|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||

Weather Almanac for January 2006THE FLAVOUR OF LOWSThe ice cream franchise Ben and Jerry's has creatively named its frozen treats for many years such as Tennessee Mud and Cool Britannia. I have always wondered if they had any named after weather. Tornado Swirl and Cirrus Ice would seem good flavors. You see, there are many different flavours of weather out there, and some of them are frozen. So for this cold month of January across most of North America, I have decided to look at the flavours of one particular type of weather: the Low pressure system. A few years ago, I posted an article on low pressure systems in general (The Highs and Lows of Weather: Part 2 — The Low). But often in our daily media weather reports we hear terms such as tropical lows, extratropical lows, polar lows, and thermal lows. And fairly often these days, the lows are given more fanciful names: Nor'easter, Colorado Low, Alberta Clipper, Tropical Storm Delta, Hurricane Wilma, Witch of November. Before we get started with the particulars, let's review what a surface Low or low pressure cell is. (I will capitalized Low here to distinguish between an organized region of Low pressure and low pressure in general.) A Low is characterized by (1) converging air flow at the surface; (2) ascending air currents at its core where the converging currents meet; and (3) regions of divergent air flow above the region where the air currents flow away from the rising core. When the combination of these processes removes air faster from the surface than it can be replaced by the inflow of surface air, a temporary mass deficit in the air column lowers its weight, and thereby reducing its surface pressure. (Pressure is defined as a force acting on a unit area, and weight is a force deriving from mass and gravity.)

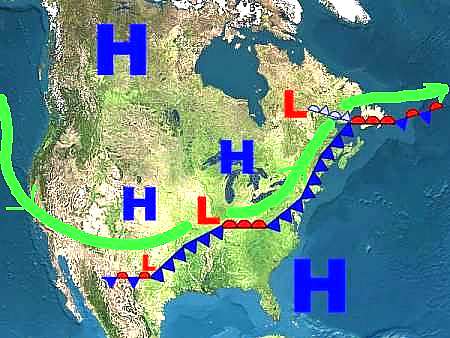

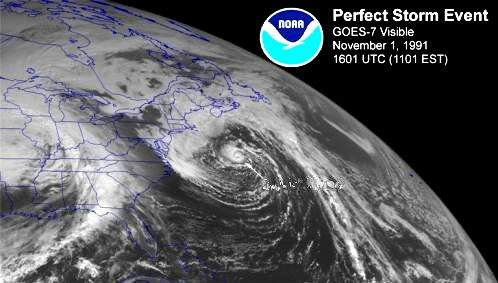

When a pressure gradient develops in the region outside the low pressure centre, winds will flow from high to low pressure. Away from the tropics, the Coriolis force causes the winds to flow around the Low in a counterclockwise manner in the Northern Hemisphere (clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere), a condition meteorologists term cyclonic. Hence the more technical alternate name for a Low pressure cell: cyclone.  Meteorologists generally distinguish five main flavours for Lows: Tropical Lows, Extratropical Lows, Subtropical Lows, Polar Lows and Thermal Lows. In part, the qualifying adjective — excluding the last one on the list — describes where geographically the Low has formed: the tropics, mid-latitudes, subtropics, or polar regions, respectively. However, there are important differences in their structure and method of formation which distinguishes them from each other. Thermal Lows generally have preferred regions of formation as well, but these can vary from the subtropical to the mid-latitudes. Tropical Lows are born over the warm waters and land masses in the equatorial zone north and south of the Equator. To form a low pressure system with spiralling winds, the Low must be at least a dozen or so degrees away from the Equator itself, but a general region of low pressure, known as the intertropical convergence zone, is a permanent feature of the atmosphere around the Equator.  In the tropics when a region of intense thunderstorms builds over the warm surface below, conditions are ripe for forming a tropical Low. With surface convergence and light winds aloft, the thunderstorms can organize into a rotating system that slowly spins away from the tropics. Such tropical lows may become the juvenile stage for tropical storms and hurricanes/typhoons, or may live a short, stormy life before fading away. Heat released as water vapour condensing to form clouds is the major source of their energy. Tropical Lows are sometimes called warm-core systems because they form due to warm air rising off the surface with no help from cold air; tropical Lows do not have fronts. Once such tropical storms move off warmer surface waters and over land or colder waters, their sustaining heat source is cut off and they begin to lose strength. Extratropical Lows, aka mid-latitude Lows, are the most familiar lows to those of us living in the middle latitudes, from about 37 to 60 degrees of latitude, North and South. These Lows form predominantly in the vicinity of the Polar Front, a hemispheric boundary region that separates subtropical air from polar air. In this tempestuous zone the cold, drier air of the polar regions collides with the moist, warm air of the subtropics.  As the frontal boundary separating these airs begins to turn and twist, the twist often becomes a swirl and the swirl, a closed low pressure region. Extratropical Lows may remain along the Polar Front showing the characteristic warm-front/cold-front wedge as a member of a cyclone family or break away to live a singular life. Since cold air is important in the formation of these Lows, they are called cold-core systems. Extratropical Lows can live for many days and move across oceans and continents. They can be small in size, a few hundred kilometres (miles) in diameter, or sprawl over a thousand kilometres. Precipitation may be of any form and can range from a brief shower to multi-day downpours. Certain areas of the globe harbour favoured spawning grounds for extratropical Lows. In the Northern Hemisphere, the two most prolific producers of Lows are the semi-permanent Aleutian or Alaskan Low in the Gulf of Alaska and the Icelandic Low off Iceland. During the winter, the Aleutian Low produces a steady train of Low pressure systems that spin up in the relatively warm waters of the North Pacific Ocean and race to a collision with the North American continent from Northern California to British Columbia and the Alaskan Panhandle. The result of this clash are prodigious precipitation events where rainfalls can reach the depths of snowfalls elsewhere. From these frequent and heavy rains, the great Pacific temperate rainforest emerges. Subtropical Lows may exhibit characteristics of their tropical and extratropical cousins and often form through a melding of two such Lows. The infamous Perfect Storm of 1991 arose when a strong extratropical Low merged with the remnants of Hurricane Grace off the American Atlantic Coast.  Polar Lows, small, shallow cyclones, mainly form in winter over the open waters of high-latitude seas within a polar or arctic air mass. They are spawned by the contrast between the cold air above a relatively warmer sea surface below. The warm air rising from the sea starts the convection/convergence process going. Polar Lows can generate gale-force winds or higher winds in their extreme. Typically, polar Lows live between 12 to 36 hours and are of smaller scale than their non-polar cousins. Polar Lows are small in size; their width varies between 100 to 500 km (60 and 300 miles). Polar Lows have been the topic of discussion of many mariners in Northern waters for centuries, but only with the advent of polar satellites was their existence verified. Polar Lows develop in the relatively warm, ice-free waters in the Nordic Seas, the Labrador Sea, the Gulf of Alaska and the Sea of Japan, but they are also common over the polar waters surrounding Antarctica. The clouds associated with polar Lows have a unique formation that stands out on satellite imagery. During their development phase, these Lows first show a typical comma cloud feature. When mature, the most prominent features of a polar Low are spiral cloud bands and often a clear central eye within the cloud vortex . Polar Lows have been termed polar hurricanes, in part because they have some similarity in structure to tropical storms such as spiral-shaped cloud pattern and a cloud-free eye. Like tropical storms, polar Lows lose much of their energy when they move over land away from the warm waters and rapidly weaken. Polar Lows are capable of causing blizzard conditions over land. Some polar Lows have well-defined fronts like those associated with mid-latitude cyclones.

A NOAA-9 polar orbiter satellite image (visible band) |

|||||||||

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now |

The BC Weather Book: |