|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||

Weather Almanac for October 2001FIRST FROST

Even when accurately predicted by forecasters or one's own reading of weather signs, first frost is always a shock, and its arrival a time of captivating beauty tinged with sadness. Waking to see frost glistening on the pumpkin or rooftop is a significant autumnal event, melding the simple beauty of white with the bright colours of turned leaves. Although first frost is often not a killer (except for sensitive plants), it is a harbinger of what awaits in the weeks ahead. By October's end, Jack Frost will have visited nearly all of Canada and much of the United States, his hoary finger ending the growing season for much of the northern continent as he heralds the southward meandering of infant winter. When Jack's first chilling tickle may occur, however, can be anytime from early August to late October, even delaying into November, depending on location, local conditions and the quirks of the current weather regimes.  First frost can be either of two characters: the first slides or rushes in, often descending from above; the other rises from the ground, creeping in on still nights. We who study the weather call them advection frost and radiation frost, respectively.

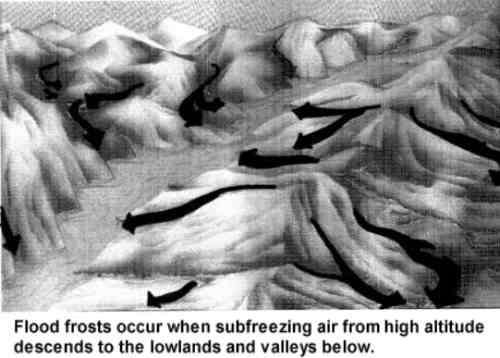

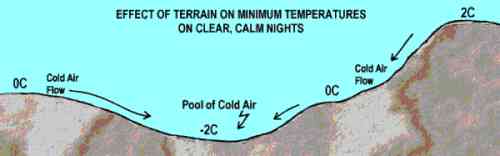

Close cousins to the frost mass are the descending flood frosts most common in hilly terrain. Whereas frost masses move across continents under the push of global air currents, flood frosts fall downslope under the pull of gravity -- their cold air heavier than the surface air undercutting the lighter, warmer air below. Flood frosts form at high elevation and flood down hillsides and valleys, forming frigid pools in depressions and low terrain. Unlike the frost masses, flood frosts usually whisper as they roll down the hills and valleys at night, stirring dead leaves in passing and blackening low-lying vegetation with their touch.  Flood frost is a form of atmospheric motion known as katabatic flow. These cold, dense gravity currents usually flow on the small, local scale (meso- or micro-scale flows) although the katabatic winds of the Antarctic may be regional in scale. In many places, katabatic winds are significant enough to earn their own names: Sno in Scandinavia; Surazos in Peru; and the Mistral and Bora of Europe's Alps.  When flood frosts descend, they nip first at the grasses and other ground-hugging vegetation, but as the cold wedge thickens, bushes, shrubs and trees may feel the heavy hand of frost. If the flow is short and swift, and the frosty air pools in a valley bottom or depressed hollow, a flood frost may leave a "bathtub ring" of white or black at a common elevation, frosting all below and sparing all above. Radiation frost, in contrast, comes on silent nights. It needs clear, dry air above the ground, a cool surface air temperature at sunset and light regional winds. It loves to return in Autumn when nights are again long and cooling can continue without the deterrence of solar energy for many hours.  Radiation frost, in fact, is the true mother of both frost masses and flood frosts. In the former, it chills the stagnant air mass through the long polar nights until the mass is so cold and heavy that it begins to slip southward. In the latter case, radiational cooling feeds the flood by chilling air at high, exposed locations to subfreezing temperatures which then descend the topography. Radiation frost is a consequence of the surface radiation balance. The planetary surface receives heat radiation from the sun and sky, and clouds if present. The surface then uses some of this energy to heat itself and perhaps to evaporate water or melt ice, the rest is radiated back to the sky. During the day, the sun's energy is usually sufficient to heat the surface, or at least prevent the surface temperature from dropping. But at night, with the sun gone, the surface generally radiates heat away faster than the sky and clouds can replenish it. This is why surface temperatures usually drop when night descends and continue to do so until dawn. On a clear, dry night, the surface losses heat rapidly and receives little back from the cold sky. The number of hours of night and the sunset temperature determine whether the nighttime minimum temperature will be only cool or decidedly frosty. The likelihood of frost temperatures (those below the freezing temperature of water) near the surface further increases if regional winds are light because the cold air can remain in place and mixing with the warmer air above is inhibited.

...The rising of the morning sun above the tree tops threw a line of light across the lawn, erasing the frost that the night had written on the landscape. By noon, this first frost was forgotten, but its mark tattooed the vegetable garden, and the tomato plants no longer held their heads high. With the first hard frost behind us, we then look toward October's next surprise: the onset of Indian Summer. Be back in mid-month for thoughts on that unique little season. Learn More From These Relevant Books

|

|||||||||

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now |

The BC Weather Book: |