|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wilson Bentley,

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

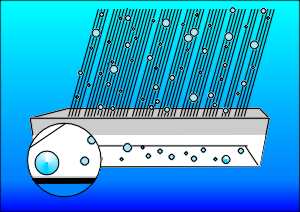

| Raindrops falling into pan filled with flour forms small dough pellets. |

Bentley saw the utility of such an experimental technique (and perhaps as a good Yankee farmer the thrift of it as well). He then set out to assure himself that the dough granules related to the true raindrop size. He calibrated his device thus:

“Drops of water of about one-twelfth of an inch [2.1 mm] and one-sixth of an inch [4.2 mm] in diameter, suspended from the end of a broom splint and a glass pipette respectively, were carefully measured and then allowed to drop into flour from height of from twelve to thirty feet [3.7 to 9.1 m].”

The resulting dough pellets “were found by careful experiment to correspond very closely in size with the raindrops that made them.” Thus assured of the validity of the results, Bentley had his collection apparatus -- a shallow tin pan and a cup of well-sifted baking flour.

“The method employed was to allow the raindrops to fall into a layer one inch deep of fine, uncompacted flour, with a smooth surface, contained in a shallow tin receptacle about four inches in diameter, which was generally exposed to the rain for about four seconds, although a longer time was given when the drops fell scatteringly. The raindrops were allowed to remain in the flour until the dough pellet that each drop always produces at the bottom of the cavity was dry and hard.”

Bentley's niece Alice recalled watching him sift flour into small tin containers and then run quickly outside with them into the hard rain. “Then later on,” she remembered, “I saw these little pellets, dried, so I asked what they were, and then he'd explain the whole thing to me. He said he was trying to measure the size of raindrops. In different storms they'd be different sizes. He had these little pellets all around the table.”

Bentley measured these raindrop “fossils” and divided them into one of five size-range categories.

| Pellet Size Category | Diameter Range | Percent of Total (867) Drops |

|---|---|---|

| Very Small | < 0.033 inches; <0.85 mm |

17* |

| Small | 0.033 to 0.055 inches; 0.85 to 1.4 mm |

34 |

| Medium | 0.067 to 0.125 inches; 1.7 to 3.2 mm |

29 |

| Large | 0.143 to 0.200 inches; 3.6 to 5.1 mm |

16 |

| Very Large | >0.200 inches; >5.1 mm |

4 |

| * Willis Moore (Descriptive Meteorology, D. Appleton and Company, 1914) speculated that this value may be low due to smaller drops not being recovered from the flour. | ||

Over the tenure of his raindrop studies, Bentley collected 344 sets of raindrop pellets from over 70 distinct storms, including 25 thunderstorms, to which he added meticulous weather data about the storm: date, time of day, temperature, wind, cloud type and estimated cloud height. He also noted the type of storm, the presence or absence of lightning, and what sector of the storm from which the samples were collected. Bentley concluded that different storms produce different size raindrops and different size distributions. Few rainfall events had uniform drop sizes, but when they did, he discovered, they were composed of either all small drops or all large drops. Low rain clouds produced mostly small drops. The largest drops, around a quarter inch in diameter, fell from the tall cumulonimbus clouds of thunderstorms. He concluded that the size of drops and snowflakes could tell a lot about the vertical structure of the storm.

From his study data, he concluded that drops of all sizes were usually present in most rains. However, small drops greatly outnumbered the large ones. The largest drops fell solely from cumulonimbus clouds that reached far up into the sky.

Bentley also observed that a small number of samples (7.5 %) were composed solely of one size category — usually small drops but sometimes only large ones. Such distributions are called monodisperse, and their cause is still an issue of debate today. Bentley felt these distributions were due to the melting of snow crystals or granular snow, which he had found to generally be of uniform size.

Bentley also used his data to conclude that the largest drops fell in rains associated with lightning overhead rather than flashing in the distance or being totally absent. From an analysis of nearly 80 data sets from each of the three lightning scenarios, the largest drops — those > 0.20 inches (5 mm) in diameter — were thirty times more numerous when lightning flashed overhead compared to the no-lightning situation and ten times greater in number with lightning overhead than when it was present but distant from the sampling location. Bentley believed that the large drops caused the lightning because they had a higher concentration of electrical charge than smaller drops.

Duncan C. Blanchard, long-time researcher in the field of cloud and precipitation physics as well as Bentley biographer, remarked that Bentley helped open a Pandora's Box of hypotheses on what really happens within a thunderstorm. Do the charged, large raindrops cause the lightning? Or does the lightning help form large raindrops? Although most atmospheric scientists would currently side with Bentley on this issue, “[t]his chicken-or-the-egg scenario is being played out in laboratories around the world today.”

Another of Bentley's deductions drawn from his measurements proposed that, based on the raindrop size distribution in thunderstorms, most thunderstorm rain came from the melting of snowflakes. He drew his conclusions form the relative volumes of large and small drops collected in thunderstorm rainfall.

“Assuming, accordingly, that the larger raindrops issue from the upper portions of the clouds and are due to the melting of snow, or, conversely, that the smaller ones originate by liquid processes alone within the lower clouds, we have a means of approximately ascertaining which process produces the major part of the rainfall. We have only to group together the individual raindrops (flour pellets) within the samples secured during various rainfalls, and weigh each group separately.”

Looking at the data from four thunderstorms, he found the total weight of the larger drops was almost twice that of the total weight of the smaller drops and thus concluded "the major portion of the rainfall of thundershowers is of snow origin."

Unfortunately, Bentley was so far ahead of his time that he wasn’t fully appreciated by contemporary scientists. They didn’t take this self-educated farmer seriously. It was 40 years — the study of cloud physics and precipitation processes would not blossom until the 1940s — before his raindrop work was rediscovered and corroborated. The first recognition of Bentley's raindrop experiments appears to have been by US Soil Conservation Service scientists J.O. Laws and D.A. Parsons, who published a paper in 1943 reporting measurements of raindrop size under various rainfall intensities using Bentley's collection method.

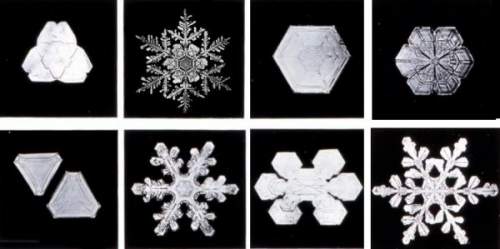

Although he dropped his study of raindrops after a few years, he continued to photograph snow crystal and speculate on the nature of snow. From his large data archive, Bentley’s analysis convinced him that the form the ice crystal took (hexagonal plate, six-sided star, hexagonal column, needle, etc) was dependent on the air temperature in which the crystal formed and fell. Nearly three decades would pass before Ukichiro Nakaya in Japan would confirm this hypothesis.

He also wanted to promote his work for its beauty, and thus submitted articles and delivered lectures that focused on his snow photography over the years. His lectures were popular, and from them he was dubbed The Snowflake Man and Snowflake Bentley by the newspapers. Over one hundred articles were published in well-known newspapers and magazines such as The Christian Herald, Popular Mechanics, National Geographic, The New York Times Magazine, and the American Annual of Photography. His best photographs were in demand from jewelers, engravers and textile makers who saw the beauty in his work. Bentley's prints and lantern slides were purchased by institutions throughout the world.

After Bentley’s father died. Wilson was left with the care of his mother, now an invalid, and running the farm, which he shared with his brother. His brother lived his wife and eight children in one half of the old farmhouse; Wilson in the other. The farm did well and they increased their dairy herd from a ten to a twenty-cow operation. He never married, and, after the death of his mother, lived alone in his side of the house. He continued to farm the acreage with his older brother for all his life.

Wilson Bentley was described as introverted, sensitive, and gentle natured. He had delicate, rounded facial features and a well-groomed head of dark hair that receded with the years. He also sported a large, bushy mustache. His only dress-up suit was in desperate need of pressing but it served his purposes for many years. When working outdoors in the winter, Bentley wore a large, dark overcoat and a soft felt hat he clamped tightly to his head using a long scarf that came down over his ears and tied beneath his chin.

Wilson Bentley was described as introverted, sensitive, and gentle natured. He had delicate, rounded facial features and a well-groomed head of dark hair that receded with the years. He also sported a large, bushy mustache. His only dress-up suit was in desperate need of pressing but it served his purposes for many years. When working outdoors in the winter, Bentley wore a large, dark overcoat and a soft felt hat he clamped tightly to his head using a long scarf that came down over his ears and tied beneath his chin.

As a grown man, Bentley was slight of frame, likely just over five feet tall and weighing around 120 pounds, but could dig a row of potatoes or pitch hay as well as any farmer in the valley. He attributed his ability for doing such delicate photograph to his lifestyle: “I never have used liquor, tobacco, or any stimulants that affect my nerves. My hand is perfectly steady.”

Though not an outgoing man, he had a sense of humor and loved to entertain by playing the piano or violin and singing popular songs. He also played clarinet in a small brass band and could imitate the sounds of many animals. In later life, he lamented that his neighbors did not really accept what he was doing.

“Oh, I guess they've always believed I was crazy, or a fool, or both. Years ago, I thought they might feel different if they understood what I was doing. I thought they might be glad to understand. So I announced that I would give a talk in the village and show lantern slides of my pictures. They are beautiful, you know, marvelously beautiful on the screen. But when the night came for my lecture just six people were there to hear me. It was free, mind you! And it was a fine, pleasant evening, too. But they weren't interested.”

Bentley’s interest in nature stretched well beyond his snow photographs. He studied auroras and kept an extensive weather journal, entering observations three times each day which included the type and amount of low, middle, and high clouds, temperature, and precipitation. Geology also fascinated him, and he would collect rock specimens as he roamed the countryside. In hopes that his love for the beauty of nature could be conveyed to others, he contributed to the Fresh Air Fund that helped bring city children out into the countryside.

In 1924, the American Meteorological Society’s first research grant was awarded to Bentley for “40 years of extremely patient work.” The monetary value of the grant was undoubtedly small, but it gave Bentley something that meant more: recognition by the scientific community for his work.

Bentley never gained monetary wealth from his snowflake photos. He remarked in 1926: “From a practical standpoint I suppose I would be considered a failure, It has cost me $15,000 in time and materials to do the work, and I have received less than $4,000 from it.” A young lady from Brooklyn once asked for some snowflake photos, enclosing $3. He sent her sixty with a note that gives us some insight to his dedication to his work: “As usual, when good snowflakes are falling, I did not stop for dinner or anything else, tho I had callers, and became ravenously hungry.”

Bentley never gained monetary wealth from his snowflake photos. He remarked in 1926: “From a practical standpoint I suppose I would be considered a failure, It has cost me $15,000 in time and materials to do the work, and I have received less than $4,000 from it.” A young lady from Brooklyn once asked for some snowflake photos, enclosing $3. He sent her sixty with a note that gives us some insight to his dedication to his work: “As usual, when good snowflakes are falling, I did not stop for dinner or anything else, tho I had callers, and became ravenously hungry.”

Bentley only occasionally left Vermont, most often to give lectures in the upper Northeast and nearby Canada. These appearances were never far from home so he could always return quickly to his work. Once, after a lecture in southern Vermont, he hastily explained to his host that he could not bear to miss the snowstorm then raging; he must leave for home on the next train.

Wilson occasionally submitted technical reports to the US Weather Bureau’s publication Monthly Weather Review. Although he received scant recognition from most scientists, he did receive encouragement from Weather Bureau chief meteorologist Dr William J. Humphreys who helped him publish a collection of his photographs. Humphreys wrote the technical introduction and appeared as co-author.

The book Snow Crystals by W. A. Bentley and W. J. Humphrey was published by McGraw-Hill in November 1931. It contained 2500 selected snow crystal photos plus 100 of frost and dew formation. The book has since been republished by Dover Books. In late November following Thanksgiving, Bentley received three copies of the book and promptly thanked Humphreys in a note dated December 1, “…I am delighted with it.”

In early-December 1931 returning from Burlington, Wilson Bentley, ill dressed for the weather, walked six miles through a slushy snowstorm to reach his home. On December 7, he wrote in his journal “Cold north wind afternoon. Snow flying.” This was the last entry he would make after 47 years. Not long thereafter, he caught a cold, which untreated, grew into pneumonia. “Snowflake” Bentley died on 23 December at the age of 66. In March of that year, he had taken the last of his photomicrographs of snow, still using the same camera system that took the first one.

Although his father and brother thought Wilson’s snow photography a lot of nonsense and not the proper thing for a farmer to do, Wilson broke unique ground in the early days of modern meteorology as well as microscopic photography. His biographer, cloud physicist Duncan Blanchard, dubbed him “America’s First Cloud Physicist.” The Burlington Free Press wrote in a Christmas Eve obituary for Bentley:

“Longfellow said that genius is infinite painstaking. John Ruskin declared that genius is only a superior power of seeing. Wilson Bentley was a living example of this type of genius. He saw something in the snowflakes which other men failed to see, not because they could not see, but because they had not the patience and the understanding to look.

Truly, greatness blooms in quiet corners and flourishes under strange circumstances. For Wilson Bentley was a greater man than many a millionaire who lives in luxury of which the 'Snowflake Man' never dreamed.”

On the morning he was laid to rest in the Jericho Center cemetery, it began to snow, leaving a dusting over the burial ground. His small tombstone reads, with typical New England brevity:

For a video on Snowflake Bentley, click on the image below.

I am indebted to Duncan C. Blanchard for the extensive research on W.A. Bentley found in his biography of Bentley titled The Snowflake Man. The facets of Bentley's life presented here are based on materials from that book. I have reviewed the book in the Weather Reviews section of the Weather Doctor.

I am indebted to Duncan C. Blanchard for the extensive research on W.A. Bentley found in his biography of Bentley titled The Snowflake Man. The facets of Bentley's life presented here are based on materials from that book. I have reviewed the book in the Weather Reviews section of the Weather Doctor.

|

Now AvailableThe Field Guide to Natural Phenomena: |

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Order Today from Amazon! | |

|

|

To Order in Canada: |

To Order in Canada: |