Weather Almanac for November 2006

FITZROY OF THE WEATHER SERVICE

Most people remember the name Robert FitzRoy primarily as a footnote to history: the captain of HMS Beagle, the ship that carried a young naturalist named Charles Darwin. Though at the time FitzRoy was the greater light, that dimmed in relation to his naturalist over time. This is unfortunate because FitzRoy was an master sea captain, an accurate surveyor and scientific observer, a visionary and a man of compassion. Most people remember the name Robert FitzRoy primarily as a footnote to history: the captain of HMS Beagle, the ship that carried a young naturalist named Charles Darwin. Though at the time FitzRoy was the greater light, that dimmed in relation to his naturalist over time. This is unfortunate because FitzRoy was an master sea captain, an accurate surveyor and scientific observer, a visionary and a man of compassion.

This view of Admiral FitzRoy is unfortunate for he deserves a prominent place in the pantheon of bright lights in the meteorological community. In British meteorological circles, he is known as the "grandfather of the weather service" having prepared and issued the first marine storm warnings. And that is the story I will tell here, though FitzRoy's story is more deep and wide. Elsewhere on this website (See FitzRoy: The Rest of the Story) I highlight events in his life not directly meteorological. For a full account, read the excellent biography FitzRoy by John Gribbin and Mary Gribbin.

The Early Years

Robert FitzRoy entered the world with impressive and noble blood lines, tracing his line back to an illegitimate son born of King Charles II and Barbara Villiers in 1663. (The name FitzRoy, according to the Gribbins, is a traditional one bestowed on acknowledged illegitimate sons of the King.) Robert's ancestor was the first Duke of Grafton and an able naval man who was Admiral on his royal father's ship the Grafton.

Robert FitzRoy was born at the family estate Ampton Hall near Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk on 5 July 1805. When he was but 12, Robert entered the Royal Naval College, Portsmouth. The following year 1818, he entered the Royal Navy. FitzRoy showed his intelligence by completing his course with distinction, then achieved a perfect score on his naval examination, the first to do so. Robert FitzRoy was promoted to lieutenant on 7 September 1824, at the age of 19 and served aboard the frigate HMS Thetis. In 1828 Robert FitzRoy was appointed flag lieutenant to Rear-Admiral Sir Robert Waller Otway, aboard HMS Ganges.

While serving Otway in Rio de Janeiro, FitzRoy received his first command, and one with several ironic foreshadowings of FitzRoy's future. HMS Beagle, under the command of Captain Pringle Stokes and HMS Adventure, under Captain Philip Parker King had been conducting a hydrographic survey of Tierra del Fuego. Off the South American coast, Stokes became morbidly depressed and shot himself. When Beagle returned to Rio, Otway appointed FitzRoy the Beagle's temporary captain on 15 December 1828 in order to complete the survey of Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia.

All able seamen, especially those in command positions, come to understand the power and danger of heavy weather at sea. When FitzRoy assumed command of Beagle he was 23 years old and still had much to learn. One weather incident that occurred shortly after he took command of Beagle imprinted on FitzRoy's mind, as he would later remark in The Weather Book. Off the South American coast, Beagle and Adventure encountered a pampero, the southern equivalent of the North American norther, a squally wind associated with a strong temperature drop. The Beagle was a ten-gun brig known in the Royal Navy as "coffins" for their reputation to "turn turtle" in heavy weather. Under the fierce pampero, Beagle nearly capsized and was in danger of hitting the rocks. Worse yet, two men were blown overboard and drowned. (During the second voyage of the Beagle, FitzRoy would lose only five men over five years and one of those was attributed to old age.) FitzRoy had underestimated the impact of storms, a lesson that would stay with him for the remainder if this life.

Following the successful return of the Beagle to England, FitzRoy's extraordinary survey work caught the eye of Francis Beaufort, then Hydrographer to the Admiralty — the same Beaufort whose name lives on in the Beaufort wind scale. (For a biography of Sir Admiral Beaufort, click here.) FitzRoy had intended a trip to Tierra del Fuego to return five Fuegans he had brought back on the Beagle. Unable to find a posting on a Royal Navy ship headed to Cape Horn, he requested a leave of absence to take a chartered vessel. When Beaufort heard of this, he, and FitzRoy's influential uncle the current Duke of Grafton, persuaded the Admiralty to again appoint Robert FitzRoy as captain of the Beagle and send it for a second voyage of survey and discovery to South America.

HMS Beagle, Straits of Magellan

from Voyage of the Beagle, by Charles Darwin

The Beagle

Robert FitzRoy spared no expense in fitting out the Beagle for this voyage. The ship was nearly rebuilt to fit his specification outfitted with the latest marine technology, including "lightning conductors," i.e., lightning rods. The accounts of the "Voyage of the Beagle" have been provided in Darwin's first great book which still remains in print, FitzRoy's massive report, and many other publications and web pages, and I won't dwell on the details here. But several aspects of the voyage relate directly to meteorology.

The Beagle was a very well outfitted vessel for scientific exploration. It carried several theodolites and chronometers and various types of barometers include a storm glass, a type of chemical sensor whose supersaturated liquid supposedly changed appearance with weather changes. FitzRoy intended to determine which type proved most useful and rugged for shipboard conditions. At the request of Beaufort, FitzRoy would employ Beaufort's wind scale in making wind observations during the voyage. He may also have used Beaufort's weather notation coding but I cannot confirm or deny this. (Any help from readers would be appreciated.)

FitzRoy and the Weather

In 1851 FitzRoy was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, supported by 13 Fellows including his old friends Francis Beaufort and Charles Darwin, for several of his achievements during and after the Beagle voyages.

At the time, a growing interest in weather sciences, or meteorology, was growing in many countries, and many scientists, led by American Matthew Fontaine Maury, felt much could be gleaned from sharing of weather observations. In Britain, James Glaisher had been appointed their first full-time government meteorologist as Superintendent of the Magnetic and Meteorological Department at the Greenwich Observatory. He also helped establish the British Meteorological Society in 1850.

FitzRoy had shown a great knowledge and insight on weather at sea, gleaned from his years as a captain. Early in 1854, he wrote a memorandum detailing how a proposal put forward by Maury for international cooperation in collecting weather information could be carried out. In that memorandum, he referred to the preparation of charts which would give "a synoptic view" of the weather, coining the term synoptic.

During the summer of 1854, the President of the Royal Society Lord John Wrottesley recommended that Robert FitzRoy be appointed chief of a newly formed department to undertake the collection of weather data at sea. On 1 August, FitzRoy began his work as Meteorological Statist (now we would say Statistician) to the Board of Trade. The department consisting of himself and three others would undertake the task of gathering weather data collected at sea and analysing them.

FitzRoy's department agents located ships' captains willing to undertake the gathering of weather observations while at sea and supplied the ships with a set of instruments that had been tested for standardization at the Kew Observatory. By May 1855, fifty merchant ships and thirty Royal naval vessels had been outfitted with the required instruments.

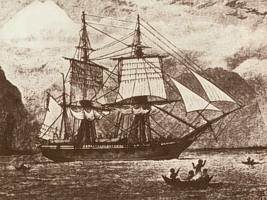

While waiting for the observational data to come in, FitzRoy devised an improved system for recording and displaying the weather data. FitzRoy called these diagrams wind stars — we would term them a form of wind rose today. The wind values were scaled proportionately to produce radial lines for each of the sixteen point compass directions. Connecting the ends of these radials produced a polygon showing the wind distribution around the compass. The Board of Trade Wind Charts covered a ten-degree square of ocean and contained weather information for the given quarter of the year to which they pertained: January–March; April–June; July–September; October–December.

FitzRoy’s presentation of the distribution of wind directions for the summer months.

The ‘stars’ show the distribution of winds and

the size of the circles the relative proportions of calms.

The dotted lines show the Cape Verde Islands and the African coast.

From first edition of the Wind Charts (August 1855)

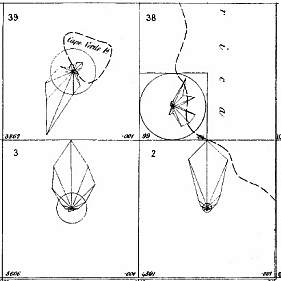

He also worked on development of a barometer that was rugged, reliable and simple. These were eventually distributed to every British port so that it could be consulted by seamen before embarkation. Many of these stone huts housing these mercury barometers are still visible in many fishing harbours. He also prepared a 50-page manual in 1858 with forecasting rules based on the barometer's behaviour. Some of the short forecasting rules found in the manual remind us of well-known weather lore rhymes. He also worked on development of a barometer that was rugged, reliable and simple. These were eventually distributed to every British port so that it could be consulted by seamen before embarkation. Many of these stone huts housing these mercury barometers are still visible in many fishing harbours. He also prepared a 50-page manual in 1858 with forecasting rules based on the barometer's behaviour. Some of the short forecasting rules found in the manual remind us of well-known weather lore rhymes.

Thus,

"Long foretold, long last;

Short notice, soon past."

becomes

"It may be repeated that the longer a change in wind or weather be foretold before it takes place, the longer the presaged weather will last; and, conversely, the shorter the warning, the less time whatever caused the warning, whether wind or a fall of rain or snow, will continue."

And,

"First rise after low

Foretells a stronger blow."

becomes

"The most dangerous shifts of wind, or the heaviest Northerly gales, happen soon after the barometer first rises from a very low point, or if the wind veers gradually, at some time afterwards, though with a rising glass."

FitzRoy has been associated with several versions of the barometer over the years including the "storm barometer" that uses changes in the liquid within to foretell the weather and that now bares his name: the FitzRoy Storm Glass.

The invention and improvement of the telegraph during the 1830-40 period sparked the science of weather analysis in a way perhaps not equalled until the launching of weather satellites. Using the telegraph, weather observations from far-distant locations could be collected in the matter of hours and plotted on a map to give a snapshot of current weather conditions, what we today call a synoptic weather chart. Joseph Henry had begun such a network in the United States in 1847, and James Glaiser had been commissioned in London by the Daily News to collect weather data from around Britain. His series of text weather reports the "Daily Weather Report" began on 31 August 1848. In 1851, he produced and displayed the first British weather maps.

FitzRoy was among the first to understand that weather in the middle latitudes moved generally from west to east, and although his mandate was to look only at conditions at sea, he began to broaden his interests to weather over the land as well. He theorized that if weather occurred with some degree of regularity, perhaps he could use barometric pressure observations over land to give an indication of weather at sea, at least over coastal waters. By constructing weather charts, which he coined synoptic charts because they showed a synopsis of weather at the same time over a wide area, he could find recurrent patterns that foretold of hazardous conditions at sea and thus could be used to give warnings of dangerous weather to mariners.

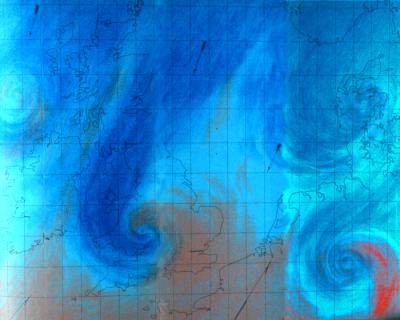

Tropical and Polar Air Currents.

Plate VII, The Weather Book: A Manual of Practical Meteorology,

by Rear Admiral Robert Fitzroy 1863.

Courtesy NOAA Treasures of the NOAA Library Collection, US Dept of Commerce

The concepts that were fermenting in FitzRoy's mind foresaw the need for and the ability to forecast weather, particularly storm events. Then an event that would allow FitzRoy the further development of these concepts occurred in October of 1859. A major storm moved across Britain and nearby seas causing much damage to shipping. Among the many vessels lost was the Royal Charter with over 450 lives (for details of the storm see last month's "Weather Almanac: The Royal Charter Storm.")

FitzRoy was convinced that the disaster may have been averted or lessened had warnings been issued in time for these ships to take shelter. He proclaimed such in a paper to the British Association in 1860. With similar findings from the official inquiry into the Royal Charter sinking, FitzRoy received formal permission in June 1860 to begin a storm warming system to shipping. By September he had placed 18 weather stations with barometers and other weather instruments at various locations around the British Isles and commissioned local telegraph operators to send the readings to London. The observations were standardized to be taken at 9 am (later moved to 8 am). He was also able to obtain daily observations from six sites on the Continent.

FitzRoy's first official storm warning was issued on 6 February 1861 and telegraphed to a number of shore stations. The first year, warnings went out to 50 locations, the following year 130 received the warnings. Though some vessels ignored the warnings in the beginning, the system proved successful and countless lives were saved over the years because of them.

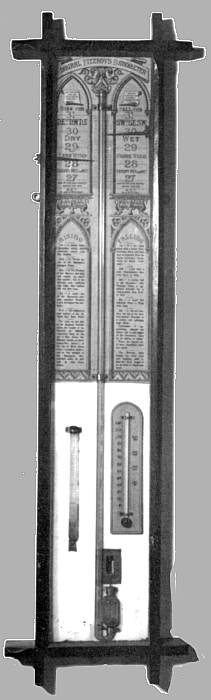

The warnings were posted by means of a set of signals that would be visible to those at sea: a cone and drum arrangement during the day and light arrangement at night. The cone and drum signalling apparatus consisted of a mast from 30-40 feet (9.1-12.2m) high upon which the cones, drums and signal lanterns were hosted. The cones and drums (a cylinder) were made of a canvas-covered wooden frame about three feet tall (0.91m). The advantage of these shapes was that they were recognizable from any viewing direction.

Daytime Storm Signal

from The Weather Book: A Manual of Practical Meteorology,

by Rear Admiral Robert Fitzroy 1863.

Courtesy NOAA Treasures of the NOAA Library Collection, US Dept of Commerce

When a cone was hoisted with its point upward, it indicated a gale from the north — "north cone flying" was the expression used — and if it pointed downward, a south gale was expected ("south cone flying"). The hoisting of the drum indicated storm conditions but an indefinite direction. A drum and cone together warned of a violent storm from the direction of the cone point.

Night Storm Signal

from The Weather Book :A Manual of Practical Meteorology,

by Rear Admiral Robert Fitzroy 1863.

Courtesy NOAA Treasures of the NOAA Library Collection, US Dept of Commerce

At night, three lights in a triangle pattern replaced the cone arrangement, with the triangle's point facing up for northern gale and down for south gale. A four-light arrangement in a square pattern replaced the drum.

But storm warnings were not all FitzRoy felt could be achieved with a study of the synoptic situation. He saw the possibility of general weather forecasting. In fact, FitzRoy is credited with coining the term forecast to distance the product from prophesies and foretellings that had astrological, religious, or sorcery roots. (The US forecasts used the term probabilities at this early stage.)

To do so meant an upgrade and expansion in the weather observation network to include inland sites, an increase in staff, and, of course, a higher budget. The pace in the "forecast office" must have been frantic. According to FitzRoy's own accounts, the forecasts, for not only the next 24 hours but the following day as well, were supposed to leave the office an hour after the raw data had been received!

Here is how the procedure unfolded. Observers collected readings of temperature, pressure, humidity, wind conditions at ground and at higher altitudes (assessed from cloud movements), sea state, amount and type of precipitation, and how these had changed since the last observation. At 8 am these data were forwarded via telegraph to London and by 10 am received at the Parliament Street meteorological office. The raw data were read, checked for obvious errors and adjusted where needed. The data were then written on special forms and passed to the department Chief or his assistant with the original telegrams. The day's forecast was prepared and written out. These initial forecasts were copied and sent at 11 am to the Times, Lloyd's of London, the Shipping Gazette, the Admiralty, the Board of Trade, the House Guards and the Humane Society(?!). Later they were sent to other afternoon newspapers and with some modification from later observation reports, to the morning papers for the next day's editions.

Since there was a time lag between the initial forecast and the information reaching those via the newspapers in distant towns, FitzRoy felt that a forecast for a second day was required since many might only see the first day forecast after the fact. Perhaps here, FitzRoy was stretching the art of weather forecasting for his time. This second forecast would eventually lead to much criticism for bad forecasts in the coming years.

In his spare time, FitzRoy also worked on a project dear to him: the writing of a compendium of the state of the art of meteorology and his ideas on weather forecasting written for a lay audience. The Weather Book, which he told a friend took four months to write, was first published in 1862, with a second addition in 1863. The title, he explained, was simple so as not to scare away potential readers: "This popular work is intended for many, rather than for few, with an earnest hope of its utility in daily life." The book began with a phrase used by writers of weather books frequently in the next century and a half: we all live in "an ocean of air," a fitting analogy for a naval man. The Weather Book ran 340 pages of text with sixteen maps and diagrams and over a hundred appendices and sold for fifteen shillings. And its diagrams have an uncanny similarity to modern satellite images. FitzRoy sold the copyright (the practice at the time) for Ł200.

While much has been learned in the nearly 150 years since its publication, the book shows, according to the Gribbins, how much FitzRoy had correctly understood about the workings of the atmosphere. He also saw that more was needed than just the collection and analysis of data. "Until lately, meteorology had been too statistical in practice to afford much benefit of an immediate and general kind." Ships' captains, he wrote, "should be able to differentiate between cyclones and storms accompanied by veering winds."

As The Weather Book reached its pinnacle of interest and the public regularly read FitzRoy's forecasts, he received notice of his promotion to Vice Admiral. (Promotions were based on seniority and death of others rather than achievement.) But as often happened in FitzRoy's later life, ascents to peaks were followed by falls. His forecasts and their science were criticized, the former mostly for its accuracy but by some for economic reasons, including those who wished to profit by the issuance of forecasts. Some shipowners cried over lost revenues when ships stated safe in harbour during stormy weather, never considering the cost of a lost ship.

Even the Times which ran his forecasts took jabs at the product (the burden of all forecasters): "During the last week Nature seems to have taken special pleasure in confounding the conjectures of science." The piece continued that this was not the fault of the laws of nature, but that "Accurate interpretation is the real deficiency."

A perfectionist and workaholic, FitzRoy surely took criticisms such as that last quoted line personally. Concurrent with the criticism of FitzRoy's meteorological work, another issue would take its personal toll, and that arose from the theory of evolution proposed by his Beagle companion Charles Darwin (see An Unfortunate End). The upshot of all this stress was that his health began to suffer. Not yet sixty, he was aging rapidly and likely in a bad mental state.

Following FitzRoy's death in 1865, the work of the Meteorological Office, which would later split from the Board of Trade and become the British Meteorological Office, came into dispute. The accountants at the Board were not sure the forecasts provided sufficient value for the money. It was also charged that FitzRoy had exceeded his mandate. A Royal Society inquiry admitted the storm warnings were "of some use" and had promise, but recommended that the Board cease the daily forecasts. The last, for a time, were issued on 28 March 1866.

The Man Remembered

His obituary shared space in The Gentleman's Magazine of June 1865 with that of Abraham Lincoln, and in it, a naval officer who had known him since his boyhood remarked:

"...a more high-principled officer, a more amiable man, or a person of more useful general attainments never walked a quarter-deck."

Sadly, FitzRoy faded from his rightful spot in British history following his death, remembered only as Darwin's Captain. He was one of the few of his family with outstanding achievements on many fronts to not have a noble title, not even a knighthood. FitzRoy was often neglected or overlooked for his meteorological work. Sir Napier Shaw in his landmark Manual of Meteorology, Volume I Meteorology in History only mentions FitzRoy's contributions briefly — for his list of weather "rules" to be used with barometric tendencies.

Recently, however, his fame has been revived, and the name and memory of Admiral Robert FitzRoy regain a more proper place in British life. The Meteorological Office that he essentially founded and nursed in its early years now has its headquarters located in Exeter on FitzRoy Road. Robert FitzRoy's pioneering work on marine storm warnings and for the Lifeboat Association which both promoted marine safety is now directly acknowledged every day in the Shipping Forecasts. In 2002, one area of the British sea area, formally Finisterre, for which marine forecasts are issued has been renamed FitzRoy.

Learn More From These Relevant Books

Chosen by The Weather Doctor

- Gribbin, John and Mary Gribbin: FitzRoy: The Remarkable Story of Darwin's Captain and the Invention of the Weather Forecast, 2004, Yale University Press, New Haven CT, ISBN: 0300103611, 352pp (hc).

- Darwin, Charles: The Voyage of the Beagle: Charles Darwin's Journal of Researches, Penguin Classics; Abridged Ed edition (1989).

- Mellersh, H.E.L. FitzRoy of the Beagle, 1968, order through Abebooks.com

Written by

Keith C. Heidorn, PhD, THE WEATHER DOCTOR,

November 1, 2006

The Weather Doctor's Weather Almanac FitzRoy of the Weather Service

©2006, Keith C. Heidorn, PhD. All Rights Reserved.

Correspondence may be sent via email to: see@islandnet.com.

For More Weather Doctor articles, go to our Site Map.

I have recently added many of my lifetime collection of photographs and art works to an on-line shop where you can purchase notecards, posters, and greeting cards, etc. of my best images.

Home |

Welcome |

What's New |

Site Map |

Glossary |

Weather Doctor Amazon Store |

Book Store |

Accolades |

Email Us

|

|