|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||

Weather Almanac for April 2001FROM SEA FROTH TO RAINDROPSThe convergence of several events forced the writing of this month's Almanac back in my list of priorities. When I finally found time to prepare it, the subject became elusive, none of the ideas I had scribbled down in the past quite jostled the muse to action.

The turning tide coupled with a few waves from a passing fishing boat roll a small shushing surf onto the shoreline, breaking in a banner of bubbles on the sand and beach pebble. Almost immediately, two thoughts pop into my head (one from each hemisphere?), and they have an interesting connection. One is the role breaking waves and particularly the bubbles formed in the process play in the formation of clouds and precipitation. The other is books, particularly my favorite weather books, an essay topic which had been in my mind as for on my favorite weather books, since reading an article by Ontario naturalist Van Waffle on classic nature writings that started me thinking. The two ideas have a common link as two of the books on my list of weather "classics" were written by Duncan Blanchard. The most recent The Snowflake Man is reviewed on this site. The other, and the linkage to breaking waves, is his 1966 book From Raindrops to Volcanoes that looked at his research work into the causes of precipitation and their link with the sea. Elsewhere on this site, I have stated that the two main ingredients for cloud and precipitation formation are water (vapour) and dust or some similar small particles, that serve as condensation nuclei for the water vapour. Sea salt particles are one major class of natural condensation nuclei and are not found only over the oceans of the world. Measurements of airborne particles show that sea salt particles can be found as far inland as the mid section of the continental US. In From Raindrops to Volcanoes, Blanchard tells us how these particles leave the sea surface to make their way into clouds and rain. I will try to summarize the process in as lucid a way as Blanchard has. (His detailed story of science and discovery covers more pages of the book than this account has paragraphs, and any shortcomings herein are mine alone.) If you can find a copy of From Raindrops to Volcanoes in the library or a used bookstore, I urge you to read the detailed account. It is one of the most fascinating stories of meteorological discovery I have read. As the waves break on the shoreline before me, I can see bubbles forming, frothing up the surf and giving it that tell-tale hiss. This is not, however, the only process by which bubbles form before breaking on the water surface. Chemical and biological processes within the water volume can generate gas bubbles that rise to the surface. Another mechanism is the impact of precipitation falling on the sea surface, both raindrops and snowflakes. (We may not think about snowflakes forming bubbles when they strike a water surface, but Alfred Woodcock, who worked with Blanchard at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, found them to be very effective bubble producers.)

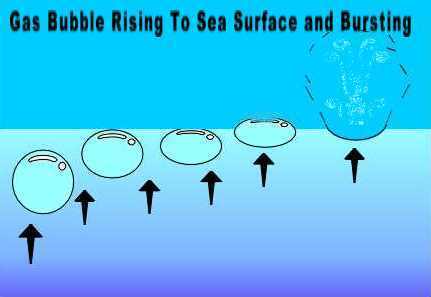

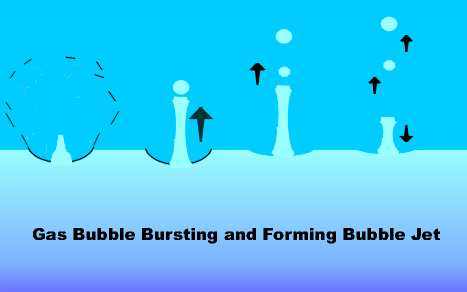

The main producer of sea bubbles, however, is the wind. Whenever the wind speed exceeds 11 km/h (7 mph), the wind interacts with wave crests to form frothy whitecaps. Any patch of frothy sea surface contains hundreds to hundreds of thousands of individual bubbles of many sizes, all about to break. Let us look more closely at this chaotic picture, focusing our attention on just one of the many bubbles. In whatever manner it is formed, a sea-surface bubble is a very small volume of gas -- usually air -- surrounded by sea water. Most are less than 0.5 mm (0.2 inches) in diameter. If we assume our bubble formed far enough below the surface it will form a spherical volume of gas, whose shape results from the outward pressure of the gas being balanced by the hydrostatic pressure of the surrounding sea water pushing uniformly inward on the bubble. Since the bubble gas is less dense than the surrounding sea water, buoyant forces act to push it upward toward the surface.  When the bubble reaches the surface, the combination of buoyant forces and momentum push against the top surface layer of water molecules that isolate the bubble air from the atmosphere. Eventually, the surface tension of the water surface is no longer sufficient to hold the gas in. At this instant, the bubble ruptures, bursts, pops. The surface film that had formed the upper bubble boundary explodes upward, spreading like shrapnel into the air above. For an instant, the sea surface has a dimple, a depression, a cavity where the bubble had been below the sea boundary prior to bursting.  With the sudden release of the pressure exerted by the bubble gas on the surrounding sea, the water rushes in to fill the depression in the surface. In closing the cavity, a small vertical column of water with a wide base -- shaped in the words of Blanchard "like a miniature Eiffel Tower" -- rapidly extends up from the bottom of the collapsing bubble volume. Researchers have called this feature the bubble jet. [Its existence was hypothesized by several investigators studying bubbles in the first half of the 20th Century, but the whole process is so swift -- taking but a few milliseconds -- that none could be sure of the exact details of their observations. Then in 1953, Charles Kientzler, also working at Woods Hole, used a high-speed movie camera and a still camera with high speed flash to obtain photomicrographs of the process and confirmed much of what had been conjectured.] As the bubble jet itself collapses back into the sea, it ejects up to five small droplets that have been pinched off the jet column into the air above. If you have ever felt the tickle on your lips when drinking a fizzy carbonated beverage, then you have felt these jet droplets. And you can easily see them by looking closely over the surface of the carbonated beverage in a glass. Now we are reaching the heart of our story. Those bubble jet droplets (as well as the "shrapnel" of the surface film during the initial bubble break) ejected from the sea surface may fall back into the sea, forming additional bubbles in the process. But many are caught in the turbulent wind field at the sea surface and lofted up and away from the waters below. Charles Keith, another member of the Woods Hole research team, determined that bursting bubbles on the sea surface could eject the initial jet droplet as high as 18 cm (7 inches) above the surface. Some eventually return to the sea, but other are caught in the wind field updrafts to travel great distances. Before I comment on the travel options for our vagabond droplets, I want to take a closer look at their composition. Obviously, the jet droplets in this case are composed of sea water, generally from the uppermost layer of the sea. Their composition includes water (naturally), a wide variety of sea salts, some organic compounds and a number of microorganisms -- bacteria, viruses, plants, animals -- specific to the water body from which the droplet issued. Although the life forms riding the droplet provides a fascinating story of their own, I am most interested here in the sea salts dissolved in the water. Sea salts comprise a wide catalogue of inorganic and some organic compounds, but most of the mass is sodium chloride (table salt) and salts formed from sodium, magnesium, calcium and potassium combined with chloride and sulphate. Those riding the droplets high into the air can be pushed across the waters as sea spray to impact on ships and oil rigs at sea, or inland along the coast forming what coastal ecologists call the spray zone. The longer the salty droplets remain aloft, the greater the likelihood that most or all of their water will be evaporated away. When all the water evaporates, minute particles of pure salt are left suspended in the air. Being quite small, they are easily transported "thither and yon," up and down, with the vagaries of the turbulent wind. I live about 3-5 kilometres (2-3 miles) inland from the nearest shore of Vancouver Island and about 15 metres (50 ft) above sea level, yet even in the peak of our dry season, my windows become coated with a thin layer of wind-deposited salt. And a few kilometres is no long trip for many sea-born salt particles. Let me take you back to Island View Beach to conclude this story. As I watch the waves breaking gently over this eastern shore of the island, the winds are blowing gently from the west and are warm in temperature compared to conditions I would find over the open waters before me. The jet droplets formed in the froth of the breaking surf are caught in the turbulent wind field where wind, land and sea meet and many ride upward on the warm air. In my mental picture of the process, I see those minute jet droplets lofted above the cold water surface headed eastward toward the mountainous San Juan Islands. Many will have become salt aerosols (rather than salty water droplets) by the time they reach these islands where they will be lifted higher aloft as the winds ascend the slopes of the island summits.  Further east, I see the winds and their moist, salty air rising even higher as they are forced up and over the continental coastal mountain range. This part of the process I actually do see -- in the form of cumulus clouds building in the eastern sky. Somewhere over Washington State, millions of these salt particles will fall to earth, having gathered, along with other condensation nuclei, to form raindrops and snowflakes. But some will escape the deposition and ride the air currents ever eastward. Some may even survive the traverse of the western cordillera to be mixed into air masses descending from polar latitudes and caught in an Alberta Clipper or Colorado Low to form clouds and precipitation somewhere over North America. In a few days time, my Georgian sea salts may fall as rain or snow over my old stomping grounds of Illinois, Michigan, or Ontario. Nice to still remain in contact with them. A very lucky few may hitch a ride on just the right parcels of air and somehow escape the deposition process for quite a long time, wandering across the globe before finally coming to rest. I like to think a few will ride full circuit and return to Vancouver Island, falling in rain to the beach where I saw them off this April day. Learn More From These Relevant Books

|

|||||||||||

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now |

The BC Weather Book: |