|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||||||||||

Weather Almanac for January 2007THE LEGEND OF SNOWSHOE THOMPSONNow that I have relocated from the balmy (for Canadians) climate of southern Vancouver Island to the western edge of the Canadian Rockies, I find snow on the ground a way of life rather than an oddity of a few winter days. I have even relearned to drive on snow, though that is not hard in a very flat town with little traffic. Though we have had a snow cover for many weeks, neither the cumulated depth nor any single fall has made life intolerable. But watching the folks in the Denver region try to travel at Christmas again reminds me that snow is just naturally antagonistic to transportation. Okay, that is stretching it a bit. As I write, I hear the snowmobiles roaring through the nearby bush, and elsewhere I am sure folks are putting on snowshoes and skis to negotiate across ermine surfaces. But these folks are in the minority, and most who have to cope with snow and snowfall while traveling on aircraft, buses and automobiles are not happy travelers.  I am not far, as the raven flies, from the infamous Rogers Pass and the problems its deep and heavy snows have caused to the railroad industry here in British Columbia. I wrote earlier on the great avalanche disaster which befell the Canadian Pacific there nearly a century ago. In researching that story, I read accounts of the difficulties in building the transcontinental railroad much further south in the state we associate with sun and warmth: California. In the Sierra Nevada Mountains, snow depths of tens of feet often delayed work on the first rail line until late spring. In some instances, dynamite had to be used to open canyons clogged with snow to allow the workers to push the line through the ridge. Sierra Nevada winters have not only foiled the railroads, they were a hazard to all forms of land travel including foot travel. Settlers and 49ers alike suffered through the crossing of the Sierras on their way to the lush valleys and rich gold fields. One of the more infamous crossings was that of the Donner Party which lost nearly half of its 87 members to the deadly weather conditions in the Sierras. From the snows of the Sierras, however, a legend arose of a mighty man who gained his fame delivering the mail through the worst weather winter could throw at him. His name was John Thompson, but most know him simply as Snowshoe Thompson. The Man Behind the Legend

By this time, Jon Torsteinson-Rue had become John A. Thompson. Thompson settled initially in Placerville, California and mined at Kelsey's Diggings, Coon Hollow and Georgetown. Though he never became rich, he did earn enough from his claims to buy a small ranch at Putah Creek in the Sacramento Valley. Dan DeQuille of the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, a biographer and contemporary of Thompson described the 6-ft tall, 180-pound Norwegian as a "man of splendid physique. His features were large, but regular and handsome. He had the blond hair and beard, and fair skin and blue eyes of his Scandinavian ancestors."  The Sierra Nevadas near Lake Tahoe |

|||||||||||||||||

|

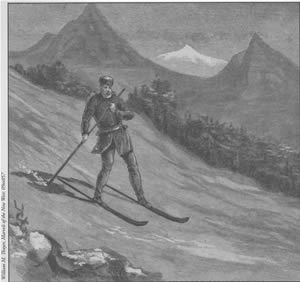

Knowing that traditional North American snowshoes had problems in the deep snows and steep terrain of the Sierras, John went back to his childhood roots and fashioned a pair of long skies that he remembered everyone used in the Telemark region of Norway. Called Norwegian skates, Norwegian snowshoes, and long snowshoes (ski was not yet a common term), the oak-wood skies were ten feet long and 4 inches wide at the front where they turned up. The pair weighed 25 pounds. He carried a single pole, which he generally held in both hands at once. His style was later described by Dan de Quille thus: "He flew down the mountainside. He did not ride astride his pole or drag it to one side as was the practice of other snow-shoers, but held it horizontally before him after the manner of a tightrope walker. His appearance was graceful, swaying his balance pole to one side and the other in the manner that a soaring eagle dips its wings." |

The day (3 January 1856) he left Placerville on his first mail run, some folks snickered at his ungainly equipment, and friends urged him not to go, believing the route too dangerous and his equipment too extreme. Few expected him to complete the run to Genoa, Nevada in the Carson Valley east of Lake Tahoe, a 90-mile trip. The legend has it that as he left, a local shouted in support: "Good luck Snowshoe Thompson." And the name stuck.

Thompson needed three days uphill to get to Genoa and two days to return to Placerville, amazing those on both ends of the route. He had negotiated the trip through complete wilderness, often traversing snow drifts 30 to 50 feet deep. With that first trip, Thompson became the only land communication between the Atlantic states and California and would remain the critical link for the next two decades.

The Sacramento Daily Union reported his arrival thus:

"Mr. John A. Thompson, who resides on Putah Creek, in Yolo county, left Carson Valley on Tuesday morning last, and reached this city at noon yesterday. Mr. T. is engaged in conveying an express to and fro from ‘the Valley.' Mr. Thompson was three days and a half in coming through Carson Valley, and used on the snow the Norwegian skates, which are manufactured of wood, and some seven feet in length. He furthermore states that he found the snow about five feet deep between Slippery Ford and the summit, a distance of eight miles, and on the average elsewhere in the mountains, three feet deep. Mr. Thompson left Placerville for Carson Valley on January 3rd, and leaves again on his transmontane trip this day."

When Thompson arrived in Genoa, the postmaster informed him he would need a contract with the US government to be paid for the work. The postmaster wrote his senator asking a contract be made, but none ever arrived. Though he carried the mail twice monthly during the winter for twenty years, Thompson never received a penny in payment from the US government. Sometimes, recipients of the mail would "tip" Thompson for his service, but otherwise all he ever earned was for specially requested deliveries.

The mail packs he carried weighed 60 to 80 pounds, and sometimes scaled over 100 pounds. Because of the weight of his mail pack, Snowshoe travelled light. He carried little food (dried sausage, jerked beef, crackers, and biscuits) and no blanket nor gun, but he did carry matches to start fires and his Bible. His water needs came from the snow beneath him. Those who saw him say he always wore a Mackinaw jacket and a wide rimmed hat. He covered his face in charcoal, reportedly to prevent snow blindness. When he needed to rest, he looked for a dead pine stump and made camp next to it. He would set the stump ablaze and, putting his feet near the fire, slept on spruce and fir boughs while resting his head on the mail pouch.

Later in his career, he would rest in caves or tree-root caverns on pine-needle beds, building a fire for his feet. If he found a deserted cabin, he would use it. A shelter he purportedly used during a blizzard, know as "Snowshoe Thompson's Cave," can still be found today. A flat rock resting atop two others to form a man-sized space is located off State Highway 88 in the Carson River Canyon just east of Hope Valley near Sorensens Resort.

If a storm hindered his travel, he reportedly would find a flat rock, clear the snow from it and dance Norwegian folk-dances until the storm blew over. He then continued on his way. Thompson claims, though he never carried a compass, he never got lost traversing the Sierra Nevada wilderness, where many landmarks lay buried beneath the snow, even in a blizzard. He once told a reporter: "There is no danger of getting lost in a narrow range of mountains like the Sierra, if a man has his wits about him." Thompson judged his direction by day from the flow of the streams and the appearance of trees, rocks and snowdrifts. By night, he navigated by the stars.

Snowshoe's usual route followed Johnson's Cutoff, a trail first marked by early explorer John Calhoun "Cockeye" Johnson. He first travelled up the canyon of the Carson River South Fork to its head, traversed the Sierra peaks through Johnson's Pass, and then skied down into the Tahoe Lake Basin. Next he forded the Upper Truckee River, crossed Luther Pass, traversed Hope Valley and plowed through the West Carson River canyon to Genoa. Today, this is the route of US Highway 50 from Placerville, California to South Lake Tahoe. de Quille noted of the route: "Not a house was then found in all that distance. Between the two points all was wilderness. It was a Siberia of snow."

Besides the mail, Thompson's mail sack carried medicine, emergency supplies, clothing, books, tools, pots and pans. Among the sundry items, many made life more tolerable to those living deep in the wilderness. He carried new strings for local fiddler Richard Cosser. For the widow Franklin, he carried a pack of needles and a glass chimney for a kerosene lamp so she could do her winter sewing. And piece by piece, he brought in the type and newsprint for Nevada's first newspaper, the Territorial Enterprise.

In 1858 with a few roads now being carved into the wilderness, Thompson did use horse-drawn sleighs where he could but still relied on his skis where the sleigh would not go.

While the act of carrying the mail through such hostile conditions was the basis for his legend, what Snowshoe Thompson did while making his treks cemented it. Heroic tales are told about his exploits during his mail runs. He aided many a stranded traveller out in the wilderness and often rescued prospectors caught out in the snow by carrying them out on the back of his skis as they held their arms around him.

One famous rescue occurred in the days before Christmas 1856. Thompson found James Sisson, a trapper, holed up in a deserted cabin for twelve days without food nor heat. Sisson's feet were half frozen, and he could not travel, even with Snowshoe's aid. Thompson chopped wood to heat the cabin, then set out for help. In Genoa, he found assistance but had to carve skis and teach the men to use them. When the five men had brought Sisson into Genoa by sled, the doctor concluded Sisson's feet needed amputation, but he had no chloroform to perform the operation. Thompson again headed out to bring back some chloroform, and finding none in Placerville, skied to Sacramento. Snowshoe Thompson brought the anaesthesia back to Genoa, and Sisson's life was saved. In total, Thompson had skied 400 miles in ten days.

In 1859, Nevada miners asked Thompson to carry some strange blue rocks that were devaluing their gold dust to Sacramento for assay. The rock turned out to be rich in silver ore, a strike known as the Comstock Lode which turned the California Gold Rush around as miners now streaked eastward for the silver fields around Virginia City and Reno.

For a brief time, Thompson carried mail from Cisco to Meadow Lake as the Central Pacific Railroad right of way was being constructed. During the severe winter of 1867-68, three thousand were caught at Meadow Lake City and spent the winter there. One, Clarence M. Wooster, described Thompson delivering their mail by sailing "down his four-mile course at great speed, cross the ice frozen river, throw our mail toward the house, and glide out of sight, up and over a hill, by the momentum gathered in the three mile descent." (California Historical Society Quarterly, 1939)

Wooster further noted how he and some kids decided to turn Thompson's frozen ski tracks into a sled run, shooting down the mountain like rockets: "The skis held to the track, but three of the kids went tumbling down a steep mountain." It is said that when Thompson heard of the incident, he located the kids and gave them a severe spanking.

The legend grew that nothing, neither blizzard nor cold nor pack of wolves, could stop Snowshoe Thompson on his appointed rounds. His story spread far and wide and continues being told today.

The late country singer Tennessee Ernie Ford recorded a song about Snowshoe Thompson that is included on his greatest hits albums. The song was co-written by Buddy Ebsen who later would go on to television fame in the hit shows The Beverly Hillbillies and Barnaby Jones.

When Thompson realized he could not make a living by carrying the mail, he homesteaded 160 acres in the Diamond Valley (near Marleeville in Alpine County) in the early 1860s and grew crops during the summer and carried the mail twice monthly in the winter. He raised mostly grains — wheat, oats — hay and potatoes. He once explained to his family that the only fruit he could grow was gooseberries and currents, due to the short frost-free period. During the winter, he tended cattle and horses.

As Thompson's fame grew, others living in the isolated Sierras were eager to learn about skiing. From his home, he taught them how to make and use his brand of cross-country skis. He often gave heart-stopping exhibitions of his jumps. As he raced down Silver Mountain toward the observers, he would spring up and over them, passing overhead with a wide smile. Accounts say he once skied 1600 feet in 21 seconds (55 miles per hour), and leaped 180 feet.

One story says Thompson met his future wife while giving her ski lessons. He married Agnes, Singleton in 1866 and settled on his homestead. They had one child Arthur Thomas, born on February 11, 1867. The story goes that Snowshoe was so eager to take his son "snowshoeing" that he made him a tiny pair of "snowshoes" for his first birthday.

Thompson was well respected by his neighbours and held public offices in both California and Nevada. From 1868 to 1872 he served on the Board of Supervisors of Alpine County, and was a delegate to the Republican State Convention in Sacramento in 1871.

Despite urging by the Nevada Legislature and the many political contacts he had made during his years carrying the mail, The United States Mail never paid Thompson for his work. So in 1872, he decided to go to Washington DC to see if he could collect his back pay. In keeping with his legend, the train Thompson was riding eastward was caught in a blizzard. Rather than wait, Snowshoe disembarked and walked the 20 miles to Laramie, Wyoming. Finding the train was not running there either due to the storm, he hiked 50 additional miles into Cheyenne to catch another. When Thompson finally reached Washington, he found that several eastern newspapers reported a man called "Snowshoe" had walked seventy-five miles through the mountains during a raging storm when his train became stalled and had reached Cheyenne two days ahead of the train.

But after a couple months of fighting the bureaucracy, Thompson gave up. He wrote Agnes, "I can't wait any longer. The men here are all very kind and I know they are doing all they can for me, but it takes more time than I can spare. I mustn't stay longer. I am needed at home for the ranch work." And returned home for the spring planting.

Despite the rebuff, Thompson continued to deliver the mail each winter. When he had thoughts of quitting, it is said, he would remember the look on the faces of those isolated men and women when he made his delivery, and continue on.

When he turned 49 in April 1876, De Quille described Thompson as in the prime of his life. "His eyes was bright as that of a hawk, his cheeks were ruddy, his frame muscular. His face had the look of repose, and he had that calmness of manner, which are the result of perfect self reliance." He still skied and would deliver a side of beef on his back to the miners working at the Pittsburg Mine, 20 miles south of his ranch.

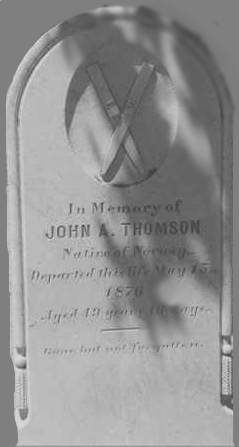

But in the Spring of 1876 while planting, Snowshoe Thompson suddenly fell ill (some accounts say he contracted appendicitis then pneumonia; others a liver disease, with the swiftness of his demise, I would conjecture a burst appendix) and died on 15 May at age 49. He was buried in the Genoa Cemetery. Arthur died two years later and was buried alongside him. Though Agnes remarried in 1884, she had a snow-white marble headstone placed on his grave in 1885. Carved in the stone were a pair of crossed skies and the words "Gone but not forgotten."

But in the Spring of 1876 while planting, Snowshoe Thompson suddenly fell ill (some accounts say he contracted appendicitis then pneumonia; others a liver disease, with the swiftness of his demise, I would conjecture a burst appendix) and died on 15 May at age 49. He was buried in the Genoa Cemetery. Arthur died two years later and was buried alongside him. Though Agnes remarried in 1884, she had a snow-white marble headstone placed on his grave in 1885. Carved in the stone were a pair of crossed skies and the words "Gone but not forgotten."

Genoa Postmaster S.A.Kinsey called him the "most remarkable man I ever knew, that Snowshoe Thompson. He must be made of iron. Besides, he never thinks of himself, but he'd give his last breath for anyone else — even a total stranger." Dan de Quille wrote in Overland Monthly: "John A. Thompson was the father of all the race of snow-shoers in the Sierra Nevada Mountains; and in those mountains he was the pioneer of the pack train, the stagecoach, and the locomotive. On the Pacific Coast his equal in his peculiar line will probably never be seen again — it would be hard to find another man combining his courage, physique and powers of endurance — a man with such thaws and sinews, controlled by such a will."

The Carson Daily News wrote of Thompson: "Compared with other men in snows and snowstorms, he was as much superior as the Saint Bernard is to the ordinary dog . . . Possessed of herculean strength, with nerves of steel and an iron will, and a heart susceptible of the kindest feelings, he was at once the beau ideal of strong manhood. ‘The bravest are the tenderest' . . . well applies to Our Man of the Mountains."

|

|

|

Statues of Snowshoe Thompson | ||

Today, a century and a half after that first mail run, Snowshoe Thompson is still remembered in the region where he delivered the mail. The Greater Genoa Business Association commissioned a statue for the Mormon Station State Historic Park in Genoa in his memory. Other statues and monuments in his memory can be found at Boreal Ski Resort on Donner Pass, in the Squaw Valley Village, and on Highway 88 along one his mail routes. A group The Heritage Association has petitioned for a commemorative stamp to be issued in his honour.

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now |

The BC Weather Book: |