Weather Almanac for February 2008

WATCHING THE SKY: WEATHER LORE

Long before computers and satellites, radiosondes and telecommunications became important ingredients in weather forecasting, people looked to the skies for telltale signs to indicate the coming weather. Fortunately, weather has many regular patterns and components that we can use to make a short-term forecast, a few hours ahead, the next day or two, and sometimes more. As Shakespeare wrote, "men must view the complexion of the sky to judge the state and inclination of the day."

The first to make weather forecasts were not scientists, but shamans and hunters, and then farmers, shepherds and sailors. Though they did not know it, many used the scientific method, based on observation, hypothesis building and testing the hypothesis. For example, when a certain kind of cloud was observed building through the day, rain likely followed. And since many whose life and livelihood depended on the weather were also illiterate, they condensed the hypothesis to an easily remembered saying or rhyme: If clouds rise in heaps of white, soon will the country of the corn priests be pierced with arrows of rain (Zuñi Tribe)

We collect the body of such sayings under the catch phrases of weather lore and weather proverbs. Some call them weather myths, implying that they are pure figments of an imagination, but that does a disservice to many which are truly scientific statements as true as "the sun rises in the east and sets in the west." The American Meteorological Society Glossary of Meteorology defines weather lore and weather proverb as: "Short, pithy, and much-used saying that expresses a well-known truth about the weather."

Weather lore likely loses some of its credibility because some of the sayings are based on religious grounds and others are based on supernatural instincts of certain plants and animals. Some plants and animals can give us fairly reliable forecasts, but mostly in the short term rather than for forecasts of coming seasons. Another reason that some lore is wrong in general applications is that the original observation were meant for a specific location or geographical setting. Many immigrant farmers to the American Middle West brought sure-fire weather sayings his father and grandfather had used in Germany or Sweden, but found them useless in North America. Weather lore derived for mariners often does not translate to mountainous terrain. And, tropical lore may not hold at higher latitudes and vice versa.

We can also find weather lore in many early and famous writings beginning with the ancient Greeks, particularly in Aristotle's Meteorologica and Theophrastus' On Weather Signs and On Wind. The latter two works contain some forty-five signs relating to wind, eighty for rain, fifty for storms, and twenty-four for fair weather. In his signs, Theophrastus used colors of the sky, rings and halos, and even sound as predictors. In the New Testament (Matthew 16.2-3) Jesus repeats one weather adage popular among sailors when he speaks to a group of fishermen: "when it is evening, you say, 'It will be fair weather, for the sky is red.' and in the morning, 'It will be stormy today, for the sky is red and threatening." Tis proverb can also be found in the sayings of English sailors:

Red sky at night, sailor's delight;

Red sky in morning , sailors take warning

A similar observation can be found in Shakespeare's poem Venus and Adonis:

Like a red morn that ever yet betokened,

Wreck to the seaman, tempest to the field,

Sorrow to the shepherds, woe unto the birds,

Gusts and foul flaws to herdmen and to herds.

The large number of weather sayings precludes my mentioning all in this piece. Indeed, substantial collections of weather sayings have filled hundreds of book pages. The Englishman Richard Inwards produced the first modern collections Weather Lore in 1869. The third edition released in 1898 contained 245 pages of British proverbs. This was soon followed in 1873 by the Reverend C. Swainson's Handbook of Weather Folklore that covered French, Germanic, Greek, and Italian proverbs. In North America, the Chief Signal Officer of the US Army, Major General W.B. Hazen issued an order to all Army post commanders to collect "popular weather proverbs and prognostics" in 1881. Two years later, Lieutenant H.H.C. Dunwoody compiled the collection as US Army Signal Service Notes Number IX. Since that time there have been many compilations of weather lore, and several of those offer opinions and supporting science as to the veracity of particular sayings.

A few years back, I participated in a CBC Radio call-in program where the listeners were asked to phone in their favorite weather sayings. Many sayings had some good science behind them, others were off the accuracy mark. One of the callers contributed this one: "If the bull follows the cows into the barn, rain will fall soon." Another listener remembered it slightly different: "If the cows follow the bull into the barn, expect rain soon." Such sayings have little scientific merit as weather forecasters, but one of the last callers had a more reliable, though slightly different twist to the two previous adages. He had heard (pun intended) that "If the bull follows the cows into the barn, expect calves."

Whenever someone tries to convince me that an adage with no scientific basis is true because they have seen an instance where it has been true, I am apt to reply with an adage of my own: "A stopped clock is right twice a day." And while no weather saying is 100% accurate, many can be tested and found to have an acceptable degree of accuracy as a forecasting rule-of-thumb. Many of the most accurate involve observations of clouds and wind as the predictor. Of the least accurate and usually useless are those that ascribe a long-range weather sense to animals and plants. In the short term, however, some animal/plant lore may be accurate as they too are able to sense approaching weather and react accordingly. For example, the more acute hearing of dogs may detect the first rumblings of thunder well before their owners, causing them to act anxiously for, as yet, no apparent reason.

A Look at Some Weather Lore

When scientists delve into an area of interest, they often take time to look at the phenomena and observe patterns that appear to recur. They then formulate a hypothesis such as a statement saying "if X happens, Y will result from it." This pattern recognition is the basis for empirical science (observation and testing). The statement is then tested against many further observations for its degree of accuracy. If the statement makes the grade, it is adopted as a useful tool, and may be used as stated or be the starting point for further investigations and refinement.

One need not be a trained scientist to use the methodology, and so many to whom weather played an important factor, such as sailors and farmers, became "amateur scientists." I am sure many of us who have lived in one location for a number of years have learned to recognize certain indicators that presage particular weather events and thus can formulate our own local forecast without the aid of the national weather service or other professional forecast group. I know that I have learned a rule or two about local conditions from long-time residents since moving to British Columbia that differed from those I had know in the Great Lakes region.

Look To The Sky

The weather adages that proved right more often than not became fixtures in the local community or certain professions and were passed down over generations. Many are still of great value today, and knowledge of them can make you weatherwise. The best (most accurate) were based on observations of the sky and the commonalities of weather systems as they passed over a region. It is not surprising that many of the observation-based weather lore provided early hypotheses in the art and science of meteorology and weather forecasting. Below, I look at several of the more accurate weather lore and cite the reason they are usually correct.

Here is a longer piece of weather lore which has much validity to those of us living in the Northern Hemisphere middle latitudes:

When the wind is in the east,

It's neither good for man nor beast.

When the wind is in the south,

The rain is in its mouth.

When the wind is in the west,

It suits everyone best.

In the classical model of weather fronts and low pressure systems moving across the middle latitudes, an east wind usually precedes a weather system that brings rains and cloudy weather. (Of course, the poem assumes a coming of rain and stormy weather is not a good thing. I am sure that during dry times, an east wind might foretell a good time for man and beast, but that is another topic.) The rain often falls around the low pressure system when the winds have a southerly component, particularly in the eastern portions of North America where southerly winds bring a moist component from the Gulf of Mexico and southern North Atlantic. Once the storm system passes, winds generally become westerly. It is then replaced by an approaching area of high pressure, and fairer weather ensues. The poem has a distinctly warm season bias since it considers the westerly winds suiting everyone. In a cold season scenario, west or northwest flow can bring in bone-chilling cold, and perhaps crippling lake-effect snows in some locations.

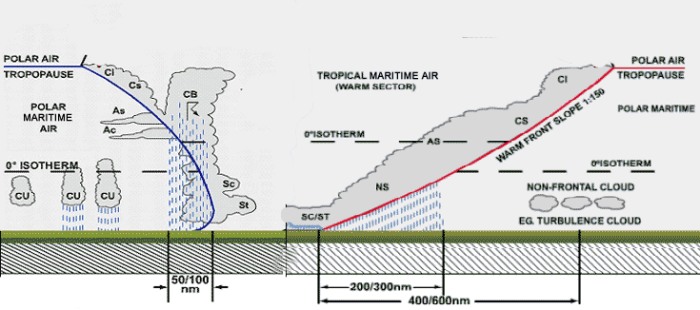

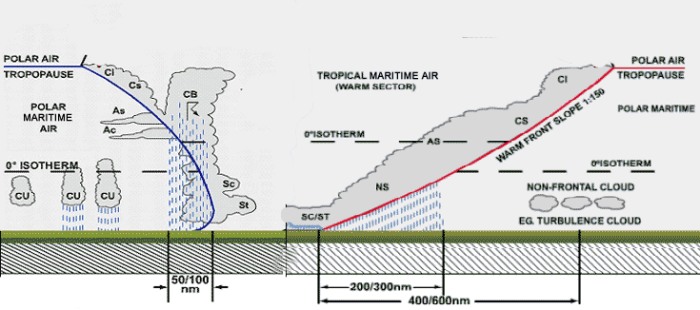

Classic Frontal Model

After diagram produced by British Meteorological Office.

Rain long foretold, long last,

Short notice, soon past.

Or

Long foretold: long last

Short notice: soon past

Again, in the classic frontal system model, the precipitation associated with the warm front gives ample warning and usually falls over a greater area and longer time period. In contrast, when the cold front approaches, the precipitation is usually associated with cumulonimbus clouds that arise at the front, giving little warning, and the precipitation is confined to a narrower space and short time frame. The second, similar adage can be explained as the first, or it could be an indication of the coming of a storm or storm system. A slow-moving cyclone may exhibit telltale signs for several days as moves toward a region and continues to move slowly as it passes over the region. A fast moving system such as an Alberta Clipper gives little warning and is past in a matter of hours.

Mare's tails and mackerel scales make tall ships carry low sails. Mare's tails and mackerel scales make tall ships carry low sails.

This adage from sailing lore links the classic frontal model with the cloud types typically associated with a warm front's approach. In this saying, mare's tails are cirrus clouds whose shape resembles a horse's tail and are the first indications of the approach of a warm front. Mackerel scales signify the presence of altocumulus clouds and indicate a lowering of the cloud deck as the front comes closer. A sailor noticing this sequence would know that within 12 to 36 hours, the weather would likely be wet and perhaps stormy. In such weather, he may think it prudent to stay in port or batten down the hatches for a blow, in other words, to "carry low sails."

Similarly:

When a halo rings the moon or sun,

Rain approaches on the run.

Halos form around the sun or moon when thin cirrostratus covers them. As with the mare's tails, cirrostratus are the early indications of an approaching warm front, and more likely than not, precipitation (which may be rain or snow...or both) is approaching. Similar sayings such as those below, are based on the same conditions:

The moon with a circle brings water in her back.

If the moon shows a silver shield,

Be not afraid to reap your field:

But if she rises haloed round,

soon we'll tread on deluged ground.

A silver shield signifies a very bright moon whose light is not diminished by intervening clouds, i.e., a clear sky. Such a night often foretells of a sunny day ahead, which would be good for harvesting. But if the halo is there, rain may be close behind.

But not all clouds foretell coming rain.

If wooly fleeces spread the heavenly way, be sure no rain disturbs the summer day. If wooly fleeces spread the heavenly way, be sure no rain disturbs the summer day.

If cumulus clouds are smaller at sunset than at noon, expect fair weather.

When the afternoon sky is filled with small cumulus clouds, like a flock of sleeping sheep, it is usually an indication of prevailing high pressure and therefore a small chance of rain. The second adage's reference to the clouds smaller at sunset than noon is further indication that their formation was due to daytime solar heating and not an advancing low pressure system. However, there are limits to the growth of these cumuli before the forecast changes:

When clouds appear like rocks and towers, When clouds appear like rocks and towers,

The earth's refreshed with frequent showers.

Should those small heaps grow into large rocks and towers due to solar heating and abundant moisture in the air, the likelihood of rain, via a thundershower or thunderstorm, may be in the offing.

Mountains in the morning,

Fountains in the evening.

Mountains in this adage refer to tall, billowing cumuli, which are indicative of atmospheric conditions conducive to the development of cumulonimbus clouds and, thus a late afternoon or evening thunderstorm is a distinct possibility.

The sudden storm lasts not three hours

The sharper the blast, the sooner 'tis past.

reminds us that such thunderstorms are often isolated and the product of daytime heating and thus not of long duration.

A clear sky can also give us weather signs. During spring and autumn (and winter in more southerly regions), this saying can be quite accurate:

Clear moon, frost soon.

A clear night sky allows more of the earth's surface heat to escape and thus the nocturnal surface temperature has a better chance of dipping to the frost point. A nocturnal cloud cover, on the other hand, slows the heat loss and may prevent frost formation.

Dew on the grass, rain won't come to pass.

This adage has a little less accuracy, but follows a line of thinking similar to the previous adage. When skies are clear in warmer weather, the loss of surface heat may drop the surface temperature down to the dew point. So if you see dew on the grass, it often indicates a period of clear weather, for a few hours at least.

A summer fog for fair,

A winter fog for rain.

This saying often is correct but is not infallible. Summer fogs most often form, like dew on the grass, during clear nights when the loss of surface heat drops the temperature of a larger mass of air to the dew point. When the air has been cooled, condensation forms in the air giving fog. Thus, a summer fog is often an indication of fair weather. In winter, fog is usually associated in the middle latitudes with a very low cloud deck near the warm front. In many cases, falling precipitation around the front raises the moisture level within the lower air mass until it reaches the condensation value and forms the fog.

Optical phenomena in the atmosphere can be associated with future weather conditions. As noted above, the halo may be a harbinger of precipitation. The rainbow is, of course, associated with falling rain, and its appearance in the sky can give an indication of what may follow.

Rainbow at night, shepherd's delight; Rainbow at night, shepherd's delight;

Rainbow in morning, shepherd's warning.

Rainbows always form opposite the sun. In the case of a rainbow at night — though more correctly, the adage should read "at evening" unless it is a moonbow — the sun setting in the west produces a rainbow from rain falling to the east of the viewer. Seeing a rainbow at this time may be an indication that the rain has moved past the observer's location and the sky is beginning to clear, an indication to the shepherd that the rain system has moved eastward and away from him (again in the Northern Hemisphere middle latitudes). When our shepherd sees the rainbow in the morning, however, the rising sun is in the east, and the rain clouds are located to the west and likely moving toward him. Thus a morning rainbow urges the shepherd and perhaps his flock to seek a sheltered location.

Winds can often indicate coming weather as related in the first weather lore poem given above. While the direction of the wind can be a very good forecasting tool on its own, when coupled with other information such as a barometer's pressure tendency, the accuracy of a forecast can be very high.

Yeller gal, yeller gal, flashin' through the night,

Summer storms will pass you by, unless the lightning's white.

I love the rhythm of this one and the image of heat lightning. Yeller gal refers to lightning that has a yellow hue. That yellow hue indicates the lightning light has passed through a substantial amount of air and has lost its blue hues. If the lightning is off in the distance, it is unlikely that that particular thunderstorm will pass over you. However, white lightning is close lightning and may be headed your way. Unless of course, it has already passed over.

Beware the bolts from north or west, Beware the bolts from north or west,

In south or east the bolts be best.

This expresses a similar observation based on thunderstorm location. Thunderstorms generally move from the north and west, particularly when associated with fronts. Thus, lightning seen in the north or west have a high probability of passing over the observer. However, lightning seen in the south and east indicates those storms have passed or will not pass the observation point.

When the wind backs, and the weather glass falls,

Then be on your guard against gales and squalls.

A steady, persistent fall in atmospheric pressure is often a good indication of stormy weather to come as an area of low pressure approaches. The likelihood of stormy conditions increases when the wind shifts from the west counterclockwise to an easterly component (northeast or southeast). Such a shift is known as backing.

Watching Plants and Animals

While weather lore based on observations of the sky and sea generally have a high degree of accuracy, those based on watching plants and animals fall into a lesser category of accuracy. I do not doubt that many animals, and some plants, can sense certain elements in their environment as good as or better than humans and thus react to changing conditions before we do. For this reason, some of our observations of plant and animal behavior can indicate coming changes in weather. Thus, we can interpret their weather sense and link the cause and effect into a saying. Some of the more accurate are:

A cow with its tail to the East makes the weather least,

A cow with its tail to the West makes the weather best.

The explanation here again employs the classic storm model. Cattle instinctively prefer to graze with their tails into the wind so that the wind can bring the scent of a predator to them (they can see ahead if a predator lurks there). East winds usually signify the coming of a storm system. West winds dominate after its passage and clear weather usually follows. Admittedly, the rhyme is poor and the wording vague in this one, but the concept is there. The explanation here again employs the classic storm model. Cattle instinctively prefer to graze with their tails into the wind so that the wind can bring the scent of a predator to them (they can see ahead if a predator lurks there). East winds usually signify the coming of a storm system. West winds dominate after its passage and clear weather usually follows. Admittedly, the rhyme is poor and the wording vague in this one, but the concept is there.

When chickens go to roost at day,

Expect the wet is on the way.

This likely has some degree of truth behind it, but I am not sure the chickens are specifically anticipating the change in weather directly. It is quite possible they are fooled by the thickening and dark clouds bringing the rain into believing that night is approaching and for that reason they go to roost.

Pimpernel, pimpernel, tell me true Pimpernel, pimpernel, tell me true

Whether the weather be fine or no.

The pimpernel flower closes its petals when the relative humidity exceeds 80 percent. Such high humidity in Britain, where the saying originated, generally signifies rain in the offing, or rain has fallen recently. Fair and sunny weather usually has low humidity. Thus a closed flower indicates rain, a closed one, fair weather. Other plants have similar responses to humidity, while some such as the rhododendron and laurel alter the angle of their leaves with changes in temperature.

Other observations link a plant or animal action caused by a precursor to a coming weather change. In these, it is not the plant or animal that senses the change but is affected by it. One that fits into this category is:

When leaves show their undersides,

Be very sure that rain betides.

In this example, it is not the plant turning its leaves over in expectation of the weather change, but a increase in wind gustiness prior to a convective rainfall that upturns the leaves.

Birds flying low, expect rain and a blow.

This fits into the possibly true category. Rain and stormy weather most often occur during periods of lower atmospheric pressure. Birds roost or stay close to the ground more often when the air pressure is low, perhaps due to the lower density of air making flight more strenuous. Others suggest the birds the lower pressure makes the birds uncomfortable in a similar manner to how we react to discomfort in our ears when changing altitude in a airplane or while driving in the mountains.

Can Weather Lore Be Accurate In The Long Term?

Most of the aforementioned weather lore can be quite accurate as short-term forecast tools, by which I mean they are useful in the time frame of an hour to a few days ahead. But many other weather sayings suggest longer term abilities (months to seasons) in their predictor. Most of these rely on plants or animals for their basis, while a few suggest one season foretells conditions in coming seasons. For example:

If autumn leaves are slow to fall, prepare for a cold winter.

It will be a cold, snowy winter if squirrels accumulate huge stores of nuts. It will be a cold, snowy winter if squirrels accumulate huge stores of nuts.

If the brown stripe on a Woolly Bear caterpillar is wider than the black stripes, the winter will be long and harsh.

A severe summer denotes a windy autumn.

A windy winter a rainy spring.

Warm summer means a cold winter, a dry spring means ample summer rainfall.

A windy autumn is followed by a mild winter.

None of the above have any scientific basis nor do they pan out in unbiased statistical tests. They seem to hold on because occasionally they are right by sheer coincidence. And often, like almanac long-range forecasts, they can be interpreted as being right by being vague. What is a severe summer that foretells the windy autumn? How cold is a cold winter since winters are by definition a cold season? And similarly, what degree of warm must a summer be to foretell a cold winter? And by logical thinking, A severe summer begets a mild winter.

There are several folk beliefs that suggest a specific period of time foretells the weather for the coming year. One version uses the twelve days of Christmas; another, the first twelve days of the new year. In such beliefs, the first day of Christmas/the new year presages the type of weather for January; the second, for February, etc. For example if the third day of Christmas is mild, so too will be the coming March. Again such beliefs have no basis in reality.

Many seasonal weather adages attributed to flora and fauna are actually similar to the season forecast based on a previous season. If squirrels accumulate huge stores of nuts, it is likely more an indication of a favorable growing year for the nuts rather than an inherent weather instinct in the squirrel who is more likely genetically programmed to gather as many nuts as possible. Thus, a squirrel accumulating huge nut stores is reacting the bounty of a warm summer, favorable for nut growing which by the last of the above seasonal connections indicates a cold winter.

I personally find it most interesting that many, including a large number in the media, will make a big fuss when one of these folksy proverbs or almanac predictions proves correct. And yet, they only seem to remember the blown predictions by the local weather forecaster. But then I get all annoyed when the media act like snow before the Winter Solstice is some abnormal event of nature.

A few weather-related, long-range folk predictions involving plants and animals may have some merit, but these usually predict some biological consequence from a seasonal weather observation rather than predict weather from some biological observation. For example, A year of snow, fruit will grow.

While not really a weather predictor, this and similar sayings may, in some areas and some years, be true. A snowy winter can increase the soil moisture level, thus reducing stress on a fruit tree or bush in the coming growing season. A snowy winter allowing snow to last into early spring may also delay the blooming of fruit trees until the danger of killing frosts has passed. A snowy winter also reduces the depth of frost penetration into the soil by insulating it and thus protecting the plant and its roots from cold damage. A continuous covering of snow also prevents undesirable freezing and thawing cycles of the ground that can damage wheat and other winter grains.

Final Word

Whether or not folk saying have some scientific basis behind its observations, I always find them fun to discover and ponder. I have found many of the old British sayings were more accurate when applied to Vancouver Island weather than Great Lakes weather. But then the two islands are more geographically alike than Britain and the Great Lakes — having an ocean to the west can be a big influence on your weather. If you are a reader from the tropical or subtropical regions, you may find that most weather adages are off the mark more often than not, since many of the soundly based ones derive from the concepts in the classic frontal model of mid-latitude storms.

What I admire most about the lore is the succinct, and often rhyming, wording of the adage. Of course, we know that putting information into a rhyme or song is often the best way to commit it to memory. (Think of how many songs or poem phrases you have running through your memory and yet you remember but few literary passages.) I also marvel at the folk science behind many of the adages. I always find it humbling to remind myself that people living many centuries past took the time to observe and theorize on the workings of the world around them, and did so without fancy instruments and computations. They did it using only their senses and brain power. I could say:

If you use your weather eyes,

You may become more weatherwise.

Learn More From These Relevant Books

Chosen by The Weather Doctor

- Horvitz, Leslie Alan:The Essential Book of Weather Lore, 2007, Readers Digest, ISBN 0762108576

- Sloane, Eric:

Eric Sloane’s Weather Almanac, reprint 2005, Voyageur Press, Stillwater MN; ISBN: 0896586804.

- Inwards, Richard: Weather Lore: A Collection Of Proverbs, Sayings And Rules Concerning The Weather, reprint 2007, Kessinger Publishing, LLC, ISBN 0548161003.

Written by

Keith C. Heidorn, PhD, THE WEATHER DOCTOR,

January 1, 2008

The Weather Doctor's Weather Almanac: Watching The Sky: Weather Lore

©2008, Keith C. Heidorn, PhD. All Rights Reserved.

Correspondence may be sent via email to: see@islandnet.com.

For More Weather Doctor articles, go to our Site Map.

I have recently added many of my lifetime collection of photographs and art works to an on-line shop where you can purchase notecards, posters, and greeting cards, etc. of my best images.

Now Available! Order Today! |

|

|

|

|

Home |

Welcome |

What's New |

Site Map |

Glossary |

Weather Doctor Amazon Store |

Book Store |

Accolades |

Email Us

|