|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Weather Almanac for January 2012THE KNICKERBOCKER STORM 1922

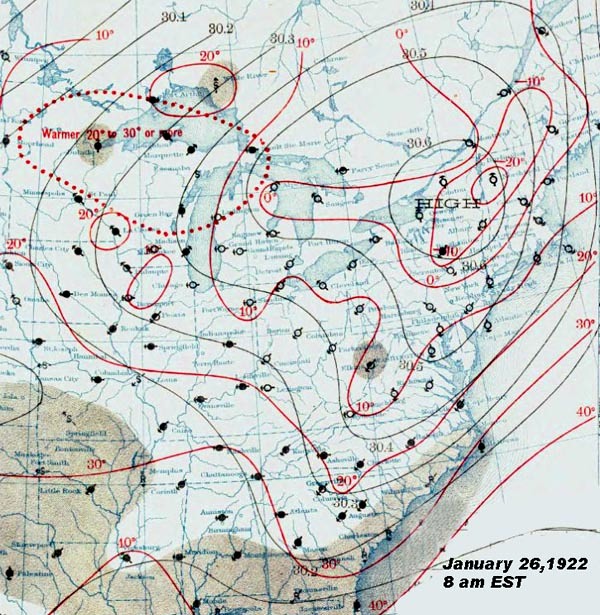

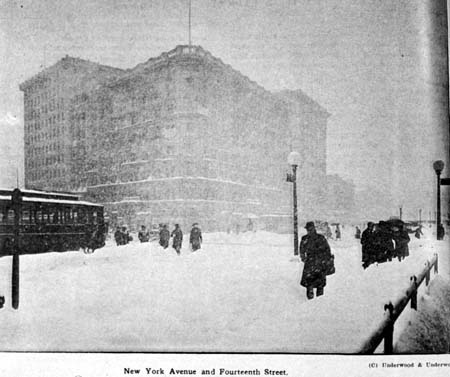

Before the StormThe District of Columbia and surrounding region generally experiences a winter climate that is milder than that further up the Atlantic coast, but can have its strong bursts of snow and cold. As the historic record shows, since the inauguration date was moved to January, several presidential inaugurations have been marred by snow and cold. And who will forget the infamous "Snowmageddon" and "Snowmageddon 2.0" storms of February 2010. But prior to those storms, the Knickerbocker storm of 1922 held a special place in Washington DC’s weather annals. In the days preceding the storm of 27 January 1922, Washington weather was mild early in the month and again during the week prior (20 January) to the storm when the high temperature reached 53°F (11.7°C).  Weather Map for 26 January 1922, 8 am EST |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

F Street, Washington's busiest thoroughfare |

Pennsylvania Avenue, near State, War, and Navy Building. |

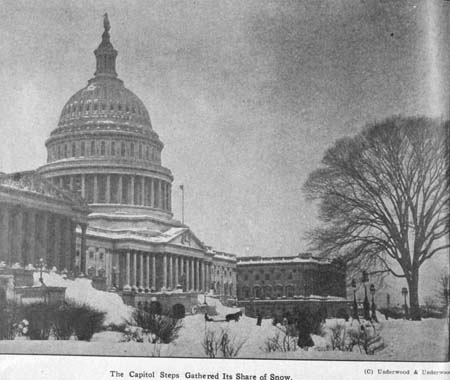

However, it was not the biggest ever experienced in the area. That honor belonged to the so-named Washington and Jefferson Snowstorm of January 1772 when 36 inches (0.91 m) of snow fell on the region. (The storm, which occurred 150 years to the day before the Knickerbocker storm, was so named based on the writings and observations of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson at their nearby plantations.) The daily accumulation on the 28th measured a record 21 inches (53 cm), and over a 24-hour period within the 27th and 28th tallied 25 inches (63.5 cm). For the in-city observation site, the single day, two-day, and three-day (storm) snowfall records all remain at those set during this storm. The storm (and two-day) records fell (32.4 inches (82.3 cm) total) at Washington’s Dulles International Airport during the famed “Snowmageddon” storm of February 2010. (And to add further insult to the Capitol, "Snowmageddon 2.0" struck four days later.) The daily snowfall at Dulles on 11 February 1983 of 22.5 inches (57.1 cm) also exceeded that of the daily snowfall in 1922.

|

|

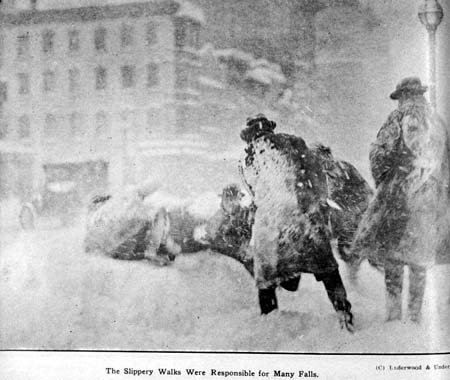

Slippery walks were responsible for many falls |

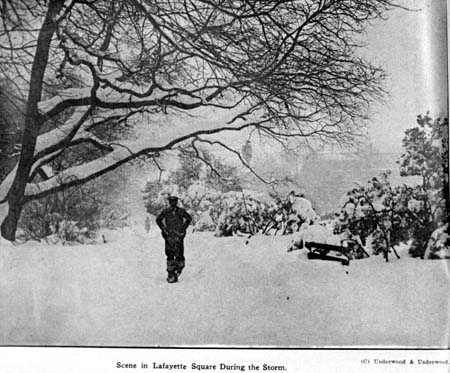

Lafayette Square during the "Knickerbocker" storm. |

In nearby Baltimore, the final snow tally measured 26.5 inches (67.3 cm), the greatest storm accumulation there since records began in 1872. The Knickerbocker storm total would not be exceeded until 1996, and again in 2003. However, the single-day total of 23.3 inches (59.2 cm) and the two-day total — 26.3 inches (66.8 cm) — still stand. Richmond, Virginia recorded 19 inches (48 cm) during the storm.

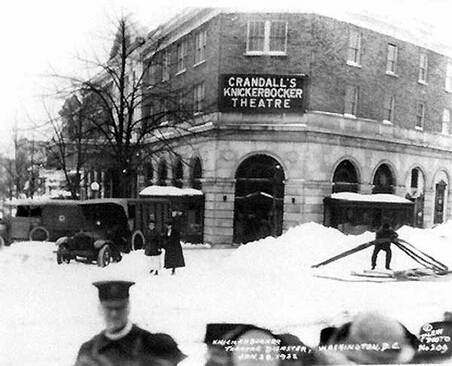

The storm-defining event occurred on Saturday evening (28 January) at Crandall’s Knickerbocker Theater. The theater owned by Harry Crandall was the largest and most modern movie house in Washington at the time. Opened in 1917, it was located at the corner of 18th Street NW and Columbia Road, and held 1700 patrons.

That evening, patrons, who had braved the raging storm outside to reach the theater, were awaiting the second showing of the silent movie Get Rich Quick Wallingford, starring George M. Cohan (and featuring the debut of comedian Jimmy Durante). Saturday night was “Comedy” night at the Knickerbocker, and a very popular attraction that enticed many to leave the comforts of home that stormy evening. The second showing of the evening was about to begin, and patrons were still filing into their seats when disaster struck.

At approximately 9 pm — plus or minus a couple minutes to the recollection of one survivor — the weight of the snow accumulated on the building’s flat roof caused it to collapse. Some survivors recalled a hissing sound filling the hall just prior to the ceiling splitting down its center. Others said there was no warning. As it split with a frightening roar, the cave-in brought down the cement balcony, its seats and a portion of the brick wall onto the main floor. Dozens were buried in the collapse.

Those fortunate enough to have not been buried raced for any exit they could find. Others called for missing friends and family lost in the rubble and rising dust and snow. One newspaper scribe, a veteran reporter of the devastation of World War I, likened the twisted steel, broken timbers and cracked cement to be “as grim as any ruin in the war-swept area of France or Belgium.”

The chaos of the initial scene lessened with the arrival of police and firemen who organized the rescue operation. Heavy equipment was brought in and by midnight, a crew of 200 had assembled. The number swelled to 600 volunteers and 200 police by 2:30 am. The shouts of rescue workers mixed with cries of anguish from those still buried under the wreckage of twisted steel, splintered timber and crumbled masonry that covered the floor of the theater. Once rescuers had cut through the heavy wire screening that held the ceiling’s plaster, they still had to cut through the cement of the balcony to reach those trapped under the debris on the main floor.

All local hospital rooms quickly filled with the injured, as did many hotels who opened their doors to the victims. Nearby homes and shops joined in assisting the injured and the escaped as well as the rescue workers. The rescue effort was not completed until mid-afternoon Sunday. In total, 98 patrons died and another 133 were injured. One of the dead was former Pennsylvania Congressman Andrew Jackson Barchfeld.

The wreckage of the Knickerbocker Theater was razed and a new theater was built on the site: the Ambassador Theater, also owned by Harry Crandall. The tragedy could be attributed to two more deaths in the coming years. The theater’s architect Reginald Geare would get no further work after the collapse, although official inquiries exonerated him of any fault for the collapse. He took his own life in 1927, despondent at the loss of his career. A similar fate claimed theater owner Harry M. Crandall who committed suicide in 1937.

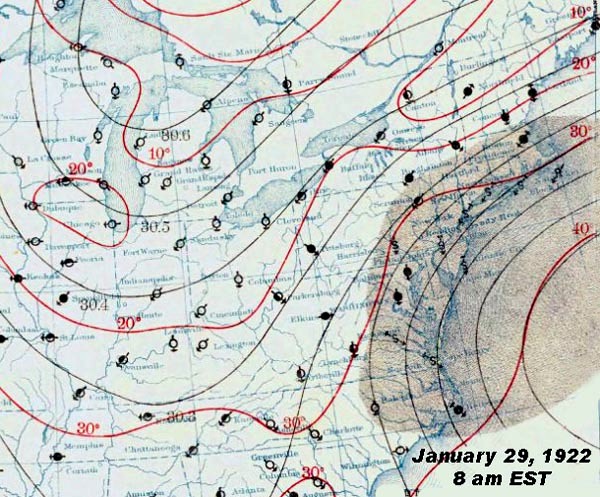

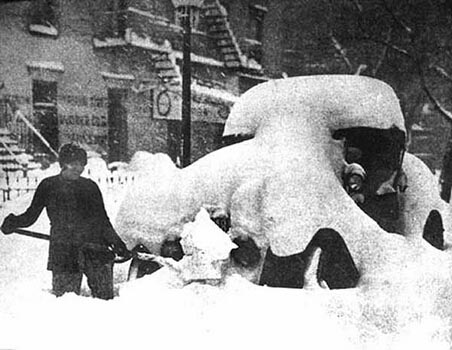

After burying Washington and Baltimore, the Knickerbocker storm moved northeastward, further out to sea. By the morning of the 29th, although it lay well east of Chesapeake Bay, it continued to pump moist air and strong winds into the Atlantic Coast from New Jersey north to Massachusetts. The storm’s slow movement allowed snowfall accumulations to pile to significant depth north of the DelMarVa region. The fallen snow accumulated to as much as 3 feet (91 cm) along the rail lines between Washington and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with gale-force winds building drifts as high as 16 feet (4.9 m). Atlantic City, New Jersey, Philadelphia, and New York City all received over an inch (250 mm) of precipitation (water equivalent) between 8 am, 28 January and 8 am, 29 January.

The storm stopped all rail and road traffic into and out of Washington for several days. Analysis of the extent of the storm indicated that approximately 22,400 square miles (58,000 km²) of the US Atlantic coastal states had snow accumulation of 20 inches (51 cm) or more, that affected around one million people. The area covered by 10 inches (25 cm) of snow was 62, 300 square miles (161,300 km²) and affected 26 million people.

|

|

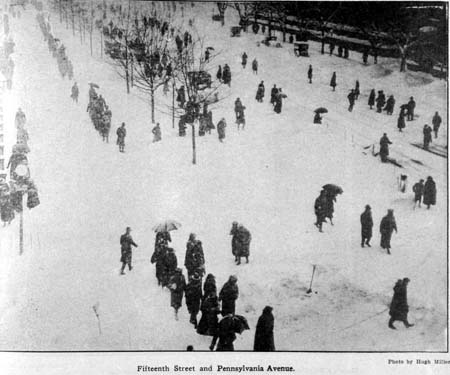

Pedestrian Traffic on Fifteenth St and Pennsylvania Ave. |

The Capitol steps gathered its share of snow. |

In the storm’s wake, Washington was paralyzed by the snow for several days. On Saturday, only 49 Senators and a handful of Representatives answered roll call, and Congress was soon adjourned. Only those Government workers who could walk to work managed to make it in, and several important committees meetings were cancelled.

|

Now AvailableThe Field Guide to Natural Phenomena: |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

Now |

The BC Weather Book: |