|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

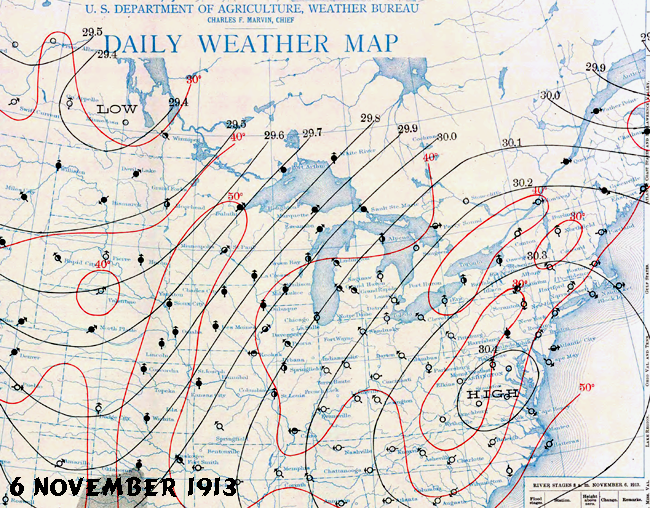

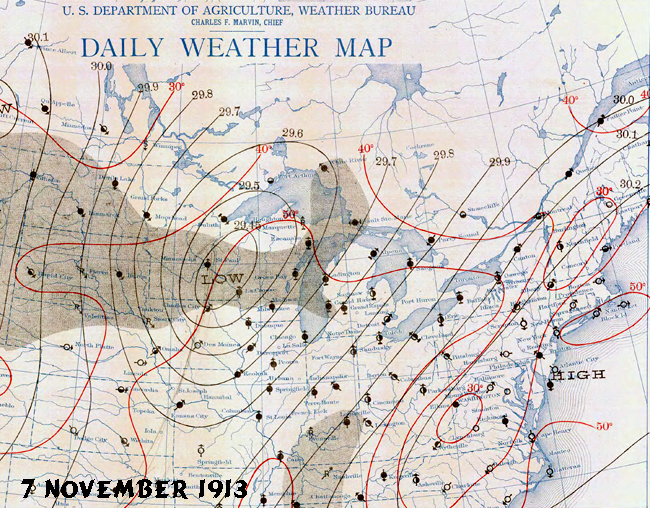

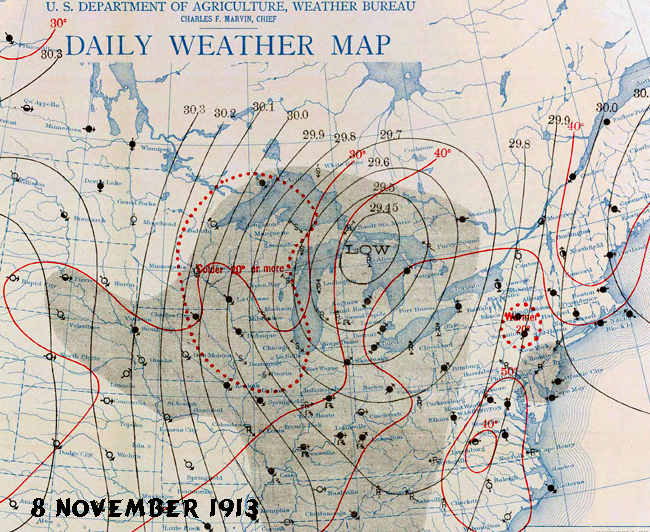

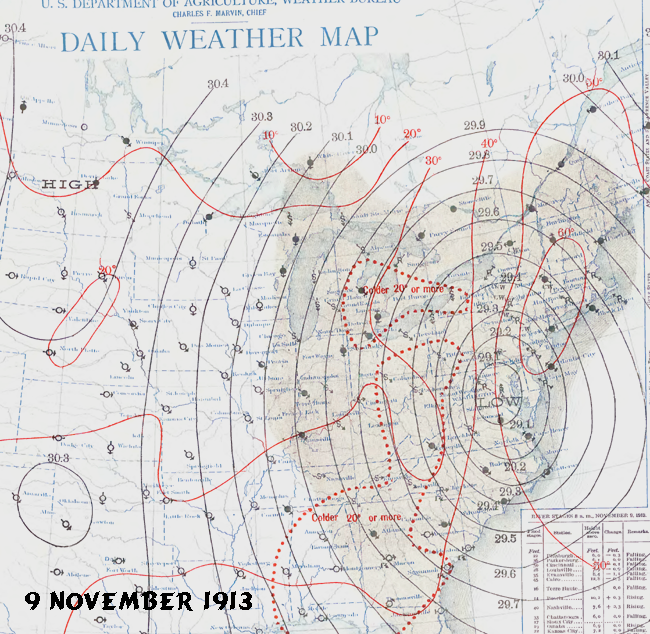

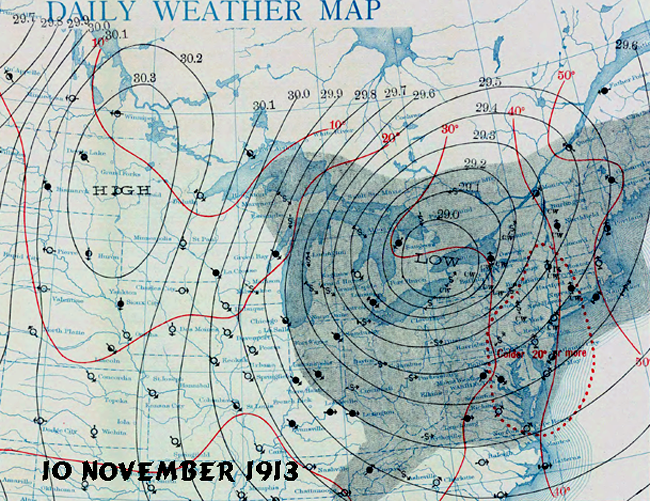

Weather Almanac for November 2013THE FRESHWATER FURY OF 1913Over the sixteen years that I have been writing this Almanac, I have often discussed the impact the Great Lakes have on autumn storms, and November is the month most known for those influences. The most infamous of these at the present is the November gales that took the ore carrier Edmund Fitzgerald to the bottom of Lake Superior. While the Fitzgerald storm is freshest in our collective memory, the deadliest of the 25 killer storms that have greeted November sailors on the five Lakes since 1847, occurred in November 1913, a century back this month. It has been given several names including the Freshwater Fury, the White Hurricane, and the Big Blow. From 7 to 12 November 1913, 19 lake vessels were destroyed and another 19 stranded, taking an estimated 235 lives in the storm's fury. Later accounting by the US Life-Saving Service suggested as many as 71 vessels were lost or severely damaged and 248 killed. (Though neither the accepted number or this one looked at deaths not related to the shipping industry.) On the night of 9 November, many large ships vanished without a trace. Most of the lost ships were sailing Lake Huron waters, but Lakes Superior, Michigan and Erie also saw sinkings and groundings.  Front Page Headline: Detroit News 13 November 1913The storm not only raged on the Lake waters, it struck as a blizzard in northern Ohio, eastern Michigan and southwestern Ontario. When the storm had ended, Cleveland, Ohio had snowdrifts 6 feet (2 m) high. The weather lore of the Great Lakes region of North America warms us of the storms of November, “the Witch of November” in the words of Canadian singer/songwriter Gordon Lightfoot in his ballad “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” Comes the StormNote: to facilitate discussion of the daily weather maps, I will use the Imperial units system in which they were produced. Similarly, to give the metric equivalent as I usually do would make for a messy text, and I have stuck with the Imperial system through out. Note too that at the time, weather front theory had not been developed; thus, the lack of fronts on the daily weather maps. What we now consider an active cold front was called a squall line and it differed from our present use of that term. In the discussion, I have roughly placed the position of the main cold front based on temperature and wind direction shifts as indicated in the data or the accounts. As with most of the harsh November storm on the Great Lakes, the Freshwater Fury began as a storm system that formed away from the Lakes before entering the basin. The Fury would be the child of two air masses: one unseasonable cold arctic air pulled down behind a low pressure region coming out of the Canadian Prairies. The second was warm humid air moving north from the Gulf of Mexico via the southeastern United States. As the cold air crossed the US Plains states, temperatures fell into the single digits Fahrenheit with drops of 20 Fahrenheit degrees over 24 hours in large areas as it moved south and east. When these two air masses collided over the relatively warm waters of the Great Lakes, the waters intensified the interaction, feeding energy into the storm, a process similar to that of a tropical storm moving over warmer ocean waters. Thursday 6 November: The morning weather map of Thursday 6 November shows the prairie low and the large high pressure system over the US Atlantic Coast with the warm air flow on its western (back) side. Over the Ohio Valley and eastern Great Lakes, temperatures had jumped by 8 to 18 F degrees over the previous 24 hours.  Daily Weather Map 6 November 1913Friday 7 November: On the following morning, a closed low appeared on the morning weather map over much of Minnesota with warm air funneling up into the central Lakes basin. Temperatures in northern Michigan stood that morning in the mid-50s (°F) while in the northern US Plains states, it was a few degrees above freezing. The winds began to pick up, and by later that morning, storm-warning flags began to be hoisted at the Lake Superior ports. A reported wind speed of 68 mph was observed at Houghton, Michigan on the southeast Superior shore. By 10 am, the storm warning flags were flying from Superior east to Lake Erie.  Daily Weather Map 7 November 1913With stormy conditions evolving over Superior, the weather far to the east saw windy conditions on the lakes, and balmy onshore. The warm air moving across Ohio reached 58°F at Toledo, and local vineyard workers took advantage of the pleasant temperatures to pick what portended to be a good grape harvest. But, at the western end of the lakes basin, conditions were deteriorating rapidly as what we now know as a cold front (but called a squall line at the time) roared across northern Minnesota. At noon, the front passed Duluth bringing gusty northwest winds in excess of 28 mph and rapidly falling temperatures. These northwesterly winds reached gale force (about 38 mph) on northern Lake Michigan and western Lake Superior. At Duluth, Minnesota they raged into the evening at speeds up to 60 mph. Following the frontal passage, temperatures took a precipitous fall and many vessels on Superior began to take a patina of ice on their decks and superstructures. By the end of the day, the heavy weather warning flags flew across all five Great Lakes and Georgian Bay. Saturday 8 November: The morning synoptic analysis showed a large low pressure cell centered over Lake Huron near Sault Ste Marie. Its extent covered all the Great Lakes. On Lake Superior, the steamer Cornell was sailing westward, east of Michigan's Keweenaw Peninsula, when it was struck by a massive wave around 1am, a wave that had outrun the squall line. Moments later, the vessel was hit with a northerly gale and blinding snow. Similar reports in vessel logbooks chronicle the windshift line as it passed across the upper Lakes.  Daily Weather Map 8 November 1913A quick look at that morning's map indicates that we today would drawn a cold front from west of Alpena, Michigan southwestward to north of St Louis, Missouri. The dotted area on the map below indicates the area from northern Ontario north of Lake Superior to central Illinois, and from Lake Michigan west to central Iowa where temperatures had dropped by 20 F degrees or more over the previous 24 hours. Winds behind the low descended from the north northwest bringing in the cold arctic air. As an example of the temperature drop, Green Bay, Wisconsin's temperature stood at 28°F at the time of the morning observation (8 am EST) a drop of 24 F deg from the previous morning. Detroit, Michigan began the day in the warm air sector, the morning temperature reported at 50°F, but as the day progressed, it fell reaching the lower 30s (°F) on gusty winds that shifted from the southwest to west around midnight. A complex weather pattern was developing over the United States with the storm over the Great Lakes and a budding low pressure cell over Virginia that was nearly unnoticeable on Saturday morning. With today's high density of weather observations, upper air data, satellite and radar to fuel sophisticated computer forecast models, forecasters would have had more concern over the situation. As it was, the Saturday morning forecast issued along with the weather map, indicated that the system would move through the Lakes, and, although colder conditions in the upper Lakes would prevail, the storminess would abate and Sunday would see fairer weather. But Mother Nature had other ideas. Sunday 9 November: Overnight, the small disturbance along the Atlantic coast exploded into a major nor'easter. By today's terminology, the development would be considered a weather bomb, explosive cyclogenesis, as the storm deepened about 0.9 inches of mercury (Hg) over 24 hours (0.72 inches Hg or more over 24 hours the criteria for a bomb). The blip from Saturday morning now had full cyclonic circulation with center over the Washington DC area at 29.1 inches Hg. This large storm system pulled in the low that had been over Lake Huron the previous day. As a result, the storm would move northward and slightly westward, deepening as the day moved on, its central pressure falling to 28.61 inches Hg over eastern Lake Erie near Erie, Pennsylvania.  Daily Weather Map 9 November 1913Temperatures across central Michigan, through southwestern Ontario and into western New York, as well as from Ohio down to the Gulf Coast, showed drops of 20 F degrees or more as the cold arctic air swept across the eastern US. Winds over the upper Lakes rushed out of the north to northwest at gale force, and after crossing the relatively warm waters of the Lakes began to produce lake-effect snows on the lee shores. The lake-effect snows were enhanced by the flow of moist air from the Atlantic on the upper right edge of the storm. In Cleveland, the northwest wind gusts hit 45 mph and heavy snow mixed with rain was beginning to accumulate in growing drifts. Unlike today, when weather data are taken hourly at major sites and much real-time information is available on demand, the Weather Bureau office in Washington would have to wait twelve hours for the next set of observations after the morning reports. Unfortunately, this storm system was evolving at a quicker pace. Over the Lakes, a cold “hurricane” was blowing and wind observations over the waters greatly exceeded those on land. Conditions worsen through the day over Lakes Huron and Erie. The weather observer at Toledo, Ohio noted: “today's snow and windstorm combined was more severe than any other previous one at the station.” Conditions in western Lake Superior did not improve as had been forecast. Gale force northwest winds continued to blow for a third straight day as the arctic high slid into the American Plains, sending cold air into the eastern low. At Port Huron, Michigan at the base of Lake Huron, winds continued to rise from 40 to 50 mph in the early afternoon, to 50 to 60 mph later that afternoon. The maximum wind speed, 62 mph, was recorded at 9:02 pm. In Detroit, the northwest winds increased through the day to 45 mph between 7 and 8 pm with an extreme gust of 70 mph recorded at 7:15 pm. A land station at Port Sanilac, Michigan observed gust between 75 and 80 mph. These land readings were likely much lower than those experienced on the open waters (due to reduced surface friction over the waters) of Lake Huron to the north. Captain S.A. Lyons of the J. H. Sheadle, in the waters north of Port Huron, reported that he estimated winds of 70 mph around 6 pm. Another vessel captain in the region off Harbor Beach, Michigan estimated the winds to be gusting to 90 mph. The day would be a deadly one for vessels on the Lakes as we shall later see. The conditions summed up in a report by the Lake Carriers Association following the Great Lakes freshwater fury placed the day into perspective: “No lake master can recall in all his experience a storm of such unprecedented violence with such rapid changes in the direction of the wind and its gusts of such fearful speed! Storms ordinarily of that velocity do not last over four or five hours, but this storm raged for sixteen hours continuously at an average velocity of sixty miles per hour, with frequent spurts of seventy and over. Obviously, with a wind of such long duration, the seas that were made were such that the lakes are not ordinarily acquainted with. The testimony of masters is that the waves were at least 35 feet high and followed each other in quick succession, three waves ordinarily coming one right after the other. They were considerably shorter than the waves that are formed by an ordinary gale. Being of such height and hurled with such force and such rapid succession, the ships must have been subjected to incredible punishment!” By midnight, Detroit measured 3 inches of snow while at the top of the St Clair River at Port Huron, the drifts reached 4-5 ft. Officially, Cleveland recorded 17.4 inches of snow in 24 hours, a new daily record. Toledo reported 27 inches on the ground at midnight. The barometer at locations around eastern Lake Erie took a precipitous drop between 8 am and 8 pm. At Buffalo, New York, the morning sea-level pressure stood at 29.52 inches Hg , a low value for most situations. But twelve hours later, it had fallen another 0.75 inches to 28.77 inches Hg. Earlier, the Queen City had measured a wind gust of 80 mph. Monday 10 November: The Monday morning weather map revealed a huge storm that encompassed most of the eastern United States and eastern Ontario. Cyclonically curved isobars stretched from off the New England coast to west of the Mississippi River; from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico. The storm's central closed isobar was drawn by Weather Bureau analysts at 29 inches Hg and encompassed eastern Lake Erie and western Lake Ontario and a good portion of southwestern Ontario. At Buffalo, New York, the morning reading stood at 28.96 inches Hg.  Daily Weather Map 10 November 1913At the morning observation, wind speeds at New York City and Block Island, Rhode Island measured 38 mph, speed similar to those still blasting the Upper Lakes: Marquette, Michigan (38 mph); Luddington, Michigan (36 mph); Duluth, Minnesota (34 mph). At Duluth a wind speed of48 mph has been observed at 3 am. On the shores of Lake Erie, winds blew at Buffalo at 60 mph. The arctic high to the west ridged from Lake Winnipeg to the Texas Gulf Coast and brought low temperatures in the teens Fahrenheit to the Dakotas and below freezing to the north Texas border. Duluth, Minnesota reported a low of 6°F. The cold air continued to flow southward across the Lakes region and wrapped around the cyclone across the Ohio Valley to the coast. Along the US Atlantic Coast from western New England to the Virginia—North Carolina border, the population shivered under temperatures 20 F degrees colder than the previous morning. Snow was reported as far south as Asheville, North Carolina. Cleveland and much of Ohio continued to accumulate heavy snows as strong winds raced over Lake Erie. Tuesday 11 November: The great storm finally began to pull away from the Great Lakes. The morning map placed the now-filling low centered over eastern Quebec and the Gulf of St Lawrence. Its influence still covering the eastern Great Lakes. To the west, the high pressure ridge extended from western Lake Superior southward to Alabama. Northerly winds still flowed over Michigan and eastern Ontario, and turned more westerly over Ohio and western New York.  Daily Weather Map 11 November 1913The storm dumped heavy snow on Ottawa, Ontario and affected shipping on the St Lawrence River around Montreal, Quebec. Marquette, Michigan was still being battered by strong northwesterly winds, a measurement of 48 mph in the morning hours. But at the observation hour, all Lake Superior onshore sites reported winds less than 20 mph. Winds in the upper lakes continued to abate as the day wore on. By the following morning (12 November), the dominant feature on the morning weather map for the Great Lakes region was the high pressure ridge that now centered along the southeast Atlantic coast over Georgia and the Carolinas. The Freshwater Fury had at last blow out. The Lakes Take Their TollThe storm of November 1913 stands as one of the deadliest on the Great Lakes on record. At least 19 lake vessels were destroyed and another 19 stranded, taking an estimate 235 lives of those aboard according to the accepted estimates. The US Life-Saving Service, however, reported the toll at 256 lives lost and 71 vessels lost or sufficiently damaged to require official notation. Of the wrecks, eight were large Lake freighters that sank in Lake Huron; many modern steel bulk freighters, 400 to 550 feet in length and up to nearly 8,000 gross tons. In this section, I will only summarize the devastation on the waters. For those seeking detailed accounts of the vessels plying the lakes at this time, I refer you to the well documented, detailed history of the storm by David G. Brown: White Hurricane: The Great Lakes Storm of 1913.  529-foot James Carruthers, the newest and strongest ship in the Canadian fleetFor many of the Great Lakes vessels, early November signified their last trip of the season before harsh winter weather and ice made sailing too hazardous. The “Gales of November” were already part of the mariner's lore. From 1847 to present, at least 25 November storms have been “killer storms”. For some, however, financial incentives may have pushed some captains to make one last run. As the storm built over the Lakes, ships' logs reported encountered high winds, high wave and in some cases freezing spray that coated decks in ice. Darkness, heavy spray and blowing snow all conspired to make conditions worse as low visibility made it nearly impossible to navigate. And when large storm raged over the Great Lakes, ships often ran out of room to run from the storms, a problem less often encountered by ocean going vessels. At the storm's peak, Lake masters reported waves reaching at least 35 feet in height and wind speeds at 50-60 mph with gusts as high as 100 mph. On Lake Huron when the winds shifted from northwest to northeast, winds battered the ships from one direction while waves pushed it from a much different one. The effect caused vessels to spin. On 9 November at the peak of the storm, an estimated dozen ships were lost on Lake Huron, some of which are yet to be found. Many others were grounded or damaged severely. (Few vessels had wireless radio at the time. When those lost disappeared is a matter of conjecture in most cases, based on other factors such as last sighting by another vessel.) In many cases, ships had not the engine power to fight the strong winds and waves and were pushed at the will of the elements, often toward shore where they were stranded in shallow waters or on the coastline. One of the more famous images from the storm came from the front page of the Detroit News on 13 November. It showed the bottom of a “mystery” lake vessel found floating on Lake Huron. From what could be seen of the wreck, no identification could be made. It was diver William Baker who several days later made the identification; it was the 524 ft carrier Charles S. Price.  Front Page Headline: Detroit News 13 November 1913The following tables list those ships known to be lost or foundered during the great storm.

Of those vessels lost, the wreck of the Regina was not found until 1986; the Wexford until 2000. To my knowledge, five other vessels have never been found including the Leafield , the Henry B. Smith, the James Carruthers, the Plymouth, and the Hydrus. There is also the possibility that other smaller vessels were also lost during the storm, as suggested by the US Life-Saving Service report, and never found. And so too, the loss of life on the lakes may have been higher than estimates. White Fury on LandThe fury of this great storm was not limited to the waters of the Great Lakes nor just the immediate shoreline. From eastern Minnesota to New York State and Quebec, the winds and precipitation battered the region, particularly in the know lake-effect snowbelts of the eastern Great Lakes. Nearly the whole state of Ohio staggered under six inches or more of snowfall, stretching as far south as the Ohio River. When the cold fronts swept through the Duluth, Minnesota/Superior, Wisconsin area on the western Lake Superior shoreline on Friday 7 November, the high winds whipped a fire that erupted in the boilerhouse of the Reiss Coal Company. It would destroy its Dock 3. Across the border in Superior, the blast of wind leveled three unloading rigs at the Boston Coal Dock. Ironically when the blast of winds behind the front hit Duluth, actor Walker Whiteside was preparing for the evening's production of The Typhoon. The gust estimated at 60 mph felled signs, fences and billboards and shattered window glass. By Monday morning, 10 November, the temperature in Duluth would drop to a frigid 6°F. When the northerly blast of cold air established itself over Lake Superior, heavy lake-effect snows began to fall across the northern shores of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. By Sunday afternoon (9 November), drifts measured in feet. Ishpeming, Michigan reported drifts of 6 to 9 ft. High waves pounding the shore on the Keweenaw Peninsula washed out the tracks of the South Shore railroad. Ironically, the previous summer, this area of track had been reinforced, particularly a trestle to “secure [it] against any storm that was likely to occur,” according to the Daily Mining Journal. The southern region of Lake Michigan, furthest from the center of the storm's fury, was not unaffected. Though winds did not reach the fury of those on the other lake, the wind's fetch ran the length of the lake, and sent damaging waves to Chicago, Illinois and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The Milwaukee harbor lost the entire south breakwater and much of the surrounding South Park lands to the ravages of the pounding waves.  Wave breaking on the shore of Lake Michigan by Lincoln Park |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now AvailableThe Field Guide to Natural Phenomena: |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

Now |

The BC Weather Book: |