of warmer tropical air or warm maritime air during the winter by the mass of east-west running mountain ranges to the south that includes the Himalayans, and the north-south Ural Mountains to the east and the Great Khingan Mountains to the west. Much of Siberia sits on high plateau, adding the element of elevation to the mix. As the cold and dry air mass builds, it enhances the loss of radiation to space by being both very dry and cloud-free. (Winter precipitation here totals less than 10 mm (0.4 inches) per month.)

The weight of this cold air pressing on the surface brings extreme high pressure to the region. The world record for highest sea-level pressure, according to the World Meteorological Organization is 1083.3 mb (32.01 inches Hg) at Agata Lake, Russia on 13 December 1968. However, that record may have been broken at Tosontsengel in northwest Mongolia on 19 December 2001. This site, also under the influence of the Siberia High, saw the pressure rise to 1085.6 mb (32.06 inches Hg). At the time of the measurement, the thermometer registered around -40°C/°F.

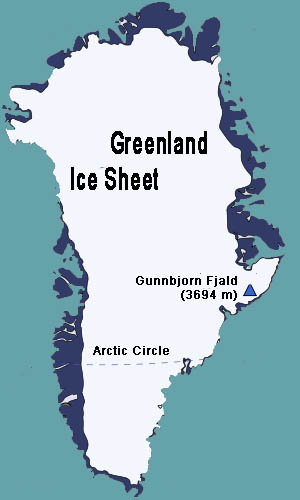

Greenland is also the only location in the Northern Hemisphere with a permanent ice sheet, which covers over 80 percent of the island. Ironically, the northernmost part of the island, Peary Land, is not covered in an ice sheet. There, the annual precipitation is too low to produce and maintain a deep layer of ice. The ice sheet centered over the island measures 2500 km long (1500 miles) and 1000 km (600 miles) wide at its longest extent and flows outward toward the surrounding seas in all directions. At its peak, the ice is around 3 km (10,000 ft) thick. Enough ice sits on Greenland, that if all were melted, it would raise global sea level over 7m (23 ft).

| Location | Temperature |

| Greenland, Northice | -66°C (-86.8°F) |

| North Pole | -50.6°C (-59°F) |

In this southwestern part of Greenland, where most of the population resides, the winter mean temperature drops to -30°C to -25°C (-22°F to -13°F), cold by most standards, but balmy compared to the island’s interior. In the Greenland interior where summer temperatures occasionally push past the freezing mark, 0°C (32°F), the temperature range in winter falls from -30°C (-49°F) to -60°C (-76°F) with the warmer figure occurring near open waters. Our knowledge of how cold it can get in the Greenland winter is tempered by the lack measurements over a long record. Most of the coldest temperature measurements have been reported by scientific expeditions or multi-year research stations and remote sensors.

Winter temperatures in the Greenland northern interior generally fall below -50°C (-58°F) and have fallen below -60°C (-76°F). The coldest accepted measurement was -66°C (-86.8°F) at the Northice research station of a British expedition in the early 1950s. However, more recent recordings by a remote weather station at Klinck, Greenland operated by the Space and Engineering Center of the University of Wisconsin, Madison reported a low temperature of -69.4°C (-92.9°F) on 22 December 1991. Given the short record of measurements in the Greenland interior, it is highly likely that temperatures, which would challenge Siberian Russia for the distinction as the coldest place in the Northern Hemisphere, of below -70°C (-94°F) are possible.

For more on the world’s cold spots, I refer the reader to Christopher Burt’s Weather Extremes blog: “The Coldest Places on Earth” on Weather Underground from which much of the above data was extracted. His book Extreme Weather also contains added information on cold places. To order, see the listing below.

|

Now AvailableThe Field Guide to Natural Phenomena: |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

Now |

The BC Weather Book: |