|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Weather Almanac for October 2007TYPHOON FREDA: THE COLUMBUS DAY STORM

Born A Tropical StormFreda acquired its Canadian name because the air mass that spawned its storm core came from the western North Pacific out of a typhoon dubbed Freda. The first indications of a new tropical storm brewing appeared south of Eniwetok Atoll on 28 September 1962. The outflowing winds of that tropical depression organized over the succeeding days and became a tropical storm on 3 October whose center lay 500 miles (800 km) north of Wake Island. Initially moving northward, the tropical storm strengthened and became a typhoon (equivalent to a Category 1 hurricane) on 4 October. At that time, the storm received its name Freda. Now headed northeast, Freda peaked in wind speed at around 115 mph (185 km/h) and bottomed its pressure at 948 mb (29.99 inches Hg) over the next several days before dropping back to a tropical storm on 8 October. By the 10th, it was a tropical depression and with an influx of colder air began dissipating. But Freda did not die completely over the central North Pacific; there remained a spark of energy left in the storm remnants, enough to reinvigorate the low pressure cell. Somewhere between Hawaii and California, the remnants of Freda came under the influence of an upper-level trough and began to build. The spark of Freda flared up in an intense and rapid cyclogenesis known as a bomb on 11 October, and by the morning (0700 PST) of 12 October Freda was a strong extratropical storm with central pressure of 960 mb (28.3 inches Hg) located off the Oregon coast at 40N, 130W.  Storm Track of Typhoon Freda/Columbus Day Storm |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Moving rapidly eastward, the re-energized and intensified Freda first struck the northern California coast between Crescent City and Arcata at 1030 PST. It was a glancing blow as the storm center turned to move north-northeast up the coast. Subsequent analysis by US Weather Bureau meteorologists located the region of central pressure off the coastline about 50 miles (80 km) from shore until the storm hit the Strait of Juan de Fuca where it again turned eastward and crossed the spine of Vancouver Island. The storm and its trailing cold front produced strong winds and rains into California over the next day or so as far south as the Bay Area. San Francisco reported a 43-mph (69 km/h) sustained wind and 63 mph (101 km/h) gust. The greatest winds measured in California reached 54 mph (87 km/h) gusting to 71 mph (114 km/h) at Red Bluff with estimates of winds at Redding to be 58 mpg (93 km/h) gusting to 81mph (130 km/h). Heavy rains associated with the front forced cancellation of the World Series game between the Giants and Yankees. The rains caused major flooding and mudslides. In the San Francisco Bay Area, Oakland set its calendar-day record with 4.52 inches (115 mm) of rain on the 13th, and inland, Sacramento reported a daily record of 3.77 inches (96 mm). Oregon and Washington sustained the greatest damage from Freda's winds as the storm raced northward along the coast at around 40 mph. Coastal regions received the direct power of the gales, and although the rugged terrain along and inland of the coastal range cut the wind's fury in some places, it accentuated it in others, particularly in the Willamette and Columbia River valleys, and locally around gaps in the terrain and at higher elevations. |

Surface Weather Map for 12 October 1962 |

At Cape Blanco on the Oregon coast the sustained wind was estimated at 150 knots (173 mph / 278 km/h) by the local observer; the wind had already broken the anemometer. By mid-afternoon as the warm front associated with Freda passed Eugene, Oregon, the wind rose to 63 mph (101 km/h). Portland, Oregon would later record a similar sustained wind, while Salem, Oregon clocked a peak sustained wind speed at 58 mph (93 km/h). Even stronger winds occurred at Corvallis and Troutdale, Oregon: 69 mph (111 km/h). Later that evening (2057 PST), Seattle recorded a fastest-mile wind speed of 65 mph (104 km/h) at a downtown location. Elsewhere in Washington, Olympia, Toledo and Bellingham all reported sustained winds of 58 mph (93 km/h) while Tacoma and Everett recorded winds in excess of 50 mph (80 km/h).

And although the sustained winds were high, the gusts were more impressive. At Cape Blanco, a gust hit 179 mph (287 km/h) while one at Newport, Oregon reached 138 mph (221 km/h) before the wind sensor broke. Inland from Newport, the wind gusts at Corvallis hit 127 mph (204 km/h) shortly before the station was abandoned at 1615 PST; a later note on the observation form indicated on 13 October "Unreported from 04:00-12:00 due power failure and instruments demolished." At Eugene, the gusts reached 86 mph (138 km/h). In Portland, winds gusted to 116 mph (186 km/h) downtown and 104 mph (167 km/h) at the airport before the power failed. In Washington, Troutdale reported a gust of 106 mph (170 km/h). In Renton, the peak gust hit 100 mph (160 km/h), and the strongest gust at Bellingham just missed the century mark: 98 mph. A 90 mph (144 km/h) gust blasted Oak Harbor, and Whidbey Island, Washington. Four other locations in Western Washington measured gust in excess of 80 mph (128 km/h).

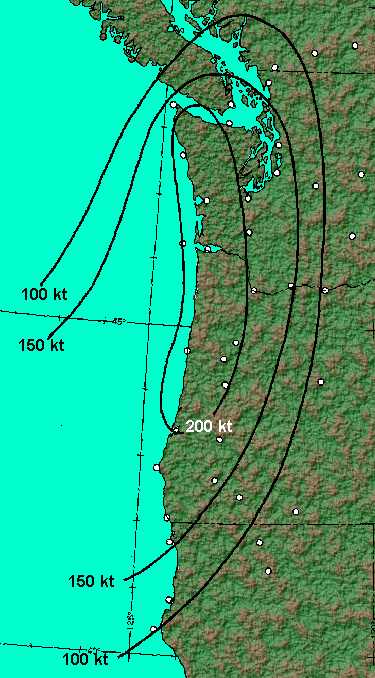

An analysis of the storm prepared by R.E. Lynott and O. P. Cramer (Monthly Weather Review, Feb 1966) suggests: "It is improbable, however, that these reports represent the true maximum winds over the area." One reason for this belief is that at the peak of the storm, there were intermittent power failures that compromised the measurements. In other cases, the observers were more concerned about personal safety than watching the anemometer dial as few instruments were self-recording in many observing stations. Lynott and Cramer used detailed pressure from sites within the storm's influence and determined an estimate of the geostrophic wind strengths across the region. Their calculations resulted in the map shown here of the regions of highest wind. The geostrophic wind assumes the wind speed results from a balance between the pressure gradient force and the Coriolis force. As a result, the calculation does not include impacts of surface friction nor local topography. They estimate that, when adjustments are made to the 20-ft (6 m) anemometer height, true wind speed values are about half the geostrophic value for 1-minute, sustained winds and 70 percent of the geostrophic for instantaneous gusts. The map below that they generated shows the estimated peak geostrophic wind field during Freda's passage. The central region of maximum winds reached or exceeded 200 knots (230 mph / 369 km/h) which corresponds to a surface wind of 115 mph (184 km/h) and gusts to 140 mph (224 km/h). The storm continued to move up the coastline and deepened slightly to 955 mb (28.20 inches Hg) (according to George R. Miller, Pacific Northwest Weather, 2002) before it began to fill. Its center at 1600 PST lay off the coast southwest of Astoria, Oregon. By 2200 PST, analysts placed the storm center, central pressure now 972 mb (28.70 inches Hg), off the coast west of the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Detailed analysis of the region by Lynott and Cramer showed a secondary low pressure region forming east of the Cascades over the Columbia Basin in north central Oregon around 1600 PST. |

Peak Geostrophic Wind Field (knots) |

Freda struck southwestern British Columbia around midnight following behind the storm that had raged across Vancouver Island and the Strait of Georgia about 18 hours earlier. Sustained winds reported at Nanaimo on Vancouver Island exceeded 30 km/h (19 mph), with a peak over 48 km/h (30 mph), for 4 hours on 11 October, while the peak wind reported there during Freda's passage was 31 km/h (19 mph). At Tofino, on the west coast of the island, wind speeds exceeded 40 km/h (25 mph) on the 11th for three of the post-noon hours with a peak of 56 km/h (35 mph) at 2 pm. In contrast, the peak observed winds associated with Freda were 32 km/h (20 mph). (Note that observations reported in the data base reflect only the sustained wind for a brief period just after the start or each hour and may not reflect the full nature of the storminess.) At Victoria, the winds on the 11th rose to over 40 km/h at 9 pm and did not subside until after 4 am the next morning, leaving a brief interlude between storms of less than 8 hours.

When Freda crossed the border into British Columbia, it raged over the Greater Victoria region on Vancouver Island and brought gale-force winds on the mainland through the lower Fraser Valley and particularly in the Greater Vancouver region just before midnight. Winds recorded in Victoria reaching sustained speeds of 90 km/hr (56 mph) with gusts to 145 km/hr (90 mph). Along Vancouver's coast, gusts reached 126 km/hr (78 mph) at Vancouver International Airport. Inland, the measured wind gusts reached 145 km/hr (90 mph) at Abbotsford.

Freda's winds reeked havoc along the Pacific Northwest Coast for around 24 hours, and like the tropical storms with which it shared an ancestry, it left a path of devastation behind, particularly in the great PNW forests. The estimated total loss of 15-17 billion board feet (35-40 million m³) for Freda, and its sister storms that struck on the previous and succeeding day, dwarfs the tree loss during the infamous New England Hurricane of 1938 when an estimated 2.65 billion board feet (6 million m³) blew down.

|

|

Forest and Tree Damage in Oregon. | |

Most of that destruction occurred in the forests of Washington and Oregon. As mentioned, the wind damage to timber resources was estimated at $750 million worth (around $5 billion 2006 US dollars) in the US, and about three quarters of that occurring in Washington and Oregon. The quantity of trees lost to Freda exceeded Oregon and Washington's combined annual timber harvest during that time. The winds also did damage to trees in British Columbia, most notably to Vancouver's famed Stanley Park — an estimated 3000 trees. There, the winds destroyed 20 percent of the park's old growth forest. (Similar devastation would occur in the park during the series of winter storms in 2006/2007.)

In Washington, efforts to salvage the downed timber swamped the capacity of the regional lumber mills. The State contracted a Japanese firm to remove and salvage "raw logs" from state-owned lands. This action set off a long and bitter political debate over the export of state timber. The four-year salvage effort resulted in approximately 350 million board feet ( about 790,000 m³) of timber being shipped to Japan.

The destruction to property began in Oregon where the storm damaged and destroyed buildings and downed power lines. The main transmission line towers that brought electricity to Portland fell before Freda's blast, knocking out power over a wide area. A Greyhound bus driver reported he had seen no lights on a trip through the Willamette Valley between Eugene and Portland. Some customers remained in the dark for several weeks following the storm.

|

|

Damage in Salem, Oregon. | |

The Red Cross estimated storm winds across Oregon damaged over 55,000 homes, 5,000 severely and 84 completely. Freda claimed an estimated 70 percent of the 4,000 houses within Lake Oswego located in northwestern Oregon. Winds channelling up the Willamette Valley destroyed or damaged most homes and farm buildings, in many cases crushing livestock within. In the valley, walnut and filbert crops sustained severe damage when the winds stripped unripened nuts from the trees and uprooted and split the trees.

When the storm hit the Oregon College of Education (now Western Oregon University) campus in Monmouth, it sent the Campbell Hall tower crashing to the ground. In Salem the storm winds damaged one in every three homes, and toppled the steeples on Christ Lutheran Church and St Paul's Episcopal Church. Winds also upset the Circuit Rider statue located on the Oregon State Capitol grounds in Salem.

|

|

The toppled statue of the Circuit Rider located on the Oregon State Capitol grounds. | |

The storm winds struck the Puget Sound area around 7 pm, and threatened visitors to the Century 21 World's Fair being held in Seattle. At 9:15 pm, Fair officials decided to evacuate visitors as a precaution but kept the Food Circus open all night to shelter fair-goers who preferred not to brave the elements. Falling trees toppled utility poles and snapped wires causing widespread power and phone service disruptions across Seattle and surrounding communities. Local ferry services stopped operations from 10:00 pm to 1:30 am after the Seattle to Bremerton ferry turned around at 9:30 pm and returned to dock because of the winds.

Around 9:30 pm Saturday, when Freda's winds punched into Victoria and southern Vancouver Island, they had been weakened only slightly by their encounter with the Olympic and Coastal Mountains. Nevertheless, they dealt the newly created BC Hydro and Power Authority's (now BC Hydro) transmission lines its most damaging blow of the century. Trees toppled from Sooke to Sidney, bringing down power and cutting off long-distance telephone and telegraph communications with the mainland. The gale snapped the eight 1.25-centimetre (half inch) steel mooring cables on a 38-tonne, four-engine Martin-Mars water bomber at the Patricia Bay Airport (now Victoria International Airport) and shoved it nearly 200 metres across the tarmac.

The wind's force shattered the display windows in the downtown Eaton's Department Store and scattered the Christmas display onto the street. Boats danced in the harbours, some breaking their moorings. Many trees including an immense old oak at Woodwyn Farm in Central Saanich were uprooted or broken. Late ferry sailings between the island and the mainland which had been delayed by 2 hours in the previous night's storm were cancelled, and the BC Toll Authority Ferries did not resume service until Sunday.

On the Mainland, the storm lasted about four hours, but hammered the Lower Fraser Valley .In Vancouver, BC, residents reported the winds howling like a jet engine while trees and utility poles snapped so rapidly it sounded like machine gun fire. Display windows of downtown department stores shattered under the force of the gale. The winds tore Vancouver's tallest church spire from the Evangelistic Tabernacle and dropped it into the sanctuary. In addition to the massive blowdown of trees in Stanley Park, nearly 1500 trees succumbed at the Vancouver Golf Club in Coquitlam, particularly on the back nine holes.

Half of the residents from Horseshoe Bay to inland Hope lost power, some for as long as five days. Property damage totalled $C55 million ($500 Canadian dollars in 2002 funds) and included boats and boat houses in addition to roofs and buildings.

The human tally from Freda numbered 46 in the US and 7 in Canada, with hundreds injured. The storm rates as the third deadliest weather-related disaster in the American Pacific Northwest during the Twentieth Century behind the Heppner Flood (Oregon) of 1903 and the Stevens Pass (Washington) Avalanche of 1910. Most fatalities in BC during the storm resulted from trees and poles falling on automobiles and crushing their occupants.

For further data and analysis of this storm, see these websites:

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now |

The BC Weather Book: |