|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| ||||||||||||||||||

The Armistice Day Storm of 1940

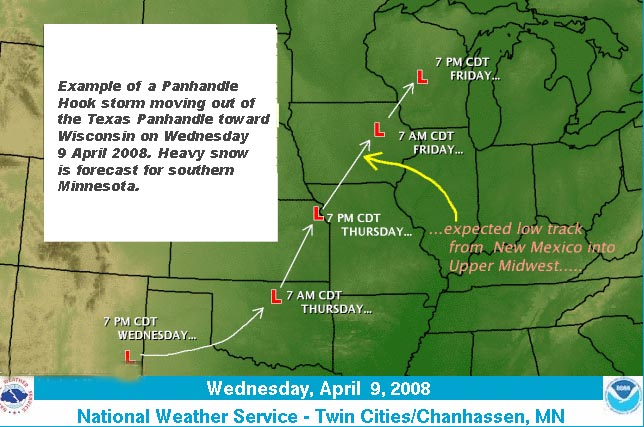

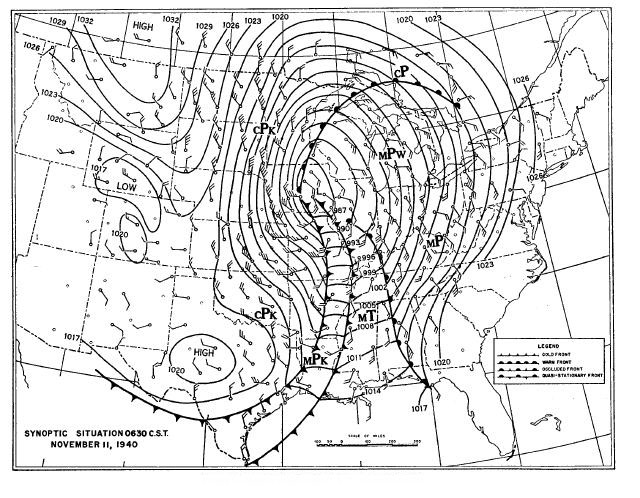

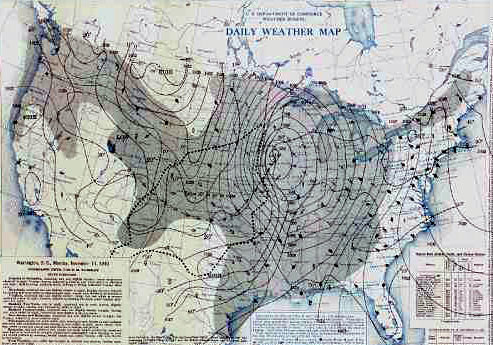

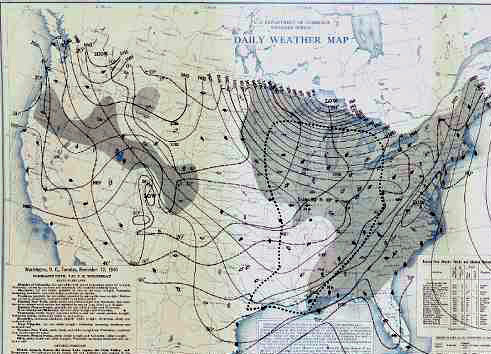

The storm had some of the surprise elements that caused great hardships to residents of the same general region in January of 1888, the so-called Children’s Blizzard. As with that storm, the US Weather Bureau had not forecast the storm and missed the maturing storm because the office in charge of the warnings (located in Chicago) had closed for the night. Thousands of duck hunters enjoying good hunting weather had heard a cool down with some snow was coming, and therefore, were unprepared for the sudden and fierce onslaught that hit the marshes of the Upper Mississippi Valley on the 11th. In 1940, the US Weather Bureau was transferred from the US Department of Agriculture to the Department of Commerce as the emphasis of the Bureau’s forecasting services switched from agriculture to aviation. The responsibility for issuing weather warnings was given to district forecast centers and the Chicago office was in charge for the region at issue here. They issued four general forecasts daily plus all warnings. However, there was not the 24/7/365 coverage of the weather at the time that we enjoy today. Each evening the office closed. Prelude to StormToday, we would likely class the Armistice Day Storm as a Panhandle Hook (aka a panhandle hooker or Texas hooker). According to the US National Weather Service glossary, such storms are a low pressure systems that originate in the panhandle region of Texas and Oklahoma, and initially move easterly and then "hook" or recurve more northeasterly toward the upper Midwest or Great Lakes region. In winter, these systems usually deposit heavy snows north of their surface track. They typically form further south than the more common Colorado Lows.  Example of Panhandle Hook Storm |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

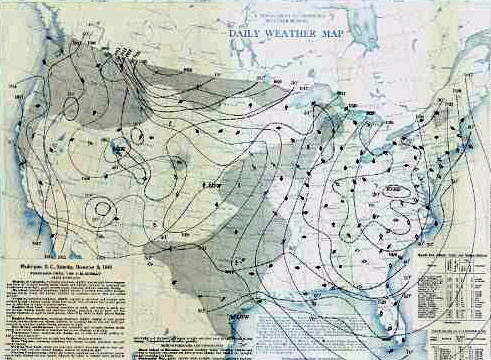

In contrast to the arctic air, a broad flow of moist tropical air moved northeastward from the western Gulf of Mexico into the middle Mississippi Valley in the upper atmosphere. This conforms with the conditions for a panhandle storm, which at midday of the 10th lay over the Oklahoma Panhandle.

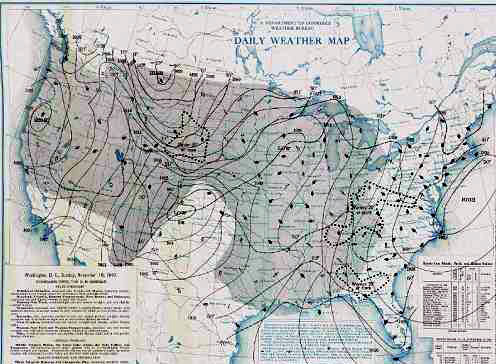

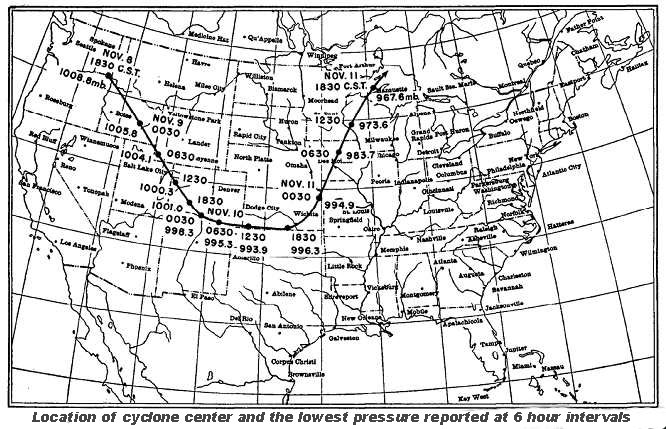

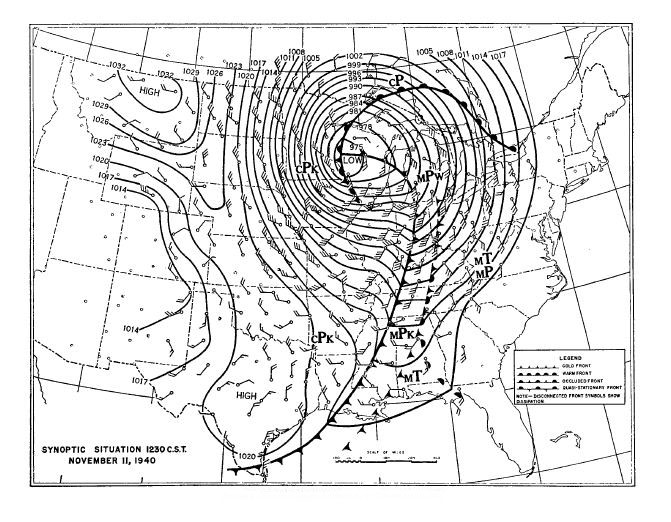

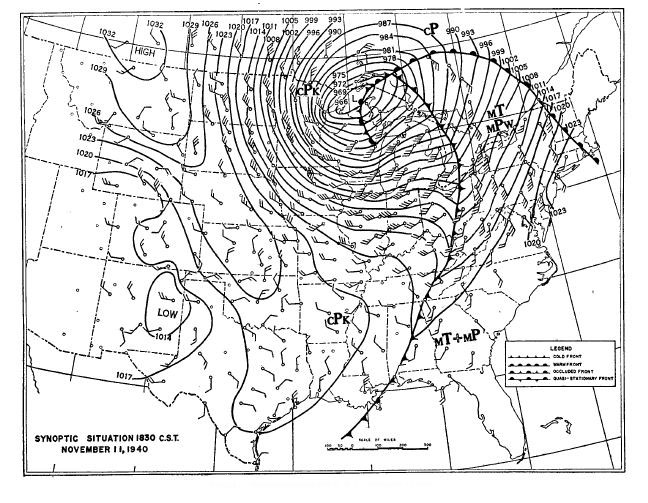

The central sea-level pressure of the storm dropped rapidly over the three days. On the morning of the 10th, it stood at about 995 mb (29.38 inches Hg) at its location in eastern Colorado/western Kansas. By midday, the storm center had not moved much but the pressure had dropped to 994 mb (29.36 inches Hg). By morning on the 11th, the low’s center had reached Iowa and dropped another 10 mb (0.3 inches Hg) to 984 mb (29.06 inches Hg). By the early evening of 11 November, the system lay over western Lake Superior and its pressure had dropped to 968 mb (28.59 inches Hg). Pressure readings that day of 967 mb (28.56 inches Hg) at Houghton, Michigan, 970 mb (28.65 inches Hg) at Duluth, Minnesota and 972 mb (28.71 inches Hg) at La Crosse, Wisconsin rank among the lowest sea-level pressure readings in the Upper Midwest. The storm’s rapid pressure drop of over 28 mb (0.83 inches Hg) from 1830 EST of the 10th to 1830 EST of the 11th puts it into the definition for a “bomb” storm: a pressure drop of 24 mb (0.71 inches Hg) or more in 24 hours. At its lowest, the central pressure for this storm stood at 956 mb (28.23 inches Hg), equivalent to what would be expected in a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Scale.

The Armistice Day Storm raged across six states before moving over Lake Superior and eventually into Northwestern Ontario: Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan and the waters of Lakes Superior, Michigan and Huron. Its influence extended even further east, bringing high winds and rain to the Ohio Valley and the eastern Great Lakes Erie and Ontario. Precipitation accumulation locally reached 2-3 inches (50-75 mm), while the area over which an inch or more (25 mm) fell extended to “hundreds of thousands of square miles” according the US Weather Bureau storm report, extending from the Plains states to the Appalachian Mountains and from the lower Mississippi Valley to the Canadian border.

Snow and freezing rain fell across the sections west of the storm path, being particularly heavy in Minnesota and western Iowa. In some areas of these states, freezing rain coated wires and trees with ice one-inch thick before turning to snow. Minneapolis received 16.2 inches of snow, which was then the greatest single storm snowfall in the city (and would stay so for another 40-plus years, until January 1982). Other climate stations in Minnesota reported 22 inches or more. Collegeville had 26.6 inches, and 20-foot (6.1 m) high drifts were reported near Willmar. The maximum snow accumulation in Iowa was 17 inches.

With the rain and snow, high winds swept across the tight pressure gradient associated with the storm. Duluth recorded a 5-minute sustained wind of 52 mph (83 km/h) while Minneapolis saw 38 mph (61 km/h) winds. To the east of the storm, the winds were even higher: Grand Rapids, Michigan hit 65 mph (104 km/h); Cleveland, Ohio, 59 mph (95 km/h); Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 54 mph (87 km/h); and Fort Wayne, Indiana, 53 mph (85 km/h).

|

|

|

On the Great Lakes, gales and high waves harried shipping and fishing boats, sinking a number of vessels (see below). The winds crossing Lake Michigan caused a 4.8 ft (1.46 m) drop in water level at Chicago and rise of 4-4.5 ft (1.2-1.4 m) at Beaver Island, Michigan, located in the extreme north of the lake. The lowering of the waters at Green Bay, Wisconsin caused the shutdown of a paper mill and a power plant. At Alpena, Michigan, the water level receded by about 2 feet (0.61 m). At Bay City, Michigan, the low water caused the water supply intake pipes to be exposed which caused a cessation in pumping of water into the reservoirs. The drop in water levels at Saginaw Bay forced the Consumers Power plant to be shut down. On the lower Detroit River, water levels fell by 4.5 feet (1.4 m) in reaction to the strong winds blowing across Lake Erie.

The majority of the losses of life and shipping occurred on Lake Michigan where three steamers were sunk, a number of car ferries grounded and many smaller vessels lost. In the opinion of veteran Captain Harold B. McCool, with over 40 years on the Lakes: “In my opinion, the storm was even more severe than the disastrous storm during the Fall [November] of 1913.” Although this storm was one of the most severe meteorologically on record on the Great Lakes, the loss of life (66 sailors and fishermen) was not as high as in other storms.

Death and destruction was not limited to the waters. A passenger train collided head on with a freight train in the raging blizzard outside the Watkins, Minnesota depot, resulting in two crewman deaths. In the blinding snow, the passenger train’s crew had missed a warning signal. Eyewitnesses recalled local residents forming a human chain to lead the passengers to safety in the howling blizzard. Adding to the surreal conditions, one train whistle jammed open and wailed with the wind long into the night until the steam finally ran out.

An interesting side bar story came out of the College of St Teresa in Winona, Minnesota. That evening, a young pianist finished his concert encore there with a piece called The Night Winds. News accounts of the concert note that within the concert hall the wind’s roar nearly drowned out the music. The performer was Walter Valentino Liberace of Milwaukee and we would later know him simply by his last name.

All across the region, property damage mounted. Roofs were blown off and miles of telephone and power lines were downed. Farmers lost stock and outbuildings. But the greatest hazard struck the duck hunters on local marshes.

It was duck hunting season. The storm hit on what we would call a three-day weekend as Armistice Day, a holiday, fell on Monday. As a result, many hunters that were hunting in marshes across the region were caught unaware by the storm— the last forecast for the area called for weather turning a little colder and flurries. The weather prior to the storm was rather mild and without an adequate warning of what was to come, many hunters were not dressed for extreme cold, and many wore only light jackets or heavy shirts. (The situation was reminiscent of the “Children’s Blizzard” of 1888 when people were caught unaware of a dangerous storm by unusually mild weather.)

A number of hunters were caught on boats on the edges of the Mississippi River, no match for the raging winds and waves, and were forced to weather the storm on small offshore islands. Norman Roloff recalled the day: “I recall it being quite warm. It was so warm when I rowed the skiff across [the Mississippi shoreline near Winona, Minnesota], I took my hunting jacket off, because it was actually that warm.” Thousands of ducks, perhaps pushed by the storm, passed overhead, and shotgun blasts echoed across the marshland as hunters reveled in the bounty.

|

|

However, in moments, the shirtsleeve weather became nasty: fast. One newspaper referred to the storm as “the winds of hell.” It blew many hunters in small boats out into the now-raging open waters. Caught in the rain and snow and howling winds, the ill-dressed hunters were no match for the conditions, and many drowned or froze to death. Others suffered through the storm as best they could. One hunter survived by cuddling up with his hunting dogs. Roloff was able to paddle back to the shore as the boat filled with water and struggle back with his companions into a nearby town.

In all, 38 duck hunters in Wisconsin and Minnesota were counted in the storm’s list of fatalities. Duck hunters accounted for half the number of dead in Minnesota.

Severe storms that rage across the Great Lakes in the autumn and early winter are often called “Furies” and may blow with hurricane force. The storm of 11 November 1940 ranks high in the pantheon of such Great Lake storms. The mariners on Lake Michigan felt its greatest wrath. The storm broke out on Lake Michigan during the late afternoon when southwest winds rose suddenly, attaining hurricane force. Many vessels along the western shore of Lake Michigan were pushed aground, including the Pere Marquette car ferry City of Flint 32.

The City of Flint 32, with a crew of 43 and two passengers, had not been able to make harbor in Ludington, Michigan during the raging storm and, after hitting the breakwaters, was beached about 300 yards (300 m) from shore. Her relief captain Jens Vevang ordered her scuttled in order to avoid pounding by the high waves. All those aboard rode out the storm and were rescued the following day. Days afterward, the car ferry was pulled from the beach and eventually returned to service until her retirement in 1967.

The crews aboard the freighters William B. Davock, Manna C. Minch, and Novadoc were not as fortunate. All three foundered and sank off Pentwater, near Ludington with losses of life numbering 33, 24, and 2, respectively. Novadoc ran aground at Juniper Beach and broke in two. The surviving members of its crew were rescued from the pilot house by the fishing tug Three Brothers.

Fishing tugs Indian and Richard H. and the motor cruiser Nancy Jane sank in the southern waters of Lake Michigan. A total of ten were lost from these vessels. A number of other vessels were driven ashore or onto reefs across Lake Michigan.

On Lake Superior, two lives were lost, both fishermen in Whitefish Bay. However, the rolling and heaving waters caused a number of automobiles to break loose and plunge overboard from the steamer Crescent City. The freighter Sparta grounded on rocks east of Munising, Michigan and was lost but all aboard survived the ordeal.

No fatalities or major vessels were lost on Lake Huron, perhaps because the winds blew off the Michigan shore. Many fishing boats, however, lost valuable netting but managed to find shelter during the storm. Conditions on Lake Huron were described by the master of the steamer Wyandotte, carrying 2700 tons of coal to Alpena, Michigan. He reported that: “The sea broke over her decks in solid sheets. The storm was of such fury that water actually poured into her smoke stack at times.” Usually capable of travelling at 11 knots (20 km/h), the Wyandotte could make no better headway than 2-3 knots (3.6-5 km/h), according the master.

All across the region, property damage mounted. Roofs were blown off and miles of telephone and power lines were downed. Damage estimates amounted to $2 million (1940 dollars, the equivalent buying power to $30.6 million in 2009). In all, the fatality count reached 154 across its path, including 49 in Minnesota, 13 in both Illinois and Wisconsin, 4 in Michigan and 66 on the Lakes.

Losses of turkeys, bound for Thanksgiving tables later in the month, on farms in Nebraska, Wisconsin, Minnesota and other states numbered over a million, with estimated value of over half a million dollars. Fifteen hundred cattle and 2000 sheep were reported killed in Iowa.

Because of this storm and one which hit the following spring, Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen and Congressman R. T. Buckler of Crookston both criticize the US Weather Bureau for the inadequate storm warnings and lack of facilities in the state to provide 24-hour forecasting operations. In letters to Secretary of Commerce Jesse Jones, they asked for changes and soon thereafter, Minnesota had a 24-hour forecast office and with larger staff.

As of 1 October 2010, the Armistice Day Blizzard ranked second on the Minnesota State Climatology Office’s Top Ten Weather Events of the 20th Century in that state. It also ranked second on NOAA’s list of top blizzards in the United States (Excluding the mountains of the West and lake-effect snows.) The storm also ranked as the top storm to hit the Central United States/Upper Great Lakes States. In late October 2010, as I was writing this piece, that all changed.

The Armistice Day storm (965 mb / 28.50 inches Hg) ranked first in the listing of lowest storm central pressure in the central United States until 26 October 2010 when the central pressure of a mammoth storm moving across the region broke this mark. At 4 PM (CDT) 26 October 2010, the central pressure of this new storm stood at 956.1 millibars (28.23 inches Hg) at nternational Falls, Minnesota, which sets a new benchmark for storms. This is also the lowest inland pressure (corrected to sea level) ever recorded in the interior United States.

|

Now AvailableThe Field Guide to Natural Phenomena: |

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Order Today from Amazon! | |

|

|

To Order in Canada: |

To Order in Canada: |