|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||

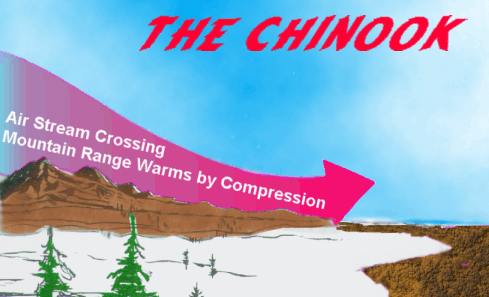

The ChinookThey flow off the mountain ridges, rushing winds that are very hot and very dry. Along the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains, they have been called "Snow Eaters" but today are more commonly known by their native American name: Chinook.  Such hot and dry winds descending mountain slopes are found around the world. Since they were first studied in the Alps, they are generically known by their local Alpine name: the Fohn winds (or Foehn, or more correctly Föhn winds). Fohn winds flow off mountain ridges, usually in the lee of the prevailing wind direction. In Libya, their local name is ghibli, while in Java they're called the koembang. From off the Andes, they blow as the puelche, or on the Argentinian pampas as the zonda. In North America, they have had several local names including the Santa Ana winds of California, but most of us know them as the chinook of the western Prairies and Plains regions. The fohn-wind family consists of winds that are warm and dry because their air has been warmed by compression as they flow over the mountain ranges and then down the leeward slopes. To describe to you how they typically form, I'll use the Canadian (Alberta) chinook as my example. From a global perspective, the prevailing wind regime, the Prevailing Westerlies — or just the Westerlies — blow across southern Canada from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic shore. We first pick them up approaching the Pacific coastline where in crossing the northern Pacific waters during the winter, they have picked up heat and moisture from the underlying ocean surface. When these relatively warm and very moist winds make landfall, they encounter the coastal mountain ranges of British Columbia, they are forced to rise over the mountain barrier on their trek eastward. As the flowing air mass rises toward the summit ridges, it cools until it eventually reaches its saturation temperature. At this time, its water vapour burden condenses into liquid water, first forming clouds, then precipitation. Much of that liquid, or frozen, water will eventually fall as prodigious amounts of rain or snow on the Coastal Ranges, watering the lush temperature rainforests for which the region is famous. Although the airmass cools by expansion as it rises over the mountains, it gains back a great deal of heat when its water vapour converts to liquid water — the latent heat of condensation which amounts to about 2.5 kilojoules or 597 calories per gram of water. (Additional heat — the latent heat of fusion — is released should the liquid water freeze to ice within the airmass.) By the time the airmass has traversed all of British Columbia's ranges, most of its water content has been lost through precipitation; however, a good portion of that released latent heat still remains in the airmass. When the airflow descends from the high ridges of the last mountain barrier, the Rockies, onto Alberta's high plains, it warms through the compression of the air, like the air in a bicycle pump when the plunger is pushed down. The airmass warms by about 9.8 Celsius degrees per 1000 metres of descent (5.4 Fahrenheit degrees per 1000 feet). Since many of the ridge lines in the Rockies are 3000 metres (10,000 feet) above sea-level and the Alberta plain is around 1000 metres (3300 ft), the air will warm by nearly 20 Celsius degrees (36 Fahrenheit degrees) in its descent. The air parcel is also very dry since it lost most of its initial moisture content crossing the mountains while gaining very little new moisture during its journey. This warm descending air is the chinook. The most impressive chinook winds blowing off the Rockies can reach speeds of between 65 and 95 km/h (40-60 mph) with gusts exceeding 160 km/h (100 mph). When blowing at those speeds, the chinook can tip railcars off the tracks and blow semi-trailer units off the road. Impressive as the chinook is as a wind, the temperature changes it brings can be astonishing, often as much as 20-25 Celsius degrees (36-45 F degrees) in an hour. The greatest chinook temperature jump ever recorded occurred on January 22, 1943, when a chinook shot the temperature in Spearfish, South Dakota, from a chilling minus 4oF (-20oC) at 7:30 AM to 47oF (8.3oC) just two minutes later! And, in Pincher Creek, Alberta, a chinook jacked the temperature 21 Celsius degrees (37.8 F degrees) in four minutes on January 6, 1966. No wonder, the chinook has the reputation its name "Snow Eater" engenders. The deadly-to-snow combination of high temperature and dry air rushing by at high speeds can literally remove a foot (30 cm) of snow in a few hours. And it may not just melt the snow but evaporate it as well, often all in one single process called sublimation, without leaving a liquid pool behind. The very dry air soaks up the liquid like a sponge, replenishing some of the water vapour lost in the mountain traverses. When, on February 25, 1986, a chinook descended on Lethbridge, Alberta with winds gusting to 166 km/h (104 mph), it fully removed a snow pack of 107 cm (42 inches) in depth in eight hours. Lethbridge was left with substantial wind damage and new lakes standing in the surrounding fields and pastures. Chinook winds may last from only a few hours to a few days, sometimes even persisting for several weeks. They can be welcome visitors during the winter, giving a respite to residents of the cold Prairies. But in other seasons, the searing dry winds can dessicate vegetation, raise soil into dust storms, and rapidly increase the danger of grass and forest fires. For many living under the chinook influence, its winds bring debilitating physical effects ranging from sleeplessness to anxiety and severe migraine headaches. Recent studies also suggest that Chinook winds rolling off the mountains can damage aircraft at cruising altitudes by generating turbulence powerful enough to rip an engine from a jet. The fire menace of fohn-type winds brings much worry in many areas particularly in the summer and autumn seasons. In the Canadian Prairies, concerns heighten over grass fire potential during dry periods. Similar worries arise each year between October and February for residents of Southern California. During this period, when the Santa Ana winds — a chinook cousin — blow, the dry chaparral country becomes a tinder box needing only a spark to touch off devastating wildfires. I'll leave you with a small table with some of the poetic names given locally to fohn winds around the world.

Learn More From These Relevant Books

|

|||||||||

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now Available in the US! |

The BC Weather Book: |