|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Weather Almanac for March 2013AUSTRALIAN CYCLONES

When tropical storms impacting Australia reach what we in North America would call tropical storms and hurricanes, they are known as cyclones. When Henry Piddington first introduced the term cyclone to the weather language around 1840, he was making particular reference to the severe tropical storms that raged across the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. The word later was generalized to mean any organized low pressure system with winds circulating around the region of lowest pressure, and at one time also was a term for tornado in the US Plains (remember the Kansas cyclone of Wizard of Oz fame). However, herein, when I use the term cyclone, I am referring to a hurricane-type storm. An Australian cyclone shares all the characteristics and life cycle with its cousins the hurricane and typhoon in the Northern Hemisphere except, of course, that its winds blow in a clockwise direction around the low pressure eye (due to the reversal of the Coriolis force as we move south of the equator), and the storms steer southward rather than northward moving heat, moisture and energy from the equatorial regions toward the south polar regions. Southern hemisphere tropical storms, of course, form on the southern side of the equatorial zone. As with northern tropical storms, those of the south form over warm tropical waters whose water temperatures are at least 26.5°C (79.7°F) and no closer than 5 degrees latitude from the equator so that the Coriolis force can be effective in starting the spin.  Distribution of Tropical Cyclones |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australian Name | Australian Severity Category | Australian Category Limits Wind Speed / Gusts (km/h) |

US Name* | US Saffir-Simpson Category Scale* |

| Tropical low [or tropical storm] | NA | < 62 | Tropical depression | NA |

| Tropical cyclone | 1 | 62-88 Gusts < 125 |

Tropical storm | NA |

| Tropical cyclone | 2 | 89-117 Gusts 125 - 164 |

Tropical storm | NA |

| Severe tropical cyclone | 3 | ≥118 Gusts 165 - 224 |

Hurricane | 1 |

| Severe tropical cyclone | 4 | ≥118 Gusts 225 - 279 |

Hurricane | 2 - 3 |

| Severe tropical cyclone | 5 | ≥118 Gusts ≥280 |

Hurricane | 4 - 5 |

*Note that the USA uses 1-minute wind averages, which are generally greater than 10-minute wind averages used elsewhere in the world – hence their intensity definitions (wind strengths) will differ by about 10%. (Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology)

The damage descriptors for the Australian Categories are as follows:

(Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology)

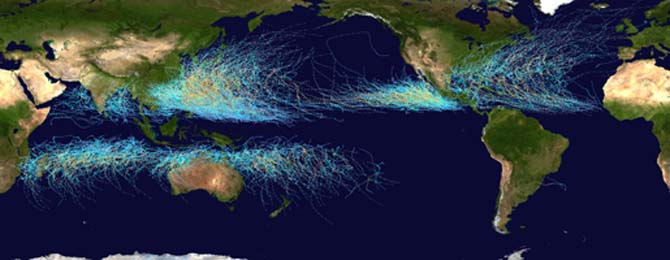

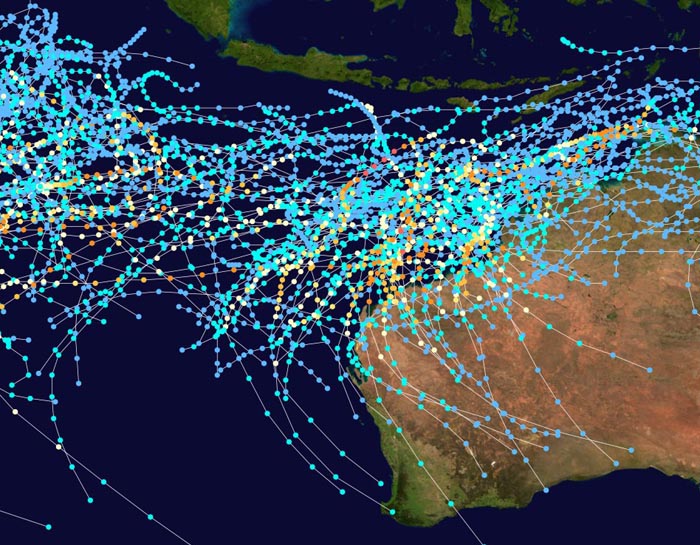

Tropical storms (used here in the more standard global definition) which impact Australia fall within two zones in the global tropical storm picture as seen in the maps below. The Australia Southwest Pacific zone on average sees 9 tropical storms, of which 4.8 become cyclones and 1.9 are severe(A-Category 3 or higher). In the South Indian Ocean zone, the average figures show 20.6 tropical storms, 10.3 cyclone with 4.3 severe. Most arise during the November to April period, but some storms may form during the southern winter in the Indian Ocean basin, though they seldom affect Australia.

|

Global Distribution of Tropical Storms: |

|

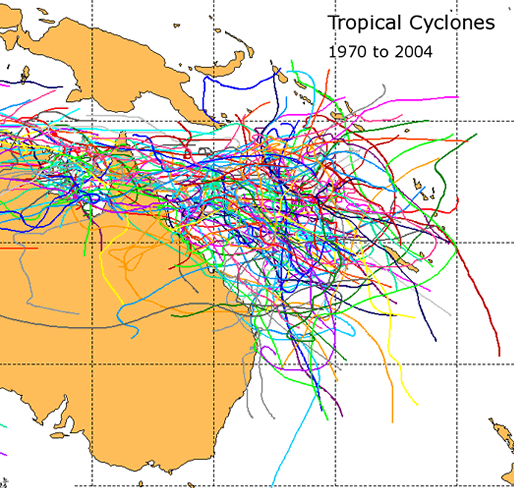

Close-up of Distribution of Tropical Storms |

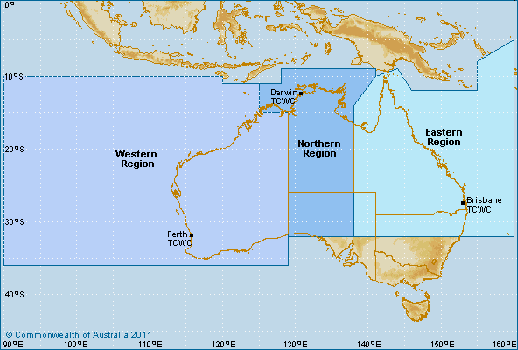

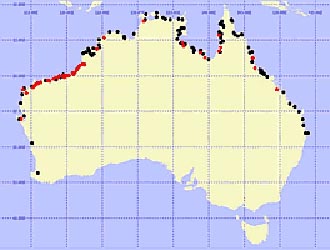

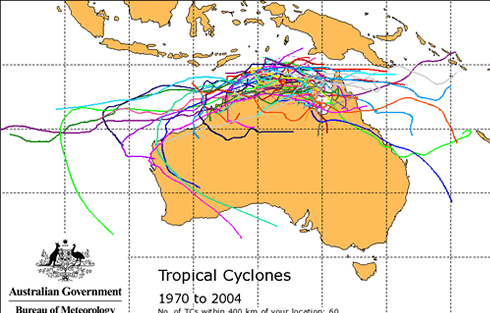

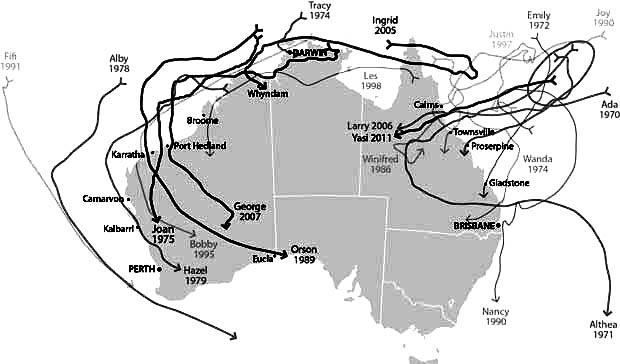

The following map shows the extent of the region surrounding Australia from which cyclones move toward the nation's coast. It is in these zones that the Australian Bureau of Meteorology Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre (TCWC) has jurisdiction for the tracking and forecasting of tropical storms and the issuance of storm warnings. The region is divided into three local centres which have jurisdiction for the West (Perth), North (Darwin) and East (Brisbane) subregions. Beside it lies a map showing the location of tropical cyclone crossings around the Australian continent over the climatological record from 1970 to 2008 seasons. Though the season “officially” runs from November to April, few cyclones arise in November that affect the continent.

|

|

Areas of Responsibility for |

Location of Tropical Cyclone Coastal Crossings |

The northern coast of Australia is closest to the spawning waters of most cyclones which strike Australia. This has both advantages and disadvantages for the region as the storms often do not have time to intensify into severe cyclones before hitting the continent, but the advance warning time is often quite short. Most of these storms hit the northern coasts of Western Australia, Northern Territory and Queensland with a slight bias toward the Western Australia coast.

According to TCWC, the climate record shows about thirteen cyclones form in the Australian region (from 90-160° E) each cyclone season. On average, 6-7 of these become severe (A-Category 3 or higher), meaning they reach levels similar to a hurricane designation on the American Saffir-Simpson Scale. Approximately half of the cyclones form in the western part of this basin and about a quarter of those may impact the state of Western Australia. Cyclones forming in the eastern basin also have a one in four chance of making landfall whereas those forming in the northern basin have an 80 percent chance of making landfall.

|

Tracks of Cyclones Affecting Western Australia: 1970-2008 |

|

|

Tracks of Cyclones Affecting the Northern Region |

Tracks of Cyclones Affecting the Eastern Region of Australia: 1970-2004 |

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology Tropical Cyclone Warning Centres keep track of tropical storms forming in the region surrounding their nation and as well have greater responsibilities for water outside their national jurisdiction. The TCWC will issue watches and warnings where appropriate during the life of a tropical storm/cyclone. The following definitions and details are quoted from their web pages.

The issuance of public notifications starts with these two basic advices. “Tropical Cyclone Advices are issued whenever a tropical cyclone is expected to cause winds in excess of 62 km/h (gale force) over land in Australia. A tropical cyclone advice may be a watch and/or a warning, depending on when and where the gales are expected to develop.

Tropical cyclone watch: Issued if a cyclone is expected to affect coastal communities within 48 hours, but not expected within 24 hours.Tropical cyclone warning: Issued if a cyclone is affecting or is expected to affect coastal communities within 24 hours. |

“Each advice issued for a particular cyclone will be numbered sequentially, starting at number 1 for the first advice. A tropical cyclone advice may contain a combined watch and warning, that is it will provide information on the area under watch status and the area under warning status.”

“Each Tropical Cyclone Advice will consist of the following information: The area covered by a cyclone watch and area covered by a cyclone warning The cyclone name The intensity [A-]category of the cyclone (1 - weak to 5 - strong) The latest observed location of the cyclone centre The central pressure of the cyclone (warning only) The distance of the cyclone to significant locations The expected or recent movement of the cyclone Range of destructive winds Maximum wind gusts Advisory statements on actions to be taken to mitigate the effects of the cyclone (note this is issued separately for the N[orthern ]T[erritory] and Kimberley) The issue time for the next warning

The TCWC is one of the global tropical storm warning centres, part of the World Meteorological Organizations Tropical Cyclone Program. As such, it provides services to regions outside its national jurisdiction. The Darwin Centre provides warning services for the sea area to the north of Australia. The Perth Centre issues tropical cyclone advices for Cocos and Christmas Islands.

Summaries of previous tropical cyclones with their paths can be found on the Australian Bureau of Meteorology website.

There are some historians who ascribe the practice of giving human names to storms as beginning in Australia (see Name that Storm for more) when Clement Wragge, an Australian meteorologist began giving women's names to tropical storms before the end of the l9th century. (Wragge also named severe non-tropical storms affecting Australia after men, usually local politicians he disliked.)

The TCWC has the charge for naming of cyclones within its jurisdiction under the auspices of the World Meteorological Organization. Their list includes 104 names, which since a change in protocol for the 2008/9 season replaced the previous three list rotation.

The TCWC states: “The name of a new tropical cyclone is usually selected from this list of names. If a named cyclone moves into the Australian region from another country's zone of responsibility, the name assigned by that other country will be retained. The names are normally chosen in sequence, when the list is exhausted, we return to the start of the list.”

The list currently contains the following names. Mitchell was the starting point for the 2012-13 cyclone season.

| Australian Region Tropical Cyclone Names | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Anika | Anthony | Alessia | Alfred | Ann |

| B | Billy | Bianca | Bruce | Blanche | Blake |

| C | Charlotte | Courtney | Christine | Caleb | Claudia |

| D | Dominic | Dianne | Dylan | Debbie | Damien |

| E | Ellie | Errol | Edna | Ernie | Esther |

| F | Freddy | Fina | Fletcher | Frances | Ferdinand |

| G | Gabrielle | Grant | Gillian | Greg | Gretel |

| H | Herman | Hayley | Hadi | Hilda | Harold |

| I | Ilsa | Iggy | Ita | Ira | Imogen |

| J | Jasper | Jenna | Jack | Joyce | Joshua |

| K | Kirrily | Koji | Kate | Kelvin | Kimi |

| L | Lincoln | Luana | Lam | Linda | Lucas |

| M | Megan | Mitchell | Marcia | Marcus | Marian |

| N | Neville | Narelle | Nathan | Nora | Noah |

| O | Olga | Oswald | Olwyn | Owen | Odette |

| PQ | Paul | Peta | Quang | Penny | Paddy |

| R | Robyn | Rusty | Raquel | Riley | Ruby |

| S | Sean | Sandra | Stan | Savannah | Seth |

| T | Tasha | Tim | Tatjana | Trevor | Tiffany |

| UV | Vince | Victoria | Uriah | Veronica | Vernon |

| WXYZ | Zelia | Zane | Yvette | Wallace | |

They use the list under the following set of guidelines.

The naming of Australian cyclones officially began in the 1963-64 cyclone season. Since then, 113 tropical cyclone names have been retired as of the 2010-11 season, with the decade of the 1990s accounting for 44 of the total. Cyclone Flora, a December 1964, A-Category 3 storm that struck Queensland and the Northern Territory, became the first storm in the Australian region to have its name retired. A list of all retired names can be found on Wikipedia.

The region of Australia most prone to cyclone impacts as well as the most likely to have a severe one is Western Australia, particularly the northwest section between the communities of Broome and Exmouth. Over the climate period 1970 to 2002, 34 of 42 severe cyclones to cross the coastline of Australia did so in Western Australia, about one of the 2.2 per year, and most struck between Broome and Exmouth.

At the start of the cyclone season, the most likely area to be affected by tropical cyclones is the Kimberley and Pilbara coastline. Later in the season, the area threatened extends further south including the west coast of the continent. The chance of experiencing an intense A-Category 4 or 5 cyclone is highest in March and April.

The earliest cyclone known to impact the northwest coast in a season was on 19 November 1910 when the storm's eye passed over Broome. The latest known cyclone was Cyclone Herbie that formed near Cocos Islands and passed over Shark Bay on 21 May 1988. One of Australia's most severe cyclones since the 1960s was Cyclone Sam, which killed 163 people along the coast of Western Australia and the Northern Territory during the period 28 November–10 December, 2000.

Cyclones Gwenda (1999) and Inigo (2003) both had minimum central pressures of 900 hPa (mb) making them two of the most intense low pressure systems ever recorded in the Southern Hemisphere.

Many of Australia's A-Category 5 cyclones have struck the Western Australia state since 1960. These include Joan (1975); Orson (1989); Ian (1992); Vance (1999); Gwenda (1999); John (1999); Rosita (2000); Chris (2001); Inigo (2003); Fay (2004); Ingrid (2005); Glenda (2006); George (2007); and Laurence (2009).

The responsibility for cyclones in this area, known as the Western Region, is handled through the Perth Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre.

The coast of the Northern Territory sits closest to the cyclone spawning waters in the Arafura and Timor Seas. Those cyclones that form there strike the Gulf of Carpentaria region of the Territory twice a year on average, while about one per annum will hit the Arafura and Timor Seas coastline. More than half of the cyclones born in the waters off the Northern Territory move either southwest or southeast into adjoining regions. The Northern Territory will experience on average 7.7 days each year under cyclone weather.

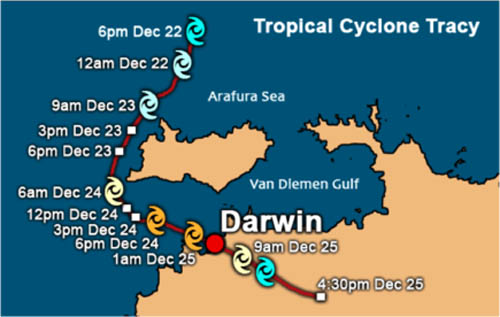

Many of Australia's most damaging and costly cyclones have had their greatest impact on the Northern Territory. One of the most infamous of these storms was the A-Category 4 cyclone Tracy which struck Darwin on Christmas Eve, 1974. Tracy inflicted widespread destruction across the city, severely damaging or destroying the majority of Darwin's buildings at an estimated cost of over A$ 3.5 billion to rebuild. Winds blew at speeds of over 217 km/h (136 mph) while torrential rain flooded the city. The storm killed 65 people, 49 on land, 16 at sea.

|

|

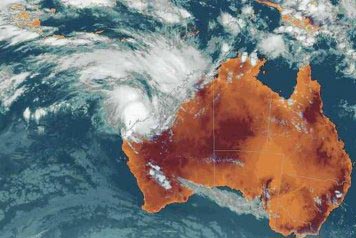

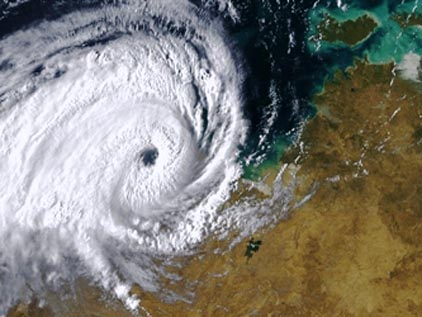

Satellite Image of Cyclone Tracy |

Path of Cyclone Tracy |

A-Category 5 cyclones to strike the Northern Territory since 1960 include: Kathy (1984); Thelma (1997); Vance (1999); Erica (2003); Fay (2004); Ingrid (2005); Monica (2006); and Laurence (2009).

The responsibility for cyclones in this area, known as the Northern Region, is handled through the Darwin Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre.

Queensland is located in the Eastern Region of Australia's Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre group. Its headquarters are located in Brisbane, about halfway down the eastern Australia Coast.

On average 4.7 tropical cyclones per year impact Queensland. Those since 1960 that have been rated as A-Category 5 storms include: Kathy (1984); Erica (2003); Ingrid (2005); Larry (2006); Monica (2006); and Hamish (2009); Yashi (2011). In addition, earlier cyclones rated as A-Category 5 to hit the state include Mahina (1899) and Innisfail (1918). Major pre-1960 storms to strike the Queensland region of the Gulf of Carpentaria and not rated include the 1887 Burketown cyclone, the 1923 Douglas Mawson cyclone, the 1936 Mornington Island cyclone; and the 1948 Bentick Island cyclone.

Cyclone Yasi was one of the greatest cyclones to hit Australia in the past half century. The storm killed 87 people and caused A$977 million in damage. It struck on 3 February 2011 crossing the coast near Mission Beach, about 128 km (85 miles) south of Cairns with a five-metre (17 ft) storm surge and peak winds estimated at 205 km/h (128 mph) and gusts at 285 km/h (178 mph). A barograph at the Tully Sugar Mill recorded a minimum pressure of 929 hPa (mb) as the eye passed .Yasi was such a large, intense storm (a massive 1,450 km (906 miles) in diameter), that it moved inland and did not dissipate until it had reached Alice Springs in the heart of the continent. The storm dropped torrential rains across the region with peak accumulations at South Mission Beach 471mm (18.5 inches); and Hawkins Creek, 464mm (18.3 inches).

It is well established that eastern Australian cyclones have a relationship with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) peaking (twice the number as occur in El Niño years) in years when the ENSO is in the La Niña phase when warmer waters are found off northern Australia.

Tropical cyclones do not often strike down the eastern Australia coast as far south as the State of New South Wales (NSW), but they do occur. Some move inland directly off the ocean waters while others impact NSW after entering Queensland in the Gulf of Carpentaria and moving southeastward into the State. Flooding is often the main concern and the prime cause of death and destruction in New South Wales. Winds and storm surges must also be considered when cyclones skirt the coast without making landfall. Cyclone Yali in March 1998 generated erosive 5.0 to 9.7 m (16-32 ft) waves along the NSW shore as it passed parallel to the coast some 500 km (312 miles) offshore. Similarly, Cyclone Pam in February 1974 brought severe wave action and beach erosion to Sydney beaches.

The area is under the Brisbane office of the Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre.

Among the strongest storms to impact New South Wales have been A-Category 5 storm Laurence (2009); and A-Category 3 storms Simon (1980), and Violet (1995). Earlier storms of note included an unnamed storm in mid-January 1950 rated as a A-Category 1 storm that killed seven in the state, and established the lowest barometric pressure ever recorded in Sydney: 988 hPa (mb).

|

Now AvailableThe Field Guide to Natural Phenomena: |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

Now |

The BC Weather Book: |