|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| ||||||||||

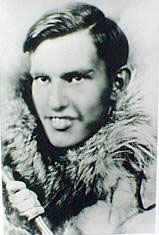

Paul Siple:

|

||||||||||

| "Vapor from a man's breath could freeze his eyelashes shut in an instant and make him believe he had gone blind. His breath would come in gasps and his joints would ache. The intense pain of the cold on fingers and toes could easily distract him, and even destroy his ability to reason clearly." Paul Siple |

It soon became obvious that the equation, often referred to as the Siple-Passel equation, could also be used to determine an equivalent temperature under a standard light-wind condition from actual readings of wind speed and temperature. This is the windchill temperature or windchill concept with which we are familiar today. The equation as the basis for the windchill remained unchanged until 2001, although the coefficients had been recalculated by several investigators to provide a better fit to the data and to accommodate other units of measure. As the Twentieth Century drew to a close, the Siple windchill concept was upgraded, and in the winter of 2001-02, replaced in regular winter weather reports in North America by a new formulation.

The third Byrd expedition returned home in the spring of 1941 as war spread around the world. Siple was met immediately by a representative of the United States Quartermaster Corps who explained to him that the government required his expertise on cold weather impacts on humans. Siple immediately went to work with the US government as a civilian scientist, but with the entry of America into the war in December 1941, he joined the armed forces, commissioned as an army Captain. During the war, he advised General Eisenhower and his generals on the best way to avert an epidemic of trench foot among the troops. In the spring of 1945, Lt Colonel Siple travelled to the Philippines to advise MacArthur, preparing plans to invade the main islands of Japan, on winter clothing requirements for the troops.

At the war's end, Siple joined the Army Chief of Staff's Office of Research and Development as a civilian scientist. This new job took him to the other end of the globe, the Arctic Basin, which had now swung high in the interest of national defence with the onset of the Cold War. Of this new focus he would write:

"My new career was to involve the application of my environmental research concepts to Army equipment and personnel in any environment they might be called upon to fight to preserve the free way of life. My interest was to broaden to the entire aspects of basic research and the segment with which I was a charter scientist eventually developed into the Army Research Office."

It wasn't long, however, before Siple would once again return to the Antarctic. Byrd convinced Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to undertake an enormous polar naval operation, officially titled The United States Navy Antarctic Developments Program, 1946-47 but better known as Operation Highjump. Siple was appointed as Scientific and Polar Advisor as well as serving as Senior Representative of the US War Department. The first step of Operation Highjump was to establish a tent city at Little America IV in the Bay of Whales, adjacent to the air strip built to handle the reconnaissance planes due to arrive. When the expedition returned to the United States in April 1947, much work of scientific and military importance had been accomplished at Little America IV and along the coastline of the continent.

For the remainder of his career, Siple continued working as Special Scientific Advisor with the Research and Development Office of the US Department of the Army. During his tenure, he received eight patents for the development of clothing, protective devices and building design. His research extended beyond the polar regions to encompassed desert, mountain and humid tropical conditions, but he still continued to lead the American presence in Antarctica through the 1950s.

But the call of the Antarctic was never out of ear shot. In the 1950s, an international movement to study the global environment proposed that the period 1957-58 be designated the International Geophysical Year (IGY). During the IGY, international research teams would focus on intense studies of the planet, particularly the upper atmosphere, the oceans and the polar regions. The Antarctic Ocean and continent were particularly prominent in the plans; the region held, after all, a mystique as the last truly unexplored regions on the Earth.

But the call of the Antarctic was never out of ear shot. In the 1950s, an international movement to study the global environment proposed that the period 1957-58 be designated the International Geophysical Year (IGY). During the IGY, international research teams would focus on intense studies of the planet, particularly the upper atmosphere, the oceans and the polar regions. The Antarctic Ocean and continent were particularly prominent in the plans; the region held, after all, a mystique as the last truly unexplored regions on the Earth.

Siple became a prominent player in the IGY planning and field programs associated with America's involvement. He accepted the position of Director of Scientific Projects for Operation Deepfreeze I, 1955-56 , arriving at McMurdo on December 18, 1955, his 47th birthday. On January 8, 1956, he undertook a flight to the South Pole with his old friend Admiral Byrd, the Officer in Charge of the US Antarctic Programme 1955-57, but to their disappointment, a landing was not feasible. As fate would have it, it was Byrd's last flight over the pole. He died March 12, 1957.

The major United States' role was to establish scientific research stations in Marie Byrd Land (Byrd Station), on the Filchner Ice Shelf (Ellsworth Station) and on the Clark Peninsula (Wilkes Station). Suggestions even came to construct and man a station at Latitude 90 degrees South, the South Pole. To many's surprise, South Pole Station was given the go-ahead under Operation Deepfreeze II 1956-57. For the research venture to succeed, support bases had to be built at McMurdo Sound, to support South Pole Station, and at Little America V, near the site of the former Little America(s) to provide support for the building of Byrd Station.

Prior to Operation Deepfreeze II 1956-57, Siple had not considered a return to the continent himself, let alone spending another winter there. He had become displeased with the administrative direction American involvement in the Antarctic had taken and also wanted to spend time with his family. Siple tried to deflect requests to take the scientific leadership for the South Pole, but found the call from Admiral Byrd impossible to refuse.

October 1956 again found him on the southern ice. Towards the month's end, Siple found himself aboard the first US Air Force plane to fly over the South Pole. This completed an interesting achievement. His friend and mentor Byrd had been the first to fly over both geographic poles. Siple's trip gave him the distinction of having been aboard the first US Air Force planes to fly over both the geographic poles, having been on the first USAF crew to cross the North Pole on October 16, 1946. (That mission was also the first to ever cross during the arctic night.)

On November 20, 1956, an advance construction party flew to the polar plateau site to begin erection of Pole Station, Antarctica, although Siple, Chief of the scientific staff, was not permitted to join them until November 30. A flotilla of support aircraft dropped tonnes of materials, supplies and equipment to construct shelters, a power station and scientific workshops, and to make the Pole Station self-sufficient for isolation during the long, dark winter.

By the end of the austral summer, March 1947, the station was completed and ready for overwintering. The construction crew was flown out and an eighteen-man scientific team flown in to become the first humans to spend winter at the South Pole. In the depths of the austral winter at Pole Station, the temperature dropped to an astonishing -77.2 oC (minus 107 oF) on September 18, 1957, the coldest temperature ever recorded on Earth at the time.

In late 1957, after exactly one year since his arrival at Pole Station, Antarctica, Siple prepared to leave. With a silent prayer and a last look at the polar plateau, Siple entered his plane with a one-way ticket to Christchurch, New Zealand via McMurdo. Thus ended an historic twelve months. For the first time, men (eighteen in number) had witnessed both the sunset and sunrise on the South Polar Plateau. The achievement of the expedition to construct the station was well recognized back home. On the front cover of its December 31, 1956 issue, Time magazine placed the image of Paul Siple, leader of Pole Station, Antarctica and featured the story of the expedition's work.

On March 28, 1958, five months after his triumphant return to the US, Siple received the National Geographic Society's prestigious Hubbard Medal for his many accomplishments on the Southern Continent. The following year his book 90 Degrees South, an autobiography as well as his accounts of time spent at the South Pole, appeared in bookstore windows.

Siple continued to work at the Army Research Office and from 1963-66 served as the first US Scientific Attache to Australia and New Zealand. A partial paralytic stroke in June 1966 forced him to return to the United States. But, despite the challenges left him by the stroke, requiring a sling for his paralysed left arm and a four-legged crutch for walking, Siple continued to work with the Army until November 25, 1968 when he sustained a fatal heart attack while seated at his desk. Paul Siple was only 59 years of age.

Siple continued to work at the Army Research Office and from 1963-66 served as the first US Scientific Attache to Australia and New Zealand. A partial paralytic stroke in June 1966 forced him to return to the United States. But, despite the challenges left him by the stroke, requiring a sling for his paralysed left arm and a four-legged crutch for walking, Siple continued to work with the Army until November 25, 1968 when he sustained a fatal heart attack while seated at his desk. Paul Siple was only 59 years of age.

In the annals of American Antarctica exploration, Paul A. Siple will long be remembered as a pioneer, in the same breath as his old friend Richard Byrd. In addition to the geographical features named after him, the United States in 1969 constructed a scientific installation at 76°S, 84' W in Ellsworth Land and named it Siple Station in his honour. More recently, a ceremony took place in Wellington, New Zealand on June 21, 1993 to rededicate the Admiral Richard E. Byrd Memorial. Added to its foot was a plaque honouring Paul Siple's Antarctic accomplishments and close relationship with Byrd.

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now |

The BC Weather Book: |