|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Weather Almanac for February 2010PLAYING THROUGH WINTER ON SNOW AND ICE:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Bone ice skate, c.1200 |

Medieval ice skates |

Wooden ice skate |

A 12th Century account written by William Fitzstephen, then secretary to England’s Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Beckett, describes skating thus:

“... when the great fenne or moore (which watereth the walles of the citie on the North side) is frozen, many young men play upon the yce, some striding as wide as they may, doe slide swiftly... some tye bones to their feete, and under their heeles, and shoving themselves by a little picked staffe, doe slide as swiftly as birde flyeth in the aire, or an arrow out of a crossbow.”

Technically, such skates merely glided upon the ice rather than “skated” on it. True skating occurs when the skates cut into the ice, and it is to the Dutch that we owe much of the next developmental stage of skating. Around the 14th Century, the Dutch began skating on wooden platform skates with flat iron bottom runners, which were tied to the shoes with leather straps. The action of skating was quite different from modern skating. Woodcuts from the 1500s show skaters on bone skates propelling themselves with a stick pushed between the legs to help pick up speed, a technique probably taken from skiing.

Poles became unnecessary when the Dutch took the next evolutionary step and added a narrow metal, double-edged blade to the skate. This allowed the skater to push with his feet and then glide along before the next push. The technique was called the “Dutch Roll.” By the end of the 16th Century, skating on the canals of The Netherlands became not only a useful means of transportation between villages, but a pleasurable recreation for the Dutch.

|

|

The Census at Bethlehem . |

Winter Scene with Skaters and a Bird Trap |

We can perhaps credit “The Little Ice Age” with an assist in the development of ice skating and other winter transportation and recreation. This long period of cold weather reigned over Europe form the 14th to the mid-19th centuries. Its cold winters ensured almost continuous snow cover and ice on most bodies of water throughout Northern Europe and North America. An assist for the rise of skating in The Netherlands should also be given to the geographic conditions of the region. Its very flat topography and numerous streams, rivers and canals, which usually froze over each winter, were very conducive to the practice of skating. As a result, all classes of people participated in ice skating in The Netherlands as many paintings by the Dutch Masters (such as the Bruegels above) show. Similarly in Britain, people from all classes participated in skating. Diarists Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn each wrote of skating on the canal in St. James's Park in London during the winter of 1662. (Elsewhere in Europe, it was mostly the upper classes who skated.)

The oldest known document showing a skating scene is a 1498 wood carving published by Johannes Brugmann that showed the disabling fall of a beautiful 16 year old Dutch girl named Lydwine in 1395. According to the legend surrounding the incident, friends had come to visit her in Schiedam and invited her to go skating. She wasn’t feeling particularly well, but they cajoled her into skating with them. Tragically, Lydwine was knocked to the ice and broke six ribs. Confined to her bed for the remainder of her life, she had many visions and was credited with performing miracles. Lydwine was later canonized in 1890 and named the Patron Saint of Skating in 1944.

The oldest known document showing a skating scene is a 1498 wood carving published by Johannes Brugmann that showed the disabling fall of a beautiful 16 year old Dutch girl named Lydwine in 1395. According to the legend surrounding the incident, friends had come to visit her in Schiedam and invited her to go skating. She wasn’t feeling particularly well, but they cajoled her into skating with them. Tragically, Lydwine was knocked to the ice and broke six ribs. Confined to her bed for the remainder of her life, she had many visions and was credited with performing miracles. Lydwine was later canonized in 1890 and named the Patron Saint of Skating in 1944.

The basic skate was refined in the succeeding centuries with metallurgic improvements in the blade itself. Despite the focus on skating by the Dutch, the credit for the invention of the first pair of all-iron skates in 1592 goes to a Scotsman.

Beginning in the 15th Century, the Dutch began organizing speed skating races. Dutch skaters developed the racing technique know as the Dutch pendulum, a technique still used today. The introduction of the iron blade was instrumental in the spread of speed skating competitions across Europe beginning in the 18th Century. Racing in England was contested mostly the working class, many agricultural laborers, on the Fens, a naturally marshy region in eastern England. It is not known exactly when the first skating matches were held, but by the early 19th Century, racing was well established, and results reported in the press. Races were usually “last man standing” events with a pair of competitors racing 660 yards for the right to move on in the brackets. The ultimate winner received half of a purse of £10, a large sum considering the average agricultural laborer earned 11 shillings a week. The British held their first official speed-skating competition on the Fens in 1763, and it covered a distance of 24 km (15 miles).

Organized speed skating races outside The Netherlands and England began in earnest in the 19th century. Norwegian skating clubs held competitions beginning in 1863 in Christiania (now known as Oslo). In 1889, the Dutch organized the first “world” championship with skaters from Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom as well as the host nation participating. The Amsterdam event covering four distances: 500m, 1500m, 5000m and 10,000m. The first official World Championship organized by the International Skating Union was held in 1890 also at Amsterdam.

The only major change in skates since the 16th century, excluding improvements in blade composition, was the wedding of the blade with a boot. This gave more strength to the skating stroke as the skate became an extension of the leg. This innovation is credited to American skater Jackson Haines who directly attached his new two-plate, all metal blades to his boots. Like the stronger, firmer bindings of the Norheim ski binding, the Haines design gave him greater ability to turn quickly. Haines became famous for his dexterity on skates, dazzling the audience with new jumps, spins and dance steps. He later added the first toe pick to his blades, which allowed him to make toe jumps.

The only major change in skates since the 16th century, excluding improvements in blade composition, was the wedding of the blade with a boot. This gave more strength to the skating stroke as the skate became an extension of the leg. This innovation is credited to American skater Jackson Haines who directly attached his new two-plate, all metal blades to his boots. Like the stronger, firmer bindings of the Norheim ski binding, the Haines design gave him greater ability to turn quickly. Haines became famous for his dexterity on skates, dazzling the audience with new jumps, spins and dance steps. He later added the first toe pick to his blades, which allowed him to make toe jumps.

The 19th Century saw a boom in ice skating around Europe and North America, particularly at mid-century. The first skating club in the United States was founded in Philadelphia in December 1849, and people from all walks of life skated in New York’s Central Park, as prints by Currier and Ives show. Speed skating races were also a regular feature of winter life in Canada. Written accounts report Canada's initial long-distance ice skating race took place on the St. Lawrence River in 1854, a race from Montréal to Québec City by three British army officers.

Canada’s first national sports association was the Amateur Skating Association of Canada, established in 1887.

Canada’s first national sports association was the Amateur Skating Association of Canada, established in 1887.

While racing on skates remained a popular competition across Europe and North America, a second competitive form arose in the late 1700s in Britain. (A Treatise on Skating (1772) by Englishman Robert Jones, is the first known documentation of figure skating.) In this form, skaters were judged on their ability to trace compulsory figure patterns into the ice. This discipline gave rise to figure skating or artistic skating which at first differed greatly from the athletic form we now enjoy with its emphasis on the carving of figures (this discipline disappeared from international competitive figure skating in 1990).

The shift to intricate moves began with the development of the new blade and boot assembly by Jackson Haines who set his dance-like movements to music. Though not well received in his native US, Haines took his show to Vienna, Austria. There, it caught the fancy of many, which led to the formation of competitive “figure skating” leagues and championships in what was then known as International Skating. The first European Championship was held in 1891 in Hamburg, Germany in association with the world speed-skating championships.

The first world championship in figure skating under the International Skating Union was held in 1896 in St Petersburg, Russia, and was limited to male competitors. But technically, there was no gender rule at the time, and at the World Championships in 1902, Madge Syers of Great Britain entered the competition and placed second. The discrepancy was rectified and woman’s competitions begun in 1906. Pair skating was added to the championships in 1908. Ice dance did not enter the world championship competition until 1952.

|

|

Winter Landscape With Skaters . |

Dutch Skating Sceneby |

Skating at the Olympics actually predates the Winter Olympics as figure skating (four events) was included in the Summer Olympic Games held in London in 1908. At the first Winter Olympics held in Chamonix, France in 1924, both speed and figure skating competitions were held. Three figure skating events were contested along with five speed skating events, all for men. Women’s speed skating did not become an Olympic discipline until the 1960 Games at Squaw Valley, California, United States. Ice dancing became part of the Olympic figure skating program at the 1976 Games in Innsbruck, Austria. Short-track skating races were added to the Games at Albertville, France in 1992. The Vancouver Winter Olympics will contest 24 skating events (4 figure skating, 20 speed skating, and 8 short-track skating)

The final winter sport/recreation I want to mention is sledding, also known as sliding. Like skiing and skating, sledding has it origins far back in prehistory and may have coevolved with skiing as a form of transportation over the snow and ice. (Which came first may be the old “chicken or egg” dilemma.) Sledding remained an important form of transportation into the 20th Century as it was easier to transport heavy loads by sled over a frozen surface than a non-paved road.

The earliest sleds were pulled by humans across the frozen surface. Along the way, however, we learned to domesticate animals such as dogs, reindeer, horses, and oxen to pull sleds for us. Sled forms ranged from simple platforms with or without runners to elaborate sleighs for the rich and aristocracy.

|

|

|

Detail of basic sled |

Winter Scene |

Horse-draw sledge in Russia |

Technically, there are specific terms for the various devices used to slide across or down snow/ice: sled, sleigh, sledge, or toboggan. A sled generally refers to a small device that moves by sliding on a pair of runners, often pulled by a human or perhaps by small animals, or propelled by gravity. A sleigh is typically a partially enclosed vehicle with seats for passengers that is usually drawn by animals and slides on runners. (The bobsled or bobsleigh is technically a sleigh as it is a partially enclosed vehicle with seats.) A sledge is usually a rough, sturdy, load-carrying vehicle pulled by draft animals or dogs, or motorized engine. A toboggan is a traditional form of sled developed by the Innu and Cree of northern Canada and now used for recreation to carry one or more people down a hill. Unlike recreational sleds that have runners, the toboggan rides directly on top of the snow. The traditional toboggan is made of bound, parallel wood slats, which bent at the front to form a 'J' shape, although today, a toboggan may be made of wood, metal or plastic.

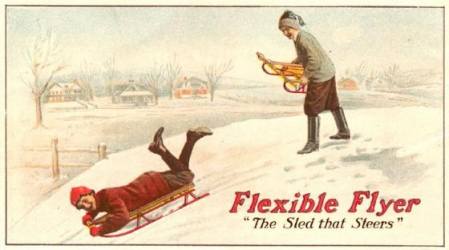

The most recognized form of sled today is the “flyer” sled, the iconic toy of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, featured in films such Citizen Kane (“Rosebud”). The first Flexible Flyer Sled was the brainchild of Samuel Leeds Allen, a Pennsylvania Quaker farm implements manufacturer named. The Flexible Flyer, patented February 14, 1889, features a pair of steel runners with a bendable spot halfway down the sled that gives some degree of steerage. Runner sleds are not as efficient on soft snow as the toboggan, but are faster when the snow has become compacted or turned icy.

A number of other sliding devices have evolved over the years, particularly with the introduction of materials such as light, smooth metals, plastics and even synthetic cloth that can glide across a snowy/icy surface. Some are actually designed for sliding down slopes such as the “saucer” and “magic carpet” forms, and some are improvised sliding devices such as the cafeteria tray (traying was a popular winter diversion during my college days), large sheets of cardboard, inflated inner tubes (tubing), and even one-piece snowsuits. On the latter, I remember my son, wearing a nylon-type snowsuit, slipping as we climbed the local toboggan hill and sliding on his back down to the outrun — so much for the toboggan.

Sledding lore suggests that recreational sledding began when a few Brits decided to have some fun with a delivery sled in 1870 in St Moritz, Switzerland. Perhaps that is true for adults. But in January 1775, a group of young (thirteen or fourteen years old) Bostonian students petitioned the British General Fredrick Haldiman to allow sledding (they called it “coasting”) down Beacon Hill onto School Street. In a note written by John Elliott to the Rev. Jeremy Belknap, he reported:

“You may remember there is a declivity from the lane opposite School Street, which is the winter season the boys make use of as a coasting-place. Here not long since a number of boys were assembled for the purpose aforesaid. A servant of General Haldiman’s (whose stables were in that lane), being displeas’d by the slippery walking their amusement occasioned, maugre their pleadings & threatnings, scattered ashes over the place, & spoiled their fun. … a committee from the boys, sent to make complaint of the invasion of their rights made by one of his servants; that he had spoiled their sport by tossing a quantity of ashes over a spot of ground which they & their fathers before them had taken possession of for a coasting-place.”

The boys receive a positive response to their petition from the General.

It likely did not take long in the evolution of sleds for someone to ride one down a hill and feel the thrill and thus was born sledding as a recreation. And I would imagine, not long after that someone yelled “race you down the hill” and competitive sledding was born. For sleds pulled by animals, particularly dogs and reindeer, the desire to see whose team was fastest also has its beginnings lost in antiquity.

The major proponents of animal/sled racing are the cultures native to the Arctic regions in North America, Scandinavia, and Russia. An annual Reindeer Racing World Cup is held annually in Kautokeino, Finnmark, Norway as part of the Sami Easter Festival. (Actually, in this competition, the reindeer pull the competitors on skis rather than in sleds.) Two races are held: a sprint races of 201 meters (660 feet), and a distance race of one kilometre (5/8 mile).

|

|

Reindeer racing at the-Sami Easter |

Norwegian Musher Robert Sørlie in the |

Sled dog races are held across the arctic region, particularly in Canada and Alaska. The world’s premier event is the annual Alaskan Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. The Iditarod pits teams of 16 dogs (plus musher) racing over the distance of 1161 miles (1868 km) from Willow Alaska (near Anchorage) to Nome. Depending on snow and weather conditions, the Iditarod takes between eight to fifteen days to complete. Another major sled dog race is The Yukon Quest 1000-mile (1600 km) International Sled Dog Race run every February between Fairbanks, Alaska, USA and Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada. The longest sled dog race in Europe, and the northernmost race, is the Finnmarksløpet, a 1000-km (623 mile) competition starting in Alta, Norway.

Sled dog racing was a demonstration sport at the 1932 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York. And while both reindeer and sled dog racing have a long tradition and history and continue to be popular, I will leave these particular winter activities/sports to focus on the sliding races that have become part of the Olympic Games.

|

|

A bobsleigh team in Davos, ca. 1910. |

An East German bobsleigh in 1951. |

The roots of the modern sledding sports — the lug, the skeleton, and the bobsled — began in the 1870s in St Moritz when English tourists to this picturesque village joined with local Swiss craftsmen to build the first recreational sleds. They had enjoyed sliding downhill on delivery sleds/toboggans but wanted the ability to steer their way down the narrow streets of the village. The result was the first bobsled. To accommodate this new activity, the owner of the Klum Hotel, Caspar Badrutt, had the first course built for the nascent sport. (The course was as much for the safety of the local pedestrians as for the sledding enthusiasts.)

The three sleds were designed in the Alps and used in competition, which differ in design and method of riding.

The bobsled, or bobsleigh, originally was comprised of two runnered sleds strapped together with the ability to steer added, but the design later became a single steerable sled with added sides and front cowling for aerodynamics. The bobsled is the only competitive sled where the participants sit on the sled, and for which there is no single rider competition. Two or four rider events are contested today. |

|

A luge is a small one- or two-person runnered sled on which riders lie on their backs, sliding down feet-first. There is no braking mechanism, save the rider’s feet. Steering is accomplished by flexing the sled’s runners with the rider’s calves and by exerting shoulder pressure to the seatbed. At one time, luges had a sliding seat, added in 1902 by Arden Bott, to help the riders shift their weight forward and backward for steering; however, that feature is no longer part of modern sleds. |

|

The skeleton originally closely resembles a toboggan. But in 1892, L. P. Child introduced the “America,” a new metal sled that revolutionized skeleton as a sport. The rather flat, stripped-down design provided a compact sled with metal runners underneath the sled. Racers ride the skeleton downhill on their stomach, face-first, with their arms to their sides. The skeleton sled has no steering or braking mechanism; therefore, the riders use movements of their body to alter the sliding path. In current competition, skeleton riders use the same tracks as the bobsled and luge. |

|

While Europeans took to racing the lug, the skeleton, and the bobsled, Americans enjoyed tobogganing in the second half of the 19th Century and into the early decades of the 20th when tobogganing. The Montreal Tobogganing Club was formed in 1881 using the Mount Royal slopes in Montreal for their runs. But one of the more popular runs for recreational tobogganing in Canada was, and still is, located in Quebec City. The Dufferin Terrace Slides (Glissades), located on the Dufferin Terrace in front of the Chateau Frontenac, boasts steep 285-foot-high wooden toboggan tracks. The popularity of sledding declined with the rise of alpine skiing in North America and Europe, but it remains a major recreation for the young and young at heart in any area with sufficient snow cover.

Sledding has been a part of every Winter Olympics since Chamonix in 1924 with the exception of the Squaw Valley, California Winter Olympic Games in 1960 where no sliding track was built. Bobsledding, or bobsleigh, has been contested at each Winter Olympic Games, save the 1960 Games. The initial event was a four-man event (five riders in 1928), and a two-man event was added in 1932. A two-woman race joined the Olympics in 2002 in Salt Lake City. Luge races for men, women and men’s doubles made their Olympic debut at the 1964 Games in Innsbruck, temporarily replacing the skeleton. Skeleton racing for men was contested in the Winter Olympic Games when the Games were held in St Moritz in 1928 and 1948, but was then removed from the program until the 2002 Olympic Winter Games in Salt Lake City. Skeleton for both men and women has been part of the Games since then. The Vancouver Winter Olympic Games will host eight sledding events: three in bobsleigh, three in luge, and two in skeleton.

Skiing, skating and sledding are just a few of the sports and recreations one can enjoy over the winter months, and they are not exclusive to Olympic-class athletes. All were recreations — a fun thing to do — before they became competitive sports. My favorite winter sport has been cross country skiing which I began my first winter in Canada. After a hiatus when I lived in Victoria, BC, I have again begun to ski here in Valemount, and recently introduced my oldest grandson to cross country skis.

One great sidebar to winter recreations is that it gets you out of doors and opens the opportunity to see some beautiful snow-covered landscapes and skyscapes. Be on the watch for diamond dust, haloes and light pillars, which are common in the winter, and if you go out at night, there is the possibility for seeing an auroral display as well.

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

Now |

The BC Weather Book: |