|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||

The Great Chicago Snow of 1967Watching the news reports of the fifteenth strong storm to hit the Victoria–Vancouver region this winter has left me with a small sense of disappointment in having left the area this past summer. I think many meteorologists have a strong sense of wanting to experience weather at its wildest, I know I do. It gives us stories that we can relate to the numbers and equations. While the rest of the population are perhaps not as keen to see bad weather, they too revel in the stories they can later tell to distant friends and family or to save for reminiscences to children and grandchildren.

First, A Lotta ThunderJanuary 1967 had been a roller coaster for weather in the Chicago area. A week or so prior to the storm, temperature had plummeted to a bone-chilling 8 oF (-13 oC). On 24 January, the temperature had soared to a spring-like 65 oF (18.3 oC) and the low that morning was 44 oF (6.7 oC), both records for the date that still stand. Thunderstorms rolled across northeastern Illinois during the evening. The wind gusts, reaching 48 mph (77 km/h) at Chicago's Midway Airport, blew down a wall of a building under construction at 87th and Stoney Island. The collapse killed one worker and injured four others. In the southwestern section of the city, funnel clouds were sighted. On Wednesday 25 January, a cold front was moved across the upper Midwest replacing the mild weather of the previous day with more seasonal temperatures. A strong (1032mb / 30.48 in Hg) high pressure cell of arctic air situated over the Canadian Prairies was pushing into the northern American Plains. An upper level trough moving across the southern Rockies spawned a surface low near the Texas Panhandle. By midnight, the developing low had moved to central Oklahoma. As the upper level winds swung eastward, the cyclone developed the characteristic frontal wedge and moved toward the Ohio Valley. While the low headed northeastward, the Canadian high, rather than push southeastward which is most often the case, slid eastward over Lake Superior and funnelled dry arctic air from the northeast into the Great Lakes. The low, now situated over southern Missouri, sent warm and very moist air out of the Gulf Coast northward toward the Lakes. Where the two contrasting air streams met, the weather would become downright nasty. Late Wednesday morning, the Chicago office of the US Weather Bureau issued the following forecast: ISSUED 945 PM WEDNESDAY JANUARY 25TH During the night, it became obvious that the storm track would move south of Chicago through the Ohio Valley, putting Northeastern Illinois and Northern Indiana in the most likely region for heavy snow. With a strong pressure gradient between the two weather systems, the arctic winds would howl over Lake Michigan, and add a lake-effect component to the storm's snowfall. In addition, the strong winds would cause considerable blowing and drifting of the snow.  Surface Weather Map for Midnight CST 26 January 1967. Click for larger map.Comes the StormBased on these factors, the Chicago forecast office issued the following weather warning overnight: ISSUED AT 345 AM THURSDAY JANUARY 26 As the storm system approached, the winds shifted to the north, then backed to northeast and rose to 15-20 mph (24-32 km/h). Snow began early Thursday morning (around 5 AM), but commuters generally ignored the heavy snow warning, and most Chicagoans made the morning trip to work and school with only minor incidents. But as the storm moved closer to the city, it became obvious that the forecast accumulation was too low, and Chicago sat in a small sector of the storm which would receive more snow than expected. The Weather Bureau's mid-morning forecast upped the snowfall accumulation expected: ISSUED AT 945 AM THURSDAY JANUARY 26 Thursday 26 January: Faster and DeeperDuring the day, the upper level trough swung through the mid and lower Mississippi Valley. An upper level low began to develop near the Missouri/Arkansas border. As the storm system strengthened, so did the clash of cold, dry and warm, moist airs. In Chicago and surrounding areas, the snow was falling fast and accumulating deep. By noon, 8 inches (20 cm) had already accumulated causing O'Hare International Airport to shut down. By noon, hotels across the city faced an unexpected need for rooms as conventioneers, packing to go home, had their flights cancelled. Then word spread across the city of the awful travel conditions and many Chicagoans tried to book rooms rather than return to suburban homes.  O'Hare International AirportMeigs Field located on the lakeshore reported thundersnow. Winds gusted to 53 mph (85 km/h) were reported at Midway Airport. The high winds produced considerable blowing and drifting of the heavy snowfall. During the late morning hours, snow accumulated at a rate of 2 inches (5 cm) per hour. Many businesses and schools released their employees and students early, others just left work early, but the commute was a nightmare. At many street corners, commuters by the dozens waited in vain for buses that never came. During the early afternoon rush, the only transportation running with any regularity was Chicago's famed L trains that moved above the snow-filled streets. Unfortunately, not everyone was able to get the L out of Chicago. Rush hour definitely was not a rush, more a "sit-and-wait" that dragged on for hours as traffic tried to crawl out of the city. Many never arrived home. Those that did often arrived hours later than usual. One woman reported the usual 35-minute drive home from her office on Wacker Drive to the North Side, took 4 hours that evening.

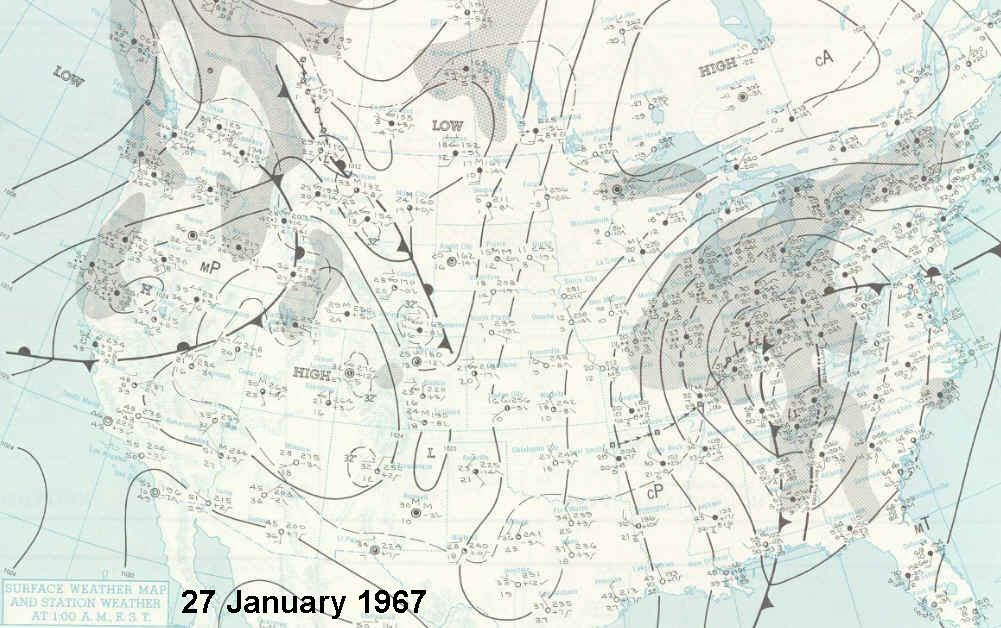

Rather than be trapped in their cars, most drivers abandoned their vehicles where they sat and decided to walk. But not everyone got home, even by travelling on foot. The deep snow, tall drifts and howling winds physically exhausted many walkers fighting the stinging snow. Some spent the night at gas stations, in schools or in buses and trains. Others camped out in downtown hotels, O'Hare International Airport, and even in stranded cars. Others decided to stay at work and many took extra shifts because their replacements never arrived. In the south suburb of Markham, 650 students in four schools camped out in the school libraries and gymnasiums because school buses could not get through. The snow affected the commuter rail lines as well. Thousands of commuters daily road the Chicago, South Shore and South Bend Railroad, the last interurban electric line, into the city, but by evening it ceased operating due to the heavy snow, and would not resume its full schedule until 20 February. The Expressways and Tollways fared no better. All attempts to clear these highways were fruitless as the howling northerly winds blew the snow back minutes after the snowplows passed. As a result, these thoroughfares, like the city streets, became parking lots. Around midnight, the winds shifted to the north and continued to back to the northwest as the low pressure center, whose central pressure now stood at 997mb (29.44 in Hg), slid into central Indiana. Blowing at gale force, the winds caused severe drifting, leaving drifts as high as 6 feet (1.83 m) in Chicago and 8-10 feet (1.40-3.05 m) at Ogden Dunes on the shores of Lake Michigan in Indiana.  Surface Weather Map for Midnight CST 27 January 1967. Click for larger map.Friday 27 January: Snow Ends, But...Morning light brought the realization that the nation's second largest city was paralyzed. All Chicago's transportation systems were at a standstill. The airports and the city's main thoroughfares were closed; streets were clogged with abandoned and stranded vehicles — an estimated 50,000 cars and 1100 CTA buses. Michigan Avenue in the downtown core was deserted save for a few hardy pedestrians, some sporting snowshoes. Helicopters were used to deliver medical supplies to hospitals and food and blankets to stranded motorists.

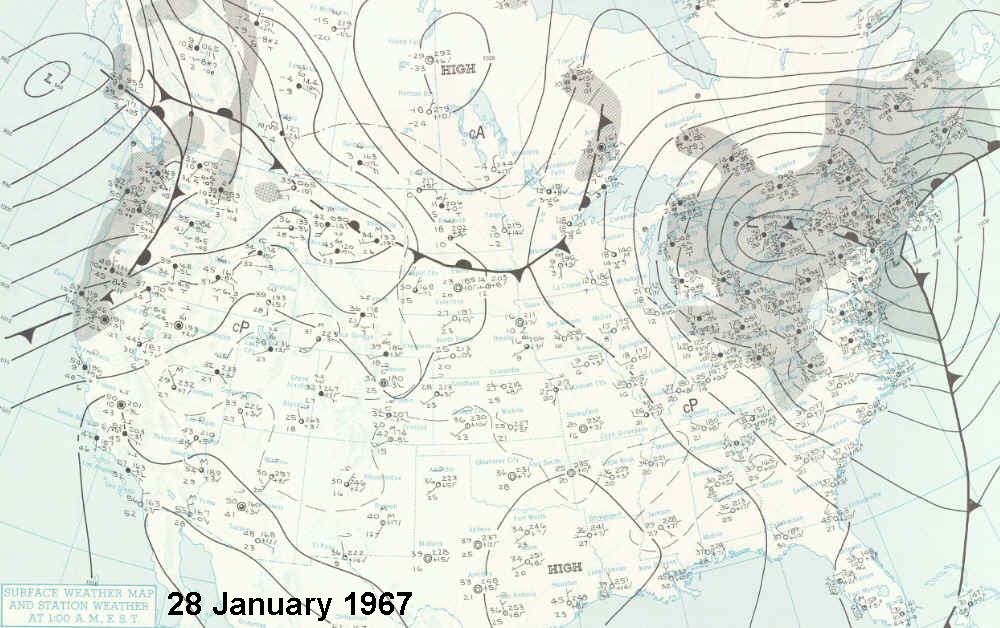

Those who decided to venture out soon gave up and returned home. The few who reached their workplace generally arrived so late, they too turned around and went home. Understaffed grocery stores faced crowds of people waiting to buy food, and shelves were soon cleared of bread and milk. In many buildings and homes, heating oil ran low, and delivery trucks could not access the buildings due to the deep snow. Even emergency workers could not get around normally. Firefighters unable to take their trucks down blocked streets walked to fires. Helicopters flew emergency cases to hospitals. Several expectant mothers reached delivery rooms by bulldozer, snowplow and toboggans, but many delivered at home. In some areas on the west and near-south sides of the city looting was rampant; 273 looters were arrested. A young girl was killed, caught in the crossfire while police shot at looters. Heavy snow continued unabated until around 0400 on the 27th. The snow finally stopped falling onto the city at 10:10 AM, 29 hours after it had begun. The official measurement of 23.0 inches (58.4 cm) confirmed the storm was the single greatest snowstorm to date in Chicago history. At Ogden Dunes, the Weather Bureau Cooperative Observer Robert A Ward reported snow depths had reached 21.5 inches (54.6 cm) with drifts 8-10 ft (1.40-3.05 m). But all was not over for Chicago and vicinity. The cleanup had barely begun and for some hours, the winds continued to rearrange the drifts, often tossing back what plows and shovels had cleared. The biggest obstacle the cleanup crews faced was the sheer number of abandoned vehicles that had to be moved before the streets could be cleared. In some neighbourhoods, residents formed impromptu, cooperative shovelling operations to clear their blocks. Mayor Richard Daley sent a workforce of 2500 with 500 pieces of equipment to clear the streets. Working all night, they hoped to get the city back on its feet. The county amassed 150 workers and 75 pieces of equipment, and the state used 200 pieces of equipment to battle the snow.  Surface Weather Map for Midnight CST 28 January 1967. Click for larger map.The low that had caused all the trouble continued to deepen (990mb / 29.23 in Hg) and began to occlude as it moved into Ohio and continued on a northeasterly track over Lake Erie. By midnight it was over south central Ontario. Saturday 28 January: Cleaning UpBy morning, city, county and state work crews had made progress against the mass of snow. Rapid transit lines and commuter rail service were again operating, and CTA buses were able to cover most routes. In addition to crews from the local governments, the Chicago region received aid from their neighbouring states Iowa, Wisconsin and Michigan who sent snow removal equipment including giant snowblowers.  Cleaning lanes on Outer Drive, location 16th to 12th StreetsSnow was initially hauled by dump truck to the Chicago River, but the immense amount — an estimated 75 million tons — proved a "storage" problem. Many empty railcars were filled then with the snow and sent south to Florida and Texas. With tongue-in-cheek humour, the cars destined for Florida were designated as gifts for Florida children who had never seen snow. In some places, the snow pushed into immense piles later hardened into ice, and some of these mini-glaciers lasted until March. The AftermathBy Sunday 29 January, the major highways in the Calumet region southeast of the city finally reopened. Many area side streets, however, would remain snowed in until February. O'Hare International reopened at 6 PM Sunday evening. But conditions were not optimal by Monday's morning rush hour. Motorists were urged to leave their cars at home and take public transportation, and this put a strain on the system. Schools remained closed until Tuesday as many teachers were still unable to get to classes, and heating fuel was low in many schools. Relief from snow was not long. Another system moved across the region on Wednesday 1 February and dumped an additional 4 inches (10 cm) on the city. Remembering the chaos of the previous week, many residents left work early and there was a run on groceries stores and hotels. A third storm hit on Sunday 5 February but city crews were able to keep streets and roads clear and traffic moving. By Monday morning, an additional 8.5 inches (21.6 cm) had accumulated with 11 inches (27.9 cm) in the suburbs. The Tally and the Record BookBy the time the series of storms had ended, the 1967 snowstorm likely caused the biggest disruption in the City of Chicago since the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Sixty deaths were attributed to the storm, a large portion from heart attacks while shovelling snow. One clergyman was run over by a snowplow, and a ten-year-old girl had died in the crossfire shooting between police and looters. The economic losses came to $150 million, about $904 million in 2006 dollars. The cost of snow removal alone for Chicago tallied $8-10 million ($48.2-69.2 million). The weather records set for the city include:

Officially, the 1967 snowstorm was the greatest on record for Chicago since official records began in 1870, and no account of any greater snowfall previous to 1870 in unofficial records back to 1859 has been found. The only possible competition might have come during Illinois' Winter of the Deep Snow in 1830-1831 when Chicago was still Fort Dearborn. Learn More About Weather From These Relevant Books

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now Available in the US! |

The BC Weather Book: |