|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||

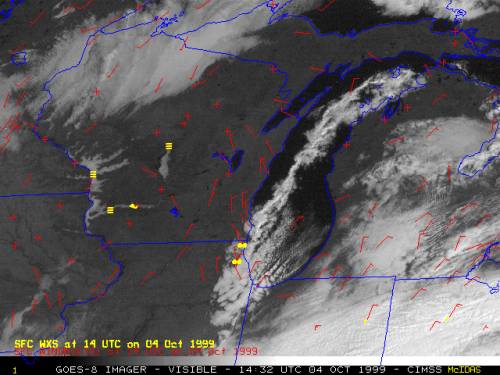

Lake Effect RainsIn the past, I have written about lake-effect snowfalls with particular emphasis on the Great Lakes Region. These snowfalls have had major impacts and unbelievable accumulations, particularly around Buffalo and upstate New York. Lake-effect snows, however, have a lesser known sibling: lake-effect rains. In general, lake-effect precipitation arises when cold air, passing for a sufficient distance over the relatively warm waters of a large lake, picks up moisture and heat and then precipitates the moisture out over the lake or along the downwind shore. Lake-effect rainfalls are spawned in a similar manner to lake-effect snows, with the biggest difference being the temperature of the overriding blast of cold air, which is cold enough to get the process moving, but warm enough in its lower layers so that the precipitation hitting the ground falls as rain rather than as snow. For the discussion, I will focus here also on the North American Great Lakes. The phenomenon, however, can be found downwind of any lake large enough to retain its summer heat well into the cold days of autumn and early winter. Each year as the first cold blasts of air descend from the polar regions, they move across waters of the Great Lakes that are substantially warmer than the cold air. When cold air traverses the lake's warm and moist surface-air, the surface air is lighter than the air above it, a condition known to meteorologists as convective instability, and starts to rise. How high it will rise, in part, depends on the temperature contrast between the surface air and that moving over it. Often, the layer above the lake is also conditionally unstable, meaning that a trigger is needed to start the convective process rolling toward precipitation formation. Usually for the rain events, this is provided by an approaching short wave and attendant surface trough of low pressure from the west.  A study of lake-effect rain events for Lake Erie by Pennsylvania State University meteorologists Todd J. Miner and J. M. Fritsch found, in contrast to most lake-effect snow events, the conditionally unstable layer for lake-effect rain events was much thicker, thus allowing for greater convective activity and often thunderstorm formation. As a result, the greatest number of lake-effect days with thunder around Lake Erie occurs from late September to mid-October when the layer of conditionally unstable air is much deeper. While October had the greatest number of lake-effect thunder events, September had the highest percentage of thunder per lake-effect rain event, over 40%. Higher relative humidity in the overriding air produces a more widespread cloud cover during lake-effect rain events compared to snow events. Clouds are also deeper than during snow events, leading analysts to suggest that the steering of lake-effect rains may come from a higher level than snow events. Miner and Fritsch suggest the mean 850-700 mb wind vector might be used to better determine the precipitation movement than the 850 mb wind used for snow movement. Whether the precipitation falls as rain or snow, depends on the temperature profile of the lower to middle troposphere. Since all lake-effect precipitation begins in the clouds as snow, the thermal profile between the precipitation layer and the surface ultimately determines whether precipitation reaches the ground as rain or snow. Thus, for rain events, the temperature of the boundary layer must exceed 0o C (32o F) through a sufficient depth to melt the snow to liquid rain.  NOAA GOES-8 visible imagery shows a lake-effect cloud plume over Lake Michigan |

|||||||||

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now Available in the US! |

The BC Weather Book: |