|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

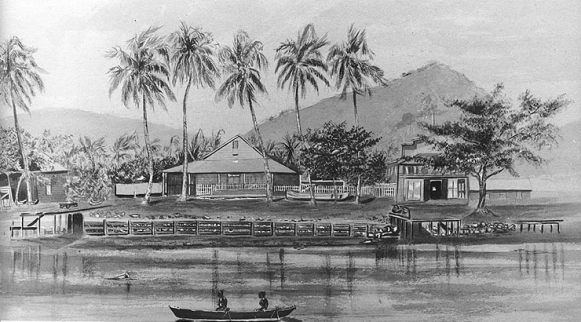

Weather Almanac for March 2009THE SAMOAN HURRICANE OF 1889Storms and weather have played pivotal roles in world history, and often during times of war, they have altered the balance in the fighting. Such interactions at sea have had major influences on the course of engagements such as the devastation caused by the "divine wind" on the Chinese fleet sent to invade Japan in 1281; the battering of the Spanish Armada in 1588 by severe storms of the European coast; and the hammering of the US fleet in 1944 by a typhoon of the coast of the Philippines. But in 1889, a tropical cyclone — a hurricane in American terms, a typhoon in west Pacific nomenclature — may have averted armed conflict between the United States and Germany in the remote South Pacific. The Scene Apia facing the Entrance of Harbor prior to the storm." |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

German corvette Olga |

German gunboat Alder |

German gunboat Eber |

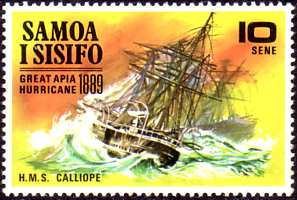

American commercial interests felt threatened, and they asked for military support which arrived in the form of three warships commanded by Rear Admiral Lewis A. Kimberly: the flagship USS Trenton, and two smaller naval vessels Vandalia and Nipsic. These six warships were joined in Apia's small, and unprotected, harbor by the British corvette HMS Calliope. About ten non-military vessels also lay at anchor in the harbor.

|

|

|

USS Trenton |

USS Vandalia |

USS Nipsic |

Tensions among the military vessels ran high, and there was concern that the Americans and Germans would turn saber-rattling into cannon fire at any moment. Then the weather intervened.

The peak of hurricane (typhoon) season in the Samoan Islands region is from the end of January to mid-March. And while tropical storms don't strike Samoa (Samoa and American Samoa) often, one had struck the islands and Apia three years previous. In fact, locals had been on edge as a number of fierce storms had struck Apia earlier in the year. Indeed, days before the hurricane in question struck, a fierce gale had lashed Apia. While these storms had swamped or blown ashore a number of smaller ships, they had done little damage to the larger warships that lay at anchor in the harbor. Only the Eber had been noticeably damaged when one of its screws had struck the reef.

As the latest gale subsided, the massive USS Trenton entered the harbor on calm seas and light winds on Thursday 14 March. But the experienced sailors, both officers and crew, sensed all was not well as the barometer continued to fall steadily all day. Captains from all the ships went ashore to confer with the old seamen of the island who might best interpret the weather signs before them. The opinion was nearly unanimous among the old salts. The signs spoke of coming heavy rains but the winds would not be a worry. Hurricane season was over.

Navigating Officer Lieutenant Henry Pearson of HMS Calliope, however, held an opposing opinion. He viewed the falling barometer and the rising offshore and southerly wind and concluded it had but one interpretation: hurricane. He advised Captain Henry Coey Kane to move Calliope out of the crowded bay and away from the reef. Kane over-ruled his officer based on the advice he was given ashore and the fact that Callope had weathered two previous gales with no problems. If the American and German captains has second thoughts about staying, they were ignoring any contrary advice. This was a nose-to-nose military confrontation with fighting seemingly just hours away, and neither would relinquish the harbor to the other.

|

|

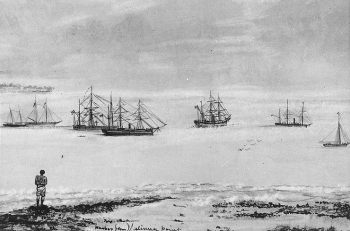

US, German and British warships, |

Harbor from Mulinuu Point |

At dawning Friday 15 March, the winds had indeed dropped and the still bay shone with a greasy oil slick. The air hung hot and humid, even for a tropical clime. Aboard the warships, their navigating officers noted the barometer continuing to drop. Soon the orders were given to prepare for a heavy blow: "strike the lower yards and top masts." This meant not only to lash the sails to the lower yards but also to remove the yards from the masts and stow them on the deck. So too, the upper portions of the foremast and main mast were detached and lowered to the decks for lashing against the lower sections of the mast. This left the ships with only their gallant yards available for sail. Added anchors were set to hold position if wind and wave pushed the ships from their station. All began to build steam in their boilers in case ship engines were needed to keep a vessel from dragging its anchor.

In mid-afternoon, the skies darkened and the rains came. Not gentle, or even heavy, rains but torrential rains that formed massive sheets of water striking hard like bullets under the push of an ever-strengthening wind. Its heavy curtain veiled the bay, cutting visibility so that lookouts could not see the other ships around them, let alone the shore and reefs. On the waters, waves began to build. Fortunately, this initial blow came from the south — overland, which was of less danger to ships in the harbor.

Initially, the forecasts of the old salts on land held. They had foreseen a period of heavy rain but added that after it began, the winds would subside. Indeed, following the rains, the barometer rose and the winds died as predicted, indicating the storm had moved out to sea. However, in the following hours, all involved were shocked to see the barometer again rapidly fall and the winds rise rapidly, this time from the north.

With the sudden shift of the rising winds to the north, wind and surge now entered Apia harbor from its open end. Apia harbor was not a place to ride out a hurricane. It was a V-shaped basin formed by the outflow of freshwater from the Vaisingano River through the coral reef. It was an exposed harbor, its northern waters open the the Pacific and having no high ground or enclosing reef on its island edges. Coral banks formed the edges of the basin. If the wind and surf pushed in from the north, any ship unable to withstand the onslaught would be driven onto the coral reefs or tossed onto the beach.

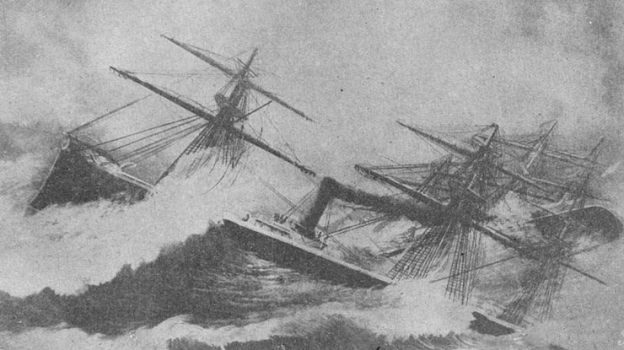

All evening the winds continued to rise, reaching gale force by midnight. Soon, Captain Kane would call it a hurricane as the winds blew into the harbor at estimated speeds of 70 to 100 knots during the night. All ships were straining against their anchor lines and steaming hard to ease the strain. Within the crowded harbor, the pitch-black night and heavy seas robbed officers and crew of the ability to see any of the other vessels even if only a few metres (yards) away.

Through the night, no one slept as ship's tried valiantly to keep their position away from the reef and other nearby vessels. Two merchant ships, the Danish ship Santiago and the German barque Peter Godeffroy collided and sank. Even at full steam, the warships were unable to keep their anchors from slipping, and they moved closer to the reefs … and each other. Eber's screw, damaged by the earlier storm, failed thus leaving her to the mercy of the wind and wave. Just before dawn, the drifting Eber capsized and was pounded to pieces by the surf. All but five of her eighty-seven crewmen perished.

Aboard Adler, Fregattenkapitan Fritze saw a similar fate awaiting them after collisions with Olga and Nipsic had severely damaged Adler's hull. He ordered the hawser line slipped just as huge wave approached, hoping it would toss his ship onto the reef rather than against it. The waves did flip the thousand tonne Adler onto the reef but she was pushed on her side. Fifteen of its 128-member crew were lost, many of the survivors clung to the rigging for hours as the storm pounded the marooned ship.

Rather than risk the perils of the reef, Commander Dennis W. Mullan ordered the damaged Nipsic grounded on a small stretch of beach along the eastern shore where the reef was absent. He succeeded, but not before colliding with the Lily a small schooner, which sank rapidly, moored in his path. Mullan lost seven of his 180 officers and crew to the storm.

On shore, all were hunkered down before the blow, and many locals tried to reach the harbor in the vain hope of helping those aboard ships. The thrashing waters of the Vaisingano washed away all bridges crossing it.

As the storm winds rose, the USS Vandalia and the USS Trenton had taken station at the outer edge of the harbor with all the other vessels between them and the reefs. Vandalia was having trouble countering the fury of the storm and surf, her anchors slipped along the bottom, and some cables had broken. The seas and wind drove her toward the inner-lying ships Olga and Calliope. As she passed, the ship collided with Calliope, severing one that ship's three anchor cables. Vandalia also bounced of Olga several times during the chaos. The seas pushed Vandalia closer to the southern portions of the reef and for a brief time, looked as if she would be grounded on the sandy beach. Despite a heroic struggle with the elements, Vandalia eventually lost its battle in the early afternoon of the 16th when her stern caught the reef at the southern reach of the harbor and foundered. A large wave swept across the deck and knocked Captain Cornelius M. Schoonmaker against a deck gun. A following wave carried the unconscious captain and several crewmen to their deaths in the roiling seas.

Those on land watched helplessly as the Vandalia crew tried to get a line ashore across a distance of less than 100 yards. Every boat launched from Vandalia was quickly swamped by the ragging seas and pulled to the middle of the harbor where its crew drowned. One brave Samoan Teoteo "made a desperate attempt to swim off to the Vandalia with a line while the gale was at its height. The heavy surf, the jagged reef strewn with wreckage and swept by strong currents, through and over which he attempted to pass, made this effort one of exceeding danger, and in the futile attempt he nearly lost his life." With few options left, the remaining crew scrambled into the rigging and hung on. Miraculously, the crewmen in the rigging were able to transfer to the Trenton, the account of which is given below. Of Vandalia's 200 crewmen and officers, 43 drowned, including three officers and Schoonmaker.

At dawn Saturday (16 March), Captain Kane called the situation "as bad a one as you would care to enter." Vandalia was careening into the bay, striking Calliope and Olga on its way to destruction on the southern reef. By afternoon, only USS Trenton, HMS Calliope and SMS Olga, the largest of the warships in the harbor, continued their fight against the hurricane and its enraged seas.

SMS Olga, under the leadership of Corvette Captain Baron Freiherr von Erhardt, had begun the fight against the storm as the innermost ship in the anchorage and about centered between the reefs to the left and right. As the storm raged and tossed ships around the bay like toys, Olga suffered collisions with Adler, Vandalia, Calliope, and Trenton. Despite heroic maneuvering by her helmsman, Olga sustained violent collisions with Trenton that severed two of Olga's anchors. Erhardt realized that with only two remaining anchors, he could not hold the ship off the reefs, and took the chance that he could safely ground the 2400-ton vessel. Dropping his remaining cables, he pushed his engines to steam crosswind to the eastern sand beach. Eventually, Olga was thrown high onto the beach on the eastern shore; all of her 267 crew survived the ordeal.

When the storm began, the USS Trenton was anchored the furthest out of the seven warships, just ahead of Vandalia. She was captained by Norman Von H. Farquhar, who remained on the bridge through the entire ordeal. The vessel held its own against the storm until the early afternoon "when the flagship lost her wheel ... carried away with a crash and seriously injuring some of the helmsmen ...." Despite attempts to repair the tiller and wheel, Kimberly realized that "it was discovered that the rudder was broken, and soon it was entirely useless."

"The wind by this time was blowing with hurricane force and the seas were very heavy," Kimberly reported. "The ship was beginning to make water during the early morning. The hand pumps were manned and all bilge pumps in the engine room put on....It could be checked in this way but not stopped, for the violence of the seas was so great that it would force back everything that opposed it....but by 9:30 am, the fires had been put out and the men driven up from the fireroom."

|

|

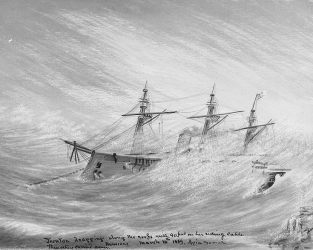

Trenton dragging along the reefs. |

Trenton dragging along the reefs |

In the heavy seas rolling in from the ocean, her low hause pipes had allowed water to enter ( a well-known defect in her design), dousing the steam powerplant. Without steam to power her screws and no rudder, Trenton was at the mercy of the pounding storm. With her rudder smashed, Trenton's dragging anchors provided little hope of keeping the ship out of danger. Eventually, the dragging anchor cables parted, and Trenton was at the mercy of the seas.

On her wild ride, Trenton collided with Olga and nearly with Calliope. Her officers trying to manage her by the storm sails. Trenton nearly hit the eastern reef but then was blown toward the western reef. Kimberly reported: "About 6 o'clock we were expecting to strike the reef momentarily. It was directly under our stern, but, as on the eastern side, an under tow or current seemed to carry us along the reef and keep us just clear of striking. Thus, we came down to where the Vandalia was lying, and it was evident that our stern would soon strike against her port side."

As she approached Vandalia, miraculously the storm subsided briefly. With the two vessels so close, Trenton launched rockets carrying lines toward Vandalia's masts. Many of Vandalia's crew were able to scramble from their ship's rigging to the Trenton. Just as the last man clinging to Vandalia's rigging left, the storm rose again and smashed the two vessels together. The force of the collision tossed Vandalia's mast into the raging sea.

Trenton was now beached by the storm. But her hold on the beach was tenuous, unlike Olga's firm beaching, and the waves drew her back into the bay, eventually dashing her on the reef at 10 pm. Though wrecked on the reef just north of Vandalia, none of her crew of 420 men were lost according the official report from Admiral Kimberly but one landsman aboard died when the seas stove in a porthole. All of those members of the Vandalia crew who had made it aboard Trenton also survived.

Unless noted otherwise, all photographs and drawings courtesy of the US Naval Historical Center. Paintings of the event by Rear Admiral Kimberly were done during his retirement.

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

Now |

The BC Weather Book: |