|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Windmills: Turning In The WindOne of the inspirations for my May 2010 Weather Almanac on wind energy arose from my search for new and interesting subjects for my artwork. I have been interested in old structures, particularly old barns and related outbuildings, since my youth and often go back to Eric Sloane’s The Age of Barns for enjoyment. I love the textures of their surfaces, their patina, and how they fit into a weather scene.

The idea of writing about wind energy and windmills merged and I started the May Almanac intending to cover both in one piece. But the lure of windmills demanded a separate piece. Early Wind UsesHuman use of wind for generating power has been with us for millennia. The first device, according to many archeologists, which humans built to take advantage of the wind was the boat sail. I am inclined to think the first wind applications were architectural, devices designed to add in cooling or air-cleansing in a dwelling, but, of course, these are not power-generating devices.

The application of the sail concept to land-based usage seems to have taken longer to evolve. We have records of the Chinese mounting sails on land vehicles dating from the early 5th Century in the Book of the Golden Hall Master written by the Daoist scholar Xiao Yi, later Emperor Yuan of Liang. Xiao attributed a “wind-driven carriage” able to carry thirty passengers to the work of Gaocang Wushu. The First Windmills

The invention of the first windmill-like device appears to have arisen in Persia (modern Iran) sometime in the second half of the first millennium. It was described as a vertical-axis system used to pump water for irrigation. Some accounts attribute the windmills invention to China two millennia ago, but no accepted documentation of such an early date exists. The first detailed description (by the Persian geographer Estakhri in the 9th century) of a Persian windmill showed the six to twelve vertical sails, built from bundles of reeds or wood, attached the a central vertical shaft by struts. The vertical axis windmill is similar to a paddlewheel turned vertical with its sails surrounding a vertical shaft, which turns as the wind pushes the sails around the shaft. The vertical-axis windmill when used as a grindmill has the vertical shaft attached to the upper grindstone, which turns in the wind to grind the grain placed under it on a stationary stone. This technology spread from Persian through the Middle East into Central Asia and then to India and China. There appears to be some debate as to whether the vertical-axis windmill then moved into eastern Europe or independently originated there. The vertical-axis windmill in Europe was generally replaced by the horizontal-axis windmill in the early centuries of the Second Millennium. However, vertical-axis windmills can still be found in use, and some new wind-turbine power generators have adopted the vertical shaft design. An interesting side application of the vertical shaft design is the Tibetan Buddhist prayer wheel. Buddhist tradition considers the mechanical spinning of the prayer wheel to have a similar meritorious effect as oral recitation of the prayers in sending them out into the world. The Horizontal-Axis WindmillIn the early centuries of the Second Millennium, a new windmill design appeared in which the drive shaft’s axis of rotation was horizontal rather than vertical. These sails generally attach to the end of the shaft like a multi-bladed propeller or pinwheel. The initial reason for the change in design is unknown though some speculate it evolved from the design of the waterwheel (although they run on entirely different principles).

The first large applications of the horizontal axis windmill arose in northwestern Europe (northern France, eastern England and Flanders) during the last quarter of the 12th Century. The first documented reference to such a mill — in Weedley, Yorkshire — dated to 1185. The earliest known illustrations of these mills appeared in 1270. These early sunk-post mills ground cereal grains for flour. The sunk-post mill or postmill was so-named because it had a large, upright post on which the bladed shaft balanced. This design allowed the mill sails — the earliest design showed four sails — to be turned into the wind for maximum capture of the wind flow. The horizontally turning shaft had its rotating motion translated to vertical movement through a series of wooden cog- and ring-gears similar in design to the waterwheel of Vitruvius, a Roman writer, architect and engineer.

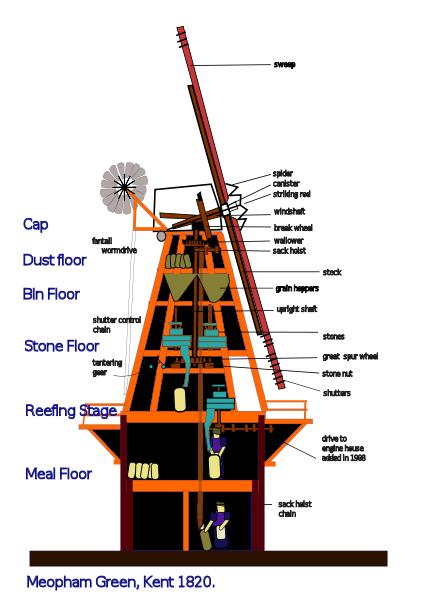

The next evolution of the windmill was the smock mill, so named for its resemblance to the similarly shaped article of clothing. Rather than rotate the entire structure as with the postmills, the smock mill only rotated its cap, which comprised the roof, the sails, the wind shaft and the brake wheel. The milling machinery resided in a stationary wooden body that supported the cap. This design allowed for much larger and taller mills than the postmill. Taller mills allowed extra length to the sails, which increases sail power, and gave extra height to the sail shaft, which placed the sails in stronger windfields. Most smock-mill bodies were octagonal in shape.

The evolution of the sails continued in Great Britain over the 18th and early 19th Centuries. The spring sail, developed by Scottish millwright Andrew Meikle in 1772, used a series of connected parallel shutters, which could be opened or closed according to windspeed. They also incorporated a spring device that could quickly open the shutters to prevent damage if the wind suddenly increased. In 1789, Stephen Hooper improved the design with the roller reefing sail, which allowed an automatic adjustment of the sails while the unit remained in motion. William Cubitt, a Norfolk engineer, invented a new type of sails, known as the patent sails, in 1807, that could be adjusted by a chain and a rod passing through the centre of the windshaft. The patent sails had shutters like Meikle’s design and automatic adjustment like Hooper’s sails, and the design became the basis for self-regulating sails. Initially, most windmills were built with four sails, but adding more sails could increase the power generated and smooth the rotation, at the expense of increased weight. The earliest documentation of a mill with more than four sails described the five-sailed Flint Mill in Leeds, Great Britain in 1774. Thereafter, five-, six- and eight-sail windmills were constructed.

Such tower mills reached their pinnacle of use in the late 18th Century; Britain along had over 10,000 grain mills. They were, in fact, the motors of pre-industrial Europe used in many operations: well, irrigation, or drainage pumping using a scoop wheel(s); grain-grinding with single or multiple stones; wood-milling; and processing commodities such as spices, cocoa, tobacco, and paints and dyes. But with the Industrial Revolution, steam-powered machines took over many of these applications and the windmill as an industrial tool declined. The Windmill ShrinksWith large milling operations declining as the Industrial Revolution turned to steam, and then petroleum-powered engines, the tower windmill operations either adopted the new power sources or closed. But on the North American Prairies/Great Plains, smaller windmills found renewed applications, initially for water pumping, then for small scale electricity generation.

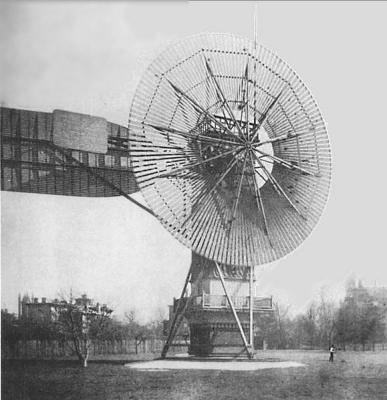

The stereotypical prairie windmill, a multi-bladed wind turbine atop a lattice tower made of wood or steel, became an icon in the rural landscapes of America and Canada. Between 1850 and 1970, over six million small mechanical wind machines were installed in the US alone. The basic design was the Halladay windmill developed in 1854, which consisted of multiple blades that turned slowly with considerable torque in low winds. Some were self-regulating in high winds. The sails now became blades of wooden slats nailed to wood rims. Most units had broad tails to orient the blades into the wind. Steel blades were introduced in 1870 allowing them to be lighter and increasing their efficiency through aerodynamic shaping than wooden ones. By improving the shape, the unit could turn at high speeds in the constant prairie winds. The higher speeds, however, required a reduction gear to reduce the rotation to match the standard pump to which they were attached. Going ElectricIn the late 19th Century, rural inhabitants used the above design to generate electricity for basic use on farms and ranches by turning direct-current generators. But such basic systems could not generate enough power for the growing demand. They were eventually replaced by connections to remotely generated electricity and power grids, such as provided by programs in the US such as the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1933 and the Rural Electrification Act in 1935. The first attempt at large-scale wind generation of electricity is attributed to Charles F. Brush of Cleveland, Ohio in 1887. His 80-ft (24 m)-tall machine had a multiple-bladed rotor 56 feet (17 meters) in diameter. The device was of post mill design with a large tail to orient the rotor into the wind. In this case, step-up gearing was required to turn the generator at its operation speed. Today, it is believed to be the first automatically operating wind turbine for electricity generation built in the winter of 1887-1888 in his back yard to provide electricity for his home and lab. It supplied 12kW of power to 350 incandescent lights, 2 arc lights, and a number of motors. The dynamo spun 50 times for every revolution of the blades and charged a dozen batteries each with 34 cells. Over its 20-year life, the turbine continuously kept the home powered.  Charles F. Brush's turbine supplied 12kW of power to 350 incandescent lights, 2 arc lights, and a number of motors for his home. The large rectangular shape to the left of the rotor is the vane, used to move the blades into the wind. For scale, note a gardener pushing a lawnmower underneath and to right of the turbine.Around the time of World War I, American windmill makers produced 100,000 windmills each year for farms and ranches, mostly used for water-pumping. By the 1930s, many small 1-3-kilowatt wind generators produced electricity in rural areas of the Midwestern and Great Plains to provide lighting for farmsteads and charge batteries for other uses such as radios. In Europe, Poul La Cour, a Dane, used aerodynamic design principles in 1891 to produce practical wind machines for electricity generation. At the time, electricity was starting to be introduced in Denmark, and La Cour felt that the wind could and should contribute to the electrification of the country. In Holland, the use of windmills to generate electricity had been discounted because of their low efficiency and problems in storing energy, but La Cour thought differently. He found financial support from the Danish Government. La Cour’s initial task was to make the mill produce constant power in order to drive the generator. The move from theory to application came through careful wind tunnel experiments. By 1896 he had started to test small models of windmills in the wind tunnel. He solved the problem by a differential regulator called the Kratostate, which was later simplified and became widely used in electricity producing windmills in the Nordic countries and Germany. La Cour built the first experimental wind generator at Askov, Denmark in the summer of 1891 and erected a more-efficient working unit in 1899. In 1902 the Askov windmill, which resembled the Dutch-style tower windmill, became a prototype electrical power plant. In 1929 a new Askov mill, four-times more efficient than the old mill, was built directly according to the late la Cour’s “ideal” design. It served the village until 1958 when alternate current replaced direct current. After La Cour’s death in 1908, the Danish Wind Electricity Society DVES initiated by la Cour in 1903 continued to promote and construct electricity-generating windmills. During World War I, electricity became scarce and wind energy became a popular means of generation. By the end of the war, many 25-kilowatt wind generators had been constructed. However, afterward large electrical plants using coal multiplied in number and the conversion to alternating current halted the spread of windmill throughout Denmark.  Some of the over 4000 wind turbines at Altamont Pass, in California. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

Now |

The BC Weather Book: |

A while back, I painted a watercolor sketch (right) of one of the windmills my grandfather built that were centerpieces of his garden (see photo below right) and later in ours. I fondly remember one that seemed so tall in my childhood, though it was at most 4 feet tall. Another inspiration came with the recent travels of my good friend Carol to Holland and her comments on Dutch windmills. As a result, my interest again peaked on windmills.

A while back, I painted a watercolor sketch (right) of one of the windmills my grandfather built that were centerpieces of his garden (see photo below right) and later in ours. I fondly remember one that seemed so tall in my childhood, though it was at most 4 feet tall. Another inspiration came with the recent travels of my good friend Carol to Holland and her comments on Dutch windmills. As a result, my interest again peaked on windmills.  Using the wind to push a boat across the water dates back at least to the 5th Millennium BCE based on a painted disc found in Kuwait containing the image of a ship under sail. The Chinese had designed sails around 3000 BCE. The Arabs began using sailing ships to establish trade around the Persian Gulf around 2000 BCE, and the Greeks and Phoenicians had begun trading by sailed ship on the Mediterranean Sea around 1,200 BCE.

Using the wind to push a boat across the water dates back at least to the 5th Millennium BCE based on a painted disc found in Kuwait containing the image of a ship under sail. The Chinese had designed sails around 3000 BCE. The Arabs began using sailing ships to establish trade around the Persian Gulf around 2000 BCE, and the Greeks and Phoenicians had begun trading by sailed ship on the Mediterranean Sea around 1,200 BCE.  We define a windmill as a machine that converts wind energy to rotational motion by means of vanes, often called sails. The earliest windmills pumped water for general use, irrigation or drainage, or milled grain, but as machinery became more complex, they were often used to provide power for manufacturing devices.

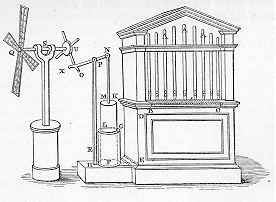

We define a windmill as a machine that converts wind energy to rotational motion by means of vanes, often called sails. The earliest windmills pumped water for general use, irrigation or drainage, or milled grain, but as machinery became more complex, they were often used to provide power for manufacturing devices. A very early application of a wind device using a horizontal axis was an ingenious device designed by Heron of Alexandria (c. 10–70 AD). His windwheel-operated musical organ, marked an early application of wind power to a complex machine. Professor Pantermalis of the Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, recreated the organ, which was played during the 2004 Athens Olympics. (Image from The Pneumatics Of Hero Of Alexandria from the original Greek translated and edited by Bennet Woodcroft, Professor of Machinery, University College, London, 1851)

A very early application of a wind device using a horizontal axis was an ingenious device designed by Heron of Alexandria (c. 10–70 AD). His windwheel-operated musical organ, marked an early application of wind power to a complex machine. Professor Pantermalis of the Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, recreated the organ, which was played during the 2004 Athens Olympics. (Image from The Pneumatics Of Hero Of Alexandria from the original Greek translated and edited by Bennet Woodcroft, Professor of Machinery, University College, London, 1851)

Although windmills had been used as water-pumping aids for centuries, their application to the vast American Plains and Prairies opened up the region to farming and ranching and its crossing by rail. Farms and ranches required water for livestock and irrigation and steam locomotives required water for their boilers, and most in this region had to be pumped from underground sources. Windmills were thus employed to pump ground water to the surface.

Although windmills had been used as water-pumping aids for centuries, their application to the vast American Plains and Prairies opened up the region to farming and ranching and its crossing by rail. Farms and ranches required water for livestock and irrigation and steam locomotives required water for their boilers, and most in this region had to be pumped from underground sources. Windmills were thus employed to pump ground water to the surface.