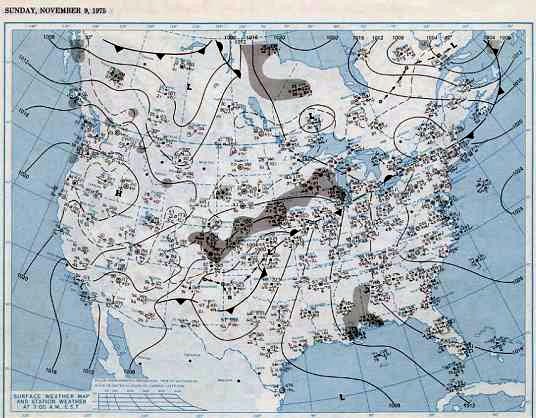

Synoptic Situation on 9 November 1975 at 0630CST

Courtesy, NOAA, NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project

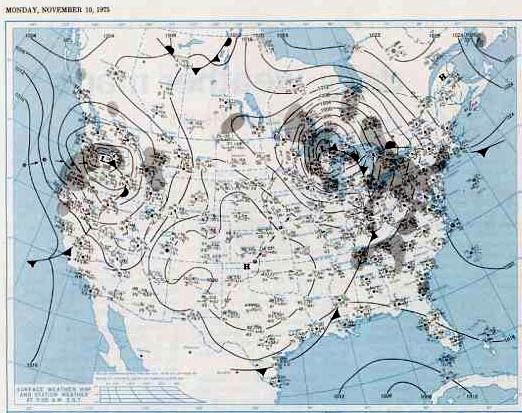

By morning the following day (0700 EST), a definite low cell had formed over central Kansas with central surface pressure of about 1000 mb. The front, on which the cyclonic development had begun, started showing the classical warm front-cold front wedge pattern. At the 500 mb level, a definite upper air trough had formed behind (west) the storm center indicative of cold air invasion to the west of the storm. Unlike the Armistice Day storm, the cold was not as intense. Low temperatures through the Plains States that morning were generally in the 20-30 oF (-7 to -1 oC) range. Based on forecasts of the storm’s strength and movement, gale warnings were issued for eastern Lake Superior for later that day. At 2 AM EST, 10 November. the gale warnings were upgraded to storm warnings with winds forecast to blow at 25-50 knots (29-58 mph /46-92 km/h) from the northeast then diminish to 28-38 knots (32-44 mph /52-81 km/h) from the northwest as the storm center passed over mid Lake Superior. These forecasts unfortunately underestimated the actual storm strength and wind speeds, which exceeded 70 knots (80 mph /130 km/h), hurricane threshold, and gusted to 85 knots (98 mph /157 km/h).

Synoptic Situation on 10 November 1975 at 0630CST

Courtesy, NOAA, NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project

In the next 24 hours, this storm showed rapid and intense development as it sped to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan across eastern Iowa and central Wisconsin. The central pressure dropped from 1000 to 984 mb over that period and would bottom out later on 10 November at 980 mb, not quite reaching the criterion for a bomb storm. Unlike the 1940 Armistice Day storm, the Fitzgerald storm was rather compact and moved so quickly that most precipitation fell close to the storm track. Nevertheless, precipitation exceeding 0.4 inches with totals as high as 1.64 inches (northeastern Wisconsin) fell across Missouri, Iowa, Wisconsin and Michigan. As the trailing cold front swept across the Ohio Valley and Gulf States, rainfalls totaled as much as 3.54 inches at Mobile, Alabama and 0.84 inches at Evansville, Indiana.

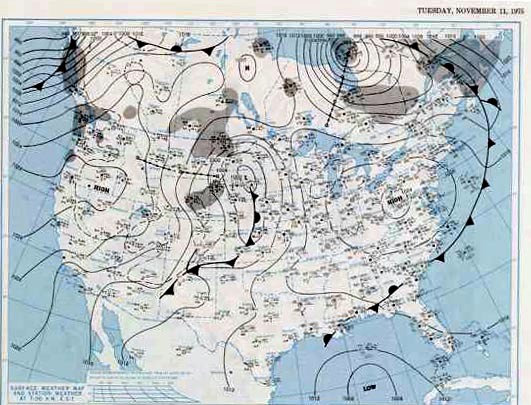

The storm continued to charge northward across Lake Superior into northern Ontario at White River, and by the morning of 11 November it had crossed over James Bay to the southeastern edge of Hudson Bay, its central pressure rising a few millibars to 983 mb.

Synoptic Situation on 11 November 1975 at 0630CST

Courtesy, NOAA, NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project

Fury on the Lake

While this storm brought rain and snow to many areas along its path and high winds buffeted the region, its infamy rests on the storm’s impact on the Great Lakes, particularly the sinking of one ship: the large ore carrier SS Edmund Fitzgerald.

November gales on the Great Lakes are legendary and have been called “Freshwater Furies” and “Freshwater Hurricanes” for their high winds. Nearly a third of all storm-related shipwrecks on the Great Lakes have happened in November. On the Great Lakes, the designation “storm” is the highest rating that may be given a low-pressure system when winds exceed 47 knots (54 mph / 86 km/h). A typical year might count between 30 and 35 “storms” over the span. Historical weather records (covering over 170 years) indicate that at least 20 storms crossed the Great Lakes with winds blowing at hurricane force, and 19 of those blew in November.

As Gordon Lightfoot sang in his epic song The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald:

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

of the big lake they call "Gitche Gumee."

"Superior," they said, "never gives up her dead

when the gales of November come early!"

One reason for this spike in storminess during November is that many Lake-crossing storms derive large transfers of heat and moisture from the warm lake waters into the relatively colder air above, enhancing the upper-level moisture content and convection within the storm. (See my piece: “The Winds of November” for more.)

The Loss of the Edmund Fitzgerald

The Great Lakes freighter named the Edmund Fitzgerald was launched on 8 June 1958, one of the largest ships on the Great Lakes for over a decade at 730 feet (220 m) long and 75 feet (23 m) wide. Nicknamed “Mighty Fitz” and “The Big Fitz” it was constructed to carry taconite (a variety of iron-bearing sedimentary rock) for the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. It was named for the company’s president and Board Chairman Edmund Fitzgerald, whose father had been a lake captain.

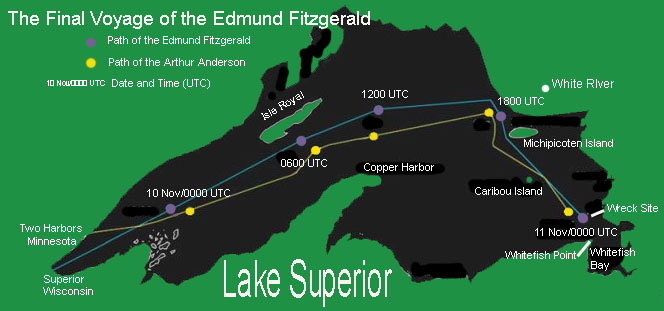

On its fateful voyage, the Fitzgerald left Superior, Wisconsin on Sunday afternoon, 9 November 1975 captained by Ernest M. McSorley. She held a full cargo (26,116 tons of taconite) bound for a steel mill on Zug Island near Detroit, Michigan. “Mighty Fitz” was joined by the Arthur M. Anderson, a freighter carrying a similar cargo, which had left Two Harbors, Minnesota headed for Gary, Indiana under Captain Jesse “Bernie” Cooper. As they crossed Lake Superior at a speed of about 14 knots (16 mph / 26 km/h), they encountered the storm system as it was crossing Lake Superior.

The National Weather Service (NWS) Office issued a gale warning for Lake Superior at 1:39 PM CST (1939 UTC) on the 9th. (Since the ships changed time zones during their crossing of Lake Superior from Central to Eastern Standard Time, I will use the UTC time stamp to avoid confusion. Eastern Standard Time is 5 hours earlier than UTC, and Central Standard Time is 6 hours earlier.) Both captains knew of the gale warning.

Later, at 2239 UTC, the forecast was updated, calling for “easterly winds 32 to 42 knots [37-48 mph / 59-78 km/h], becoming southeasterly Monday morning, and west to southwest 35 to 45 knots [40-52 mph / 65-83 km/h] Monday afternoon, rain and thunderstorms, waves 5 to 10 feet [1.5-3.0 m] increasing to 8 to 15 feet [2.4-4.6 m] Monday.”

At 0200 UTC, 10 November, NWS upgraded the gale warning to a storm warning with “northeast winds 35 to 50 knots [40-58 mph / 65-92 km/h], becoming northwesterly 28 to 38 knots [32-44 mph / 52-70 km/h], waves 8 to 15 feet [2.4-4.6 m].” At about this time the storm was centered in central Wisconsin, and the ships were 20 miles (32 km) or so south of Isle Royal.

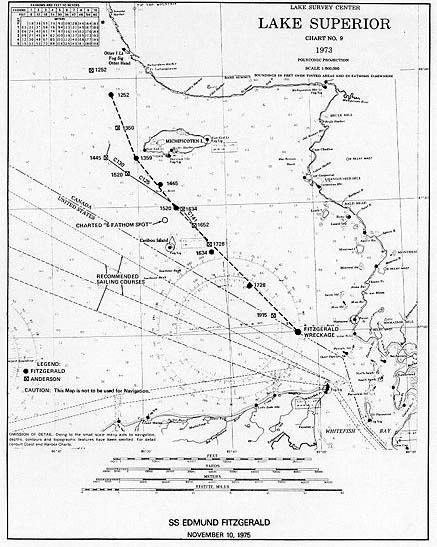

At 0700 UTC, November 10, the Fitzgerald was about 45 miles (72 km) north of Copper Harbor, Michigan with the Anderson not far behind. She reported winds from the north-northeast at 35 knots (40 mph / 65 km/h) and waves of 10 feet (3m). Early on the morning of the 10th, both captains agreed to alter their course, sailing closer to the Canadian shore of Superior to take advantage of the shorter wind fetch. This decision was based on the forecast of northerly gales (east to northeast shifting to northeast by the afternoon of the 10th). Fetch, the distance the wind blows across a water surface, is related to wave height, the longer the fetch, the greater the potential wave height. Similarly, wind speed and duration also increase wave height as they increase. While ship captains cannot control the wind speed or its duration, they can reduce the fetch their vessels experience, which is the reason, the two ships headed toward the Canadian shoreline.

At 1034 UTC on November 10, the new NWS updated forecast predicted “north to northwest winds 32 to 48 knots [37-55 mph / 59-89 km/h] this afternoon becoming northwesterly 25 to 48 knots [29-55 mph / 46-89 km/h] tonight and westerly 20 to 30 knots [23-34 mph / 43-56 km/h] Tuesday, waves 8 to 16 feet [2.4-4.8 m] decreasing Tuesday.’’

A few hours later, the storm had crossed Lake Superior west of Michipicoten Island and was now centered over White River, Ontario. At 1300 UTC on November 10, the Anderson sat 20 miles (36 km) northwest of Michipicoten Island — with the Fitzgerald around 8 miles (13 km) ahead — and reported winds from the south southeast at 20 knots (23 mph / 43 km/h) and waves of 12 feet (3.6 m). At the same time, the M/V Simcoe located 15 miles (24 km) to the southwest of the Anderson reported winds from the west at 44 knots (51 mph / 81 km/h) and waves of 7 feet (2.1 m). Concurrently, Stannard Rock Weather Station reported winds from the west northwest at 50 knots (58 mph / 92 km/h), gusting to 59 knots (68 mph / 109 km/h), and the Whitefish Point Station reported winds from the south southwest at 19 knots (22 mph / 35 km/h), gusting to 34 knots (39 mph / 63 km/h).

As the vessels approached Michipicoten Island, they altered their heading to the southeast to sail toward Whitefish Bay and the approach to the Sault Ste. Marie Locks. Based on the log of the Anderson, the ship likely encountered the central region of the storm sometime after local noon as the observed winds blew from the west northwest at 5 knots (6 mph / 10 km/h) (the calmer “eye” of the storm). An hour later on the west side of the tempest, they had risen to 42 knots (48 mph / 77 km/h). It was snowing heavily.

The ships were located in the vicinity of Caribou Island at 2030 UTC when Fitzgerald reported to the Anderson that a fence rail was down, a couple of vents were lost, and the ship had developed a list. Captain McSorley indicated that he would slow down to allow the Anderson to close the distance between the vessels. This decision strongly suggests McSorley suspected something was wrong, possibly of a very serious nature, because by slowing, it delayed their arrival in the safety of Whitefish Bay.

Reconstructed Location in Edmund Fitzgerald's Last Hours

Courtesy, NTIS Report, US Department of Transportation

During mid-afternoon of 10 November (1800 UTC), sustained winds of 25-30 knots (29-34 mph / 46-56 km/h)were blowing over the eastern lake with gusts up to 87 knots (100 mph / 160 km/h) and waves as high as 35 feet (11 m). The Anderson observed a sustained wind speed of 67 mph (77 mph / 124 km/h), 70-75 knot gust (80-86 mph / 149-159 km/h) and waves 18-25 ft (5.5-7.6 m) south of Caribou Island.

At 2110 UTC, McSorley informed the Anderson that the Fitzgerald had lost both radars and would need navigational assistance. At about this time, the Coast Guard advised lake traffic that visibility was poor due to heavy snow and that they should seek safe harbor. They also advised that the Whitefish Point lighthouse and navigation beacon had been knocked out by the storm and that the Soo Locks at Sault Ste Marie had closed.

Between 2200 and 2230 UTC, McSorley told both the Anderson and the Swedish vessel Avafors that the ship was listing badly and they were taking heavy seas over the deck. The pilot aboard the Avafors, Capt Cedric Woodard, heard a voice in the background say “Don’t allow nobody on deck” followed by a comment by McSorley that Woodard only poorly heard mentioning a vent. The veteran captain McSorley also remarked: “This is the worst storm I have ever been in.”

With the cargo they were carrying, both vessels had about ten feet (3 m) of freeboard (the height of the deck above still water) and waves were regularly rolling over the decks. Cooper noted at around 2330 UTC, the Anderson was overtaken by two waves he estimated as 30 ft high (10 m). The first buried the after cabins and damaged a lifeboat. The second washed over the bridge deck, 35 feet (10.7 m) above the ship’s waterline.

At 0000 UTC on the 11th (evening of the 10th locally), the Anderson informed the Fitzgerald that it was about 8.8 miles (14 km) ahead and 1.2 miles (2 km) east. In the last communication with the Anderson about ten minutes later, McSorley indicated: “We are holding our own.” This was the final radiotelephone contact between the two vessels.

Ten minutes later, (7:20 pm EST /0020 UTC), the Anderson’s radar could not pick up the Fitzgerald nor was it visibly sighted, even though increased visibility allowed observations from the Anderson of shore lights 32 km (20 miles) distant and three approaching ships as far as 30 km (19 miles) away. At a separation of 16 km (10 miles), the Fitzgerald’s lights should have been visible. With all attempts to raise her unsuccessful, Captain Cooper of the Anderson notified the US Coast Guard at Sault St Marie, Michigan that the Fitzgerald was missing and, at 0132 UTC, they began a search operation.

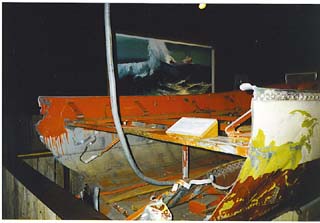

Edmund Fitzgerald's Lifeboat Found By Anderson During Search

Photograph by James Lefevre, public domain

The initial search effort by the Anderson, was assisted by a second freighter, William Clay Ford. A third nearby freighter, the Canadian vessel Hilda Marjanne, was foiled by the weather. The US Coast Guard launched three aircraft, and asked vessels in the vicinity for assistance. The preliminary search recovered debris from the Fitzgerald including a portion of a lifeboat with “Edmund Fitzgerald No. 1” on it and an intact, but damaged lifeboat, but no survivors.

We will never know for sure what happened in those last minutes, despite countless theories, but weather most likely was a main factor. What we do know is that wind speeds over southeastern Lake Superior were likely blowing above 45 knots (51 mph / 83 km/h) by 0000 UTC (11 November) and modeled wave heights suggests seas likely reached nearly 26 ft (8 m) in height, moving in from the west. At this time, the Anderson reported northwest winds at 50 knots (58 mph / 92 km/h). Modeled winds suggest gusts between 70-75 knots (80-86 mph / 129-138 km/h) and waves to 25 ft (7.5 m). (The model simulation of the event was undertake by NOAA using the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory Wind-Wave Model.) It is of note that the Fitzgerald went down at the time and place shown by the model simulations to have the worst wind/wave conditions in that area.

The Legend Lives On

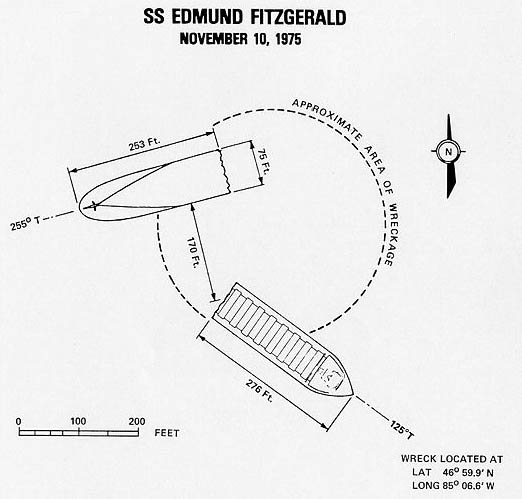

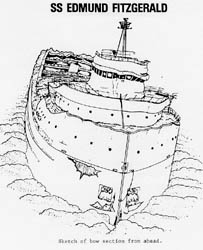

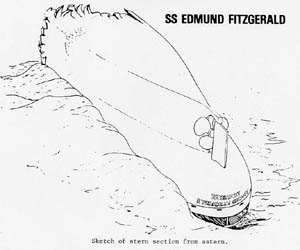

The Edmund Fitzgerald now rests on the bottom of Lake Superior, fractured in two large pieces at a depth of 530 ft (162 m), in Canadian waters just north of the international boundary. With her sleep the 29 crew members of the ship. Her 200-lb (90 kg) bronze bell recovered from the wreck in 1995 now sits at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Whitefish Point, Michigan.

|

|

|

Position of Edmund Fitzgerald Wreck Pieces on Lake Bottom

Courtesy, NTIS Report, US Department of Transportation |

Shorty after the ship was lost, Canadian folk singer/songwriter Gordon Lightfoot composed a song based on the incident entitled The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. The song was included on his 1976 album Summertime Dream, released in June 1976 but recorded at the turn of the year. It was Lightfoot’s twelfth album and reached the twelfth spot on the Billboard pop charts. The single released in August topped the Canadian hit parade (on both pop and country charts) and reached number 2 in the US, both peaks occurring in November, the first anniversary of the wreck.

According to Lightfoot’s webpage, he “wrote Wreck Of The Edmund Fitzgerald as a tribute to the ship, the sea, and the men who lost their lives that night. He was inspired by a line in a Newsweek Magazine article Great Lakes: The Cruelest Month by James R. Gaines with Jon Lowell that read: “According to a legend of the Chippewa tribe, the lake they once called Gitche Gumee ‘never gives up her dead.’” Lightfoot transformed this line into the opening lines of the song.

When asked recently what he thought his most significant contribution to music was, he replied it was this song. The imagery of the song and haunting musical accompaniment has kept it playing through the years with annual peaks during the anniversary month.(Note that the song has taken artistic license with some of the facts including conjectures as to what actually happened during those fateful last minutes. Many credit the song with making the Fitzgerald sinking the most well known ship lost on the Great Lakes.

The UTube version below is of the original song recorded at a live performance in 1979. Lightfoot has since altered one line during live performances “as a result of recent findings that it was waves and not crew error that lead to the shipwreck.”

His was not the only musical tribute to the incident. A decade later, Steven Dietz and songwriter/lyricist Eric Peltoniemi wrote a musical entitled Ten November in memory of the Fitzgerald’s sinking. For the 30th anniversary in 2005, the musical was re-edited into a new musical called The Gales of November, which premiered in St Paul, Minnesota, ironically at the Fitzgerald Theater (named after native son F. Scott Fitzgerald). The theater is the oldest existing stage venue in the city and home to the popular A Prairie Home Companion radio broadcast on Minnesota Public Radio.

Learn More on Weather and Storms from these Relevant Books

Chosen by The Weather Doctor

- Heidorn, Keith C.:And Now...The Weather, 2005, Fifth House, ISBN 1894856651

- Burt, Christopher C.: Extreme Weather: A Guide and Record Book, 2004 (pb), W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 039333015X.

- Williams, Jack: The AMS Weather Book: The Ultimate Guide to America's Weather , 2009, University Of Chicago Press, ISBN: 0226898989.

Written by

Keith C. Heidorn, PhD, THE WEATHER DOCTOR,

November 1, 2010

The Edmund Fitzgerald Storm ©2010, Keith C. Heidorn, PhD. All Rights Reserved.

Correspondence may be sent via email to: see@islandnet.com.

For More Weather Doctor articles, go to our Site Map.

|

Now Available The Field Guide to Natural Phenomena:

The Secret World of Optical, Atmospheric and Celestial Wonders

by Keith C Heidorn, PhD,

and Ian Whitelaw |

I have recently added many of my lifetime collection of photographs and art works to an on-line shop where you can purchase notecards, posters, and greeting cards, etc. of my best images.

Order Today from Amazon! |

|

|

|

|

Home |

Welcome |

What's New |

Site Map |

Glossary |

Weather Doctor Amazon Store |

Book Store |

Accolades |

Email Us