|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

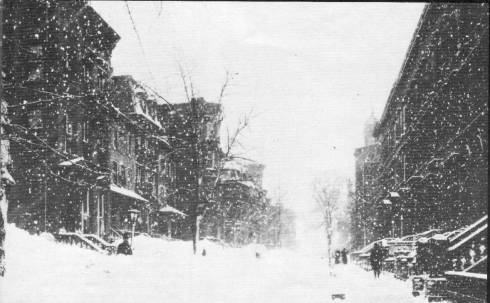

Weather Almanac for March 2008THE GREAT BLIZZARD OF ‘88Growing up as a fledgling weather fan and future meteorologist, I frequently ran across references to the Blizzard of ‘88. Until a few years ago, the name meant to me the great blizzard that dumped several feet of snow on New York and other areas of New England. But in 2004, I was asked to review the book The Children's Blizzard by David Laskin which dealt with a blizzard in 1888. I soon realized that this blizzard, which struck in the American Plains states, was not the same storm which struck the East Coast, nor was it associated with that storm in its early life. No, the two blizzards were separated by two months: the Children's Blizzard, striking in January and the East Coast blizzard of ‘88 raging in March. When I decided to write about the New England storm on its 120th anniversary, I realized that I should tell the story of the earlier blizzard as well. Then in researching those stories, I found that there was more than just the tale of two blizzards. In the wake of the January blizzard, temperatures dropped across the American plains to levels unprecedented in the meteorological record prior to that date. The great cold wave of 1888 placed another story into the history. In this Almanac, I write about the Great Blizzard, but I have added articles in the Events section of this site on the infamous Children's Blizzard of January 1888 and the deep cold wave that followed in its wake.  Looking toward New York City Hall Building, 13 March 1888 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|  |

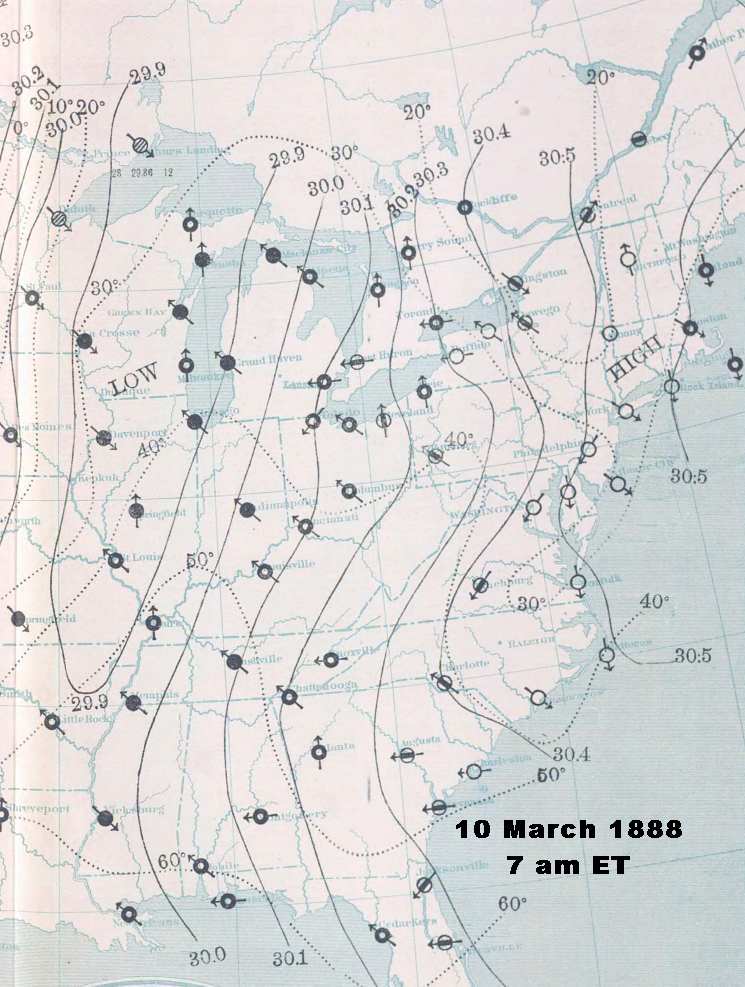

Weather Map: 10 March 1888: 7 am ET | Weather Map: 11 March 1888: 7 am ET |

Weather maps courtesy: NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project | |

The cold air was rapidly advancing from the Upper Mississippi Valley and western Great Lakes toward the coast and into the south, and a cold front developed behind the southern low. While at midday (3 pm), Augusta, Georgia was a mild 64 oF (17.8 oC), behind the front, Chattanooga, Tennessee had dropped to 38 oF (3.3 oC). To the north, the temperatures in Ontario and upstate New York had fallen to the 20s F (minus single digits C) while in northern Michigan they had sunk to the teens or lower (minus teens C).

The rain that had been falling behind the cold front from Virginia to Maryland, including the nation's capitol, changed to snow during the afternoon. Heavy snow began in Washington at 5 pm and at Baltimore, Maryland at 7 pm.

By 10 pm, that southern low had moved off the Virginia coast, and had quickly deepened. Wind speeds along the Virginia, Maryland and Carolina coasts rose rapidly. They blew roofs off houses and uprooted trees, but the most damage came to ships in supposedly protected areas. Nearly 100 sea-going vessels received damage, were sunk, or were driven ashore as the storm winds struck the coast. Norfolk, Virginia and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina both reported average wind speed of 48 mph (77 km/h) at 10 pm. Washington had, by now, received 3 inches (7.6 cm) of snow, drifted by northwest winds blowing at 25 mph (40 km/h). Baltimore had 6 inches (15.2 cm) on the ground.

News reports from Baltimore indicated "a heavy storm has prevailed all day in that locality, and it is evident that its fury has to-night assumed the proportions of a hurricane in the immediate neighborhood of Washington." The heavy snow and wind cut communications with the city. The only telegraph line in Washington remaining in service ran underground from the Capitol to the White House. The high winds on the Potomac River caused an unusual situation. Water levels on the river dropped to unprecedented levels leaving the ferries linking the Capitol with Virginia high and dry, stuck in the mud. In some locations, the exposed river bottom froze solid, hard enough to walk on.

The cold air was reaching the northern coastal areas as well. Philadelphia reported heavy rain, amounting to 1.16 inches (29.5 mm) over the past seven hours, before it change to snow with the frontal passage just before midnight. In New York City, rain-slicked surfaces began to ice as the temperature dropped to freezing as Sunday ended. The worst was yet to come.

Overnight, the storm continued to intensify over the Atlantic waters, its center now located southeast of Long Island, New York. From that position, the winds blowing around the low pressure cell hit New England with northeast winds, making the storm a classic Nor'easter, that initially brought heavy rain to the area. Behind the storm center, very cold air rushed in from an arctic high pressure cell located across the Great Lakes. The dome of arctic air expanded over western New York as the day progressed, pushing the cold front across Pennsylvania, New York, and New England. When the front passed and temperatures fell below freezing, rain changed to snow. The change came shortly before midnight in Philadelphia and around midnight in New York City. The snows started in New Haven, Connecticut at about 2:30 am. The cold front then stalled along the coast where it would remain for the next 48 hours.

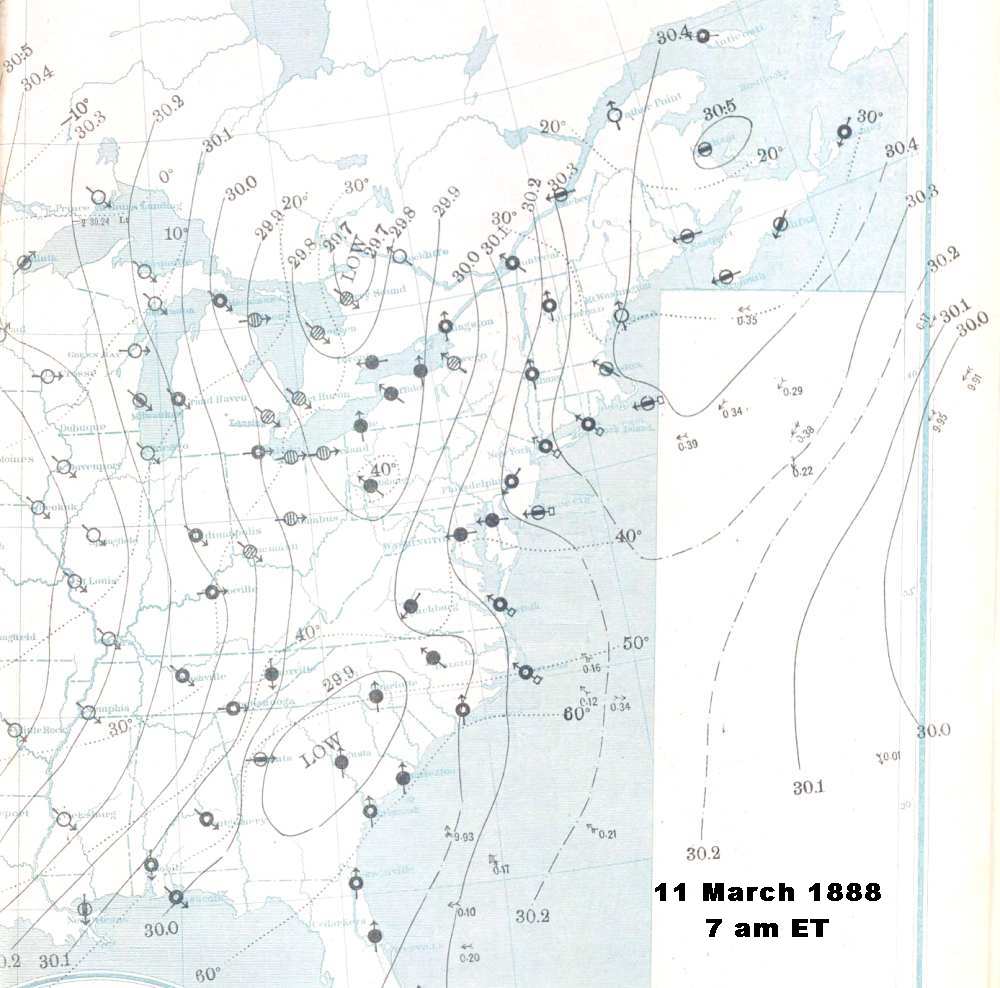

The storm's central pressure at 7 am, 12 March, was measured by a ship at sea at 29.43 inches Hg (996 mb). With the high pressure cell over northwestern New York at around 30.3 inches Hg (1026 mb), the tight pressure gradient drove the cold air into the New York–New England region on gale-force winds. Thus, the morning weather along the coast ranged from very cold and windy in Virginia and Maryland, where the snow had ceased overnight, to near-blizzard conditions across eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and interior New England. Philadelphia and New York City both reported 10 inches (25 cm) of snow on the ground ,flung around by winds averaging 30-50 mph (50-80 km/h). Winds along the coast gusted to near-hurricane force at Block Island, Rhode Island: 70 mph (112 km/h); and to hurricane force at Atlantic City, New Jersey: 80 mph (128 km/h).

During the day, the storm center drifted slowly past Long Island to south of Rhode Island. As the day wore on, it continued to deepen, measurements at Block Island and a nearby ship placed its pressure at around 29.3 inches Hg (992 mb). The region of maximum precipitation now settled over eastern New York State and lower New England, mostly falling as snow. To the rear of the storm, the snow had ceased in Philadelphia and southern New Jersey, but with cold air and howling winds, true blizzard condition now prevailed. New York City and environs lay under 16-24 inches (41-61 cm) of snow. Winds remained strong (30-50 mph / 50-80 km/h) and the temperatures had dropped to bitterly cold levels: the teens Fahrenheit — generating windchills by today's formula as low as -15 oF (-26.1 oC). In areas of New England divided by the frontal divide, temperatures differed by 10-20 F deg (5.5-11 C deg) across the front during the afternoon. As it moved closer to the coast, rain changed to sleet, then to snow . . . heavy snow.

By 10 pm (12 March), the storm was centered between Block Island and the southeast Massachusetts coast with central pressure approximately 28.9 inches Hg (978 mb). The frontal divide between the two air masses had nearly reached the coastline, and the contrast was even greater than during the afternoon. Albany, New York and Northfield, Vermont both recorded -4 oF (-20 oC) while in the warm sector, the temperature at Nashua, New Hampshire registered 34 oF (1.1 oC) and Boston 32 oF (0 oC). At midnight, the temperature in New York City was 8 oF (-13 oC) and falling under strong westerly winds. The snow continued in the City with 21 inches (53.3 cm) accumulated in Central Park by midnight. Upstate, Albany had received 31 inches (78.7 cm) of snow and nearby New Haven, Connecticut, 28 inches (71.1 cm) — daily accumulation records which still stand.

|  |

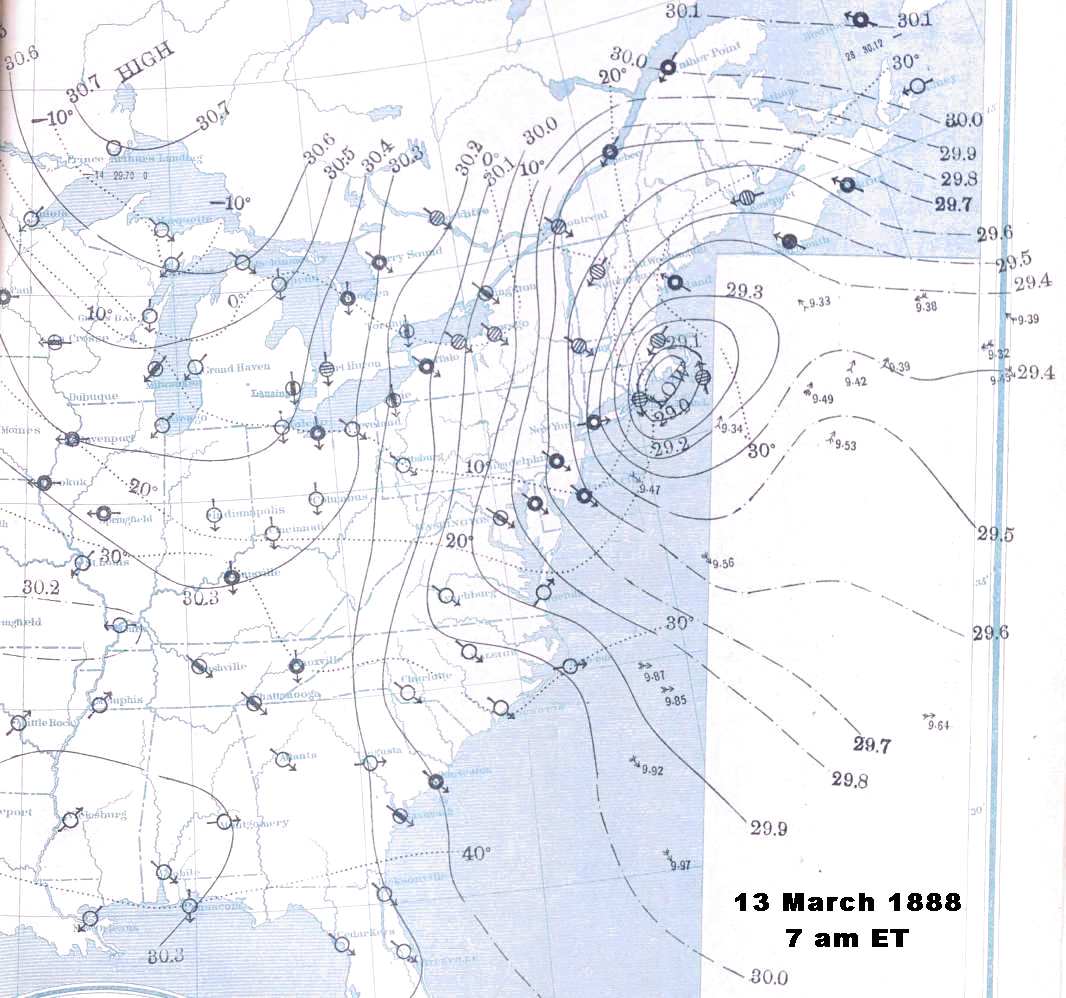

Weather Map: 12 March 1888: 7 am ET | Weather Map: 13 March 1888: 7 am ET |

Weather maps courtesy: NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project | |

As the storm system began to occlude, the cold air wrapped around it, and parts of New England saw snow falling under southerly winds. Through the night of the 13th, temperatures along the coast continued to fall. New York City would bottom out at 5 oF (-15 oC), but the temperature would not change much all day and the mean temperature in Central Park for 13 March would be 8.5 oF (-15 oC). The position and central pressure of the storm changed little overnight; in fact, the storm would remain quasi-stationary from 3 pm on the 12th to 7 am on the 14th.

Snow continued to fall over New England and most of New York throughout the day, and although little snow fell over New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania, the strong winds, blowing snow and cold temperatures produced blizzard condition there. Paterson, New Jersey dropped to -4 oF (-20 oC) and much of New York State and Pennsylvania shivered in near 0 oF (-18 oC) temperatures. During the 13th, the winds remained strong across much of the region as the snow continued to fall, though not as heavy as earlier, accumulating around 10 additional inches through much of the affected region.

By the morning of the 14th, the storm was diminishing rapidly and moving out into the Atlantic Ocean. Snow tapered off or ceased altogether, only a few more inches added to the snowfall in some areas. Temperatures rose to freezing and above over much of the area by midafternoon.

The Great Blizzard of 1888, it appears, was not yet done. Though it had significantly weakened — ship reports place the central pressure at around 29.6 inches Hg (1002 mb) — by the morning of the 14th, it may have regained strength on crossing the Atlantic over the next two days, because Great Britain, particularly Scotland, was hit on the 16th by a strong gale and heavy snowstorm that downed telegraph lines.

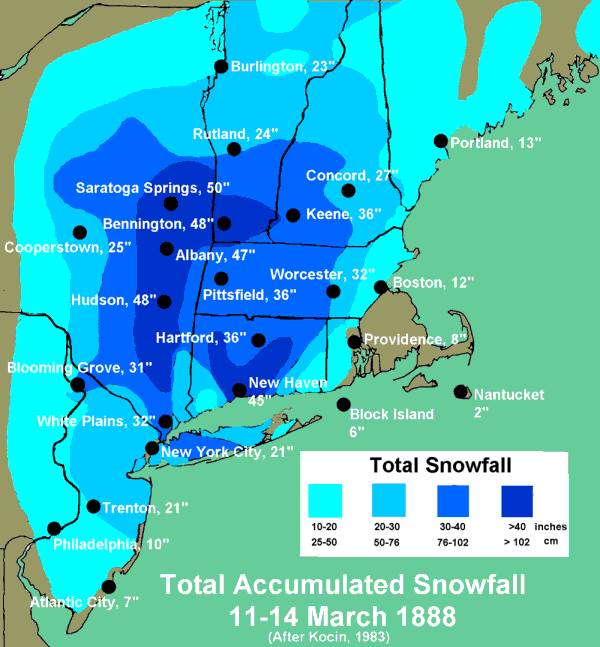

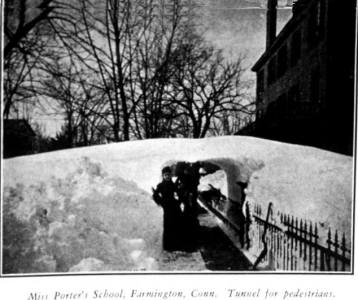

The aftermath: Across the northern US Atlantic Coast, except for northern Maine, Rhode Island, and eastern Massachusetts, snowfall totals exceeded 10 inches (25.4 cm) during the period 11-14 March. The accumulations ranged from 7 inches (17.8 cm) in Atlantic City and 10.5 inches (26.7 cm) at Philadephia to 50 inches (127 cm) at Saratoga Springs, New York. Troy, New York received the most snow, a whopping 55 inches (139.7 cm). Hudson and Albany, New York both totalled over 40 inches (101.6 cm) as did New Haven, Connecticut and Bennington, Vermont. (Given that the wind blew snow around continually during the storm, some of the accumulations may have been measured higher or lower than the actual fall amount.) The depth of the drifts formed by the heavy snowfall and powerful winds almost staggers the imagination: 10-20 feet (3.1-6.2 m) in New York's city canyon; 15-40 feet (4.6-12.2 m) in Bangall, New York, and a 38 ft (11.6 m) drift in Cheshire, Connecticut. A drift outside Bridgeport, Connecticut measured 10 feet (3.1 m) high and stretched almost a mile (1.6 km) in length!

The Blizzard of ‘88 hit the United States in its jaw, crippling of the Northeast from southern New Jersey to southern Maine. It affected a high proportion of the nation's population — about one-quarter — directly. Under its rage lay four of America's six largest cities; 23 of the top fifty. The storm cut off communications with the nation's capitol Washington DC, Philadelphia, New York City and Boston, and then cut off transportation to the latter cities. Hundreds of smaller cities and towns were buried under snow. In the worst hit areas, residents remained confined to their homes for as long as a week.

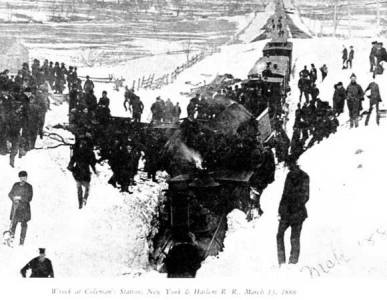

By mid-morning on the 12th, all northbound trains stopped running beyond Philadelphia. Pennsylvania Railroad's Congressional Express required nine hours to make the run from Washington to Philadelphia, normally a three-hour jaunt, and did not continue to New York City for two days.

Many trains were caught on the tracks between towns, and passengers were forced to wait out the tempest in poorly heated passenger cars with little food available. The Albany Express became snowbound at Hastings-on-Hudson for 48 hours. Many of the passengers were so moved by the experience that they formed a small association The Snow Birds and resolved to meet annually on 12 March to remember the event. Two trains, one from Chicago and one from upstate New York, collided at Dobbs Ferry, twenty miles north of New York City, injuring dozens of passengers and crewmen. In New York City, rail transport ceased for days.

Huge drifts at Westport, Connecticut across the New York–New Haven rail line were not cleared for eight days following the storm. The Danbury (CT) Evening News reported one locomotive attempted to force its way through a large drift. "The cowcatcher strikes the drift, sending showers of pieces 50 feet[15.2 m] in the air." Like a moth caught in a spider's web, the locomotive tried to extricate itself from the drift to no avail, making ."one or two spasmodic efforts to go forward, but the drivers slipping on the rail refuse to budge an inch.... Then the lever is reversed, but still the monster cannot be stirred."

On 14 March near Three Bridges, New Jersey, four locomotives were coupled together to tackle the drifts over the Lehigh Valley Railroad tracks. When a drift proved too strong for the quartet, they were brought to a sudden halt, and the locomotives were thrown from the track. Engineer Dory Apgar and Conductor Andrew Bullman on the first engine died in the wreck. Conrad Derr, the engineer on the second also died, and his fireman Isaac Pixley was badly scalded and lost a leg in the mishap. Drifts proved the master over locomotives in New York City as well. Three locomotives attempted to push through drifts outside Grand Central Station but were repulsed, one thrown from the rails in the attempt.

The storm hit an area rich in maritime commerce and caught many vessels along the coast — in port or out at sea — in its fierce winds. An estimated 200 vessels were sunk, wrecked or grounded. Mariners called the storm "the White Hurricane." In Philadelphia harbor, 27 of 40 ships were disabled or destroyed. Overall at least 100 seamen died, a third of them in Philadelphia waters.

The American vessel Annie M. Small approaching New York from a voyage from Columbo Ceylon (Sri Lanka) encountered the storm on 12 March off the New Jersey coast and reported the winds blew at Force 11 to 12 on the Beaufort Scale, storm to hurricane intensity. She first lost the lower foretop sail and the main topsail, and then lost both topsails. The gale blew the ship on beam-ends so that its yard-arms dipped into the water. One crewman was washed overboard but rescued; five men suffered frostbite on feet and hands. More damage followed as the day progressed. The captain wrote in his logbook: "This is the worst gale I ever experienced; ship making bad work of it and straining badly."

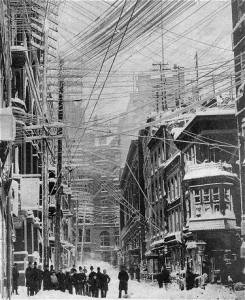

Prior to the storm's hit on the northern coastal areas, it cut communications lines to all areas south of Baltimore, Maryland, including Washington DC. In the cities and large towns throughout the Northeast, the storm took out untold numbers of telephone, telegraph, and electric light wires. Snapping them and their supporting poles under the combined stress of wind, snow and ice. Western Union estimated their losses at over $100,000 ($2.2 million in 2007 dollars). The rampaging storm demolished New York City's telegraph system, and was a major contributor to the practice of burying communications lines underground.

In Massachusetts, food supplies ran dangerously low in Boston, Springfield and Worcester as did fuel for heat. Most homes burned coal, but coal moved by rail and the trains were not running. Though the snow was heaviest in the rural communities of western and central Massachusetts, most residents took the weather in stride as they were accustomed to providing their own food and fuel. But for many farmers, the walk from the house to the barn became a life-threatening trek as whiteout conditions obscured the pathway and a miscalculation could cause a person to become lost in the deadly winds and cold.

People living in Massachusetts factory towns faired the worst. Those who failed to make it to work during the blizzard were docked a day's pay, and many who stayed home risked being fired. Several died trying to make the trek to work. One such victim was a North Adams man who froze to death a short distance from the mill; he was on his way home. The newspaper report suggested his cry for help was lost in the shrieking winds.

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

Now |

The BC Weather Book: |