|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| ||||||||||||||||

Weather Almanac for January 2005ICE TIMEJanuary is a time for ice across much of the North American continent. Here in Canada, much discussion around the table and across the media focuses on ice, or the lack of activity on it, as the National Hockey League season has not begun. For me, ice has many meanings and feelings, and for this month's essay I thought I would return to the topic in recognition the start of The Weather Doctor's eighth year on-line. My first posted piece dealt with ice storms, posted as the Great Ice Storm of 1998 aka the Quebec Ice Storm brought media attention to the weather.

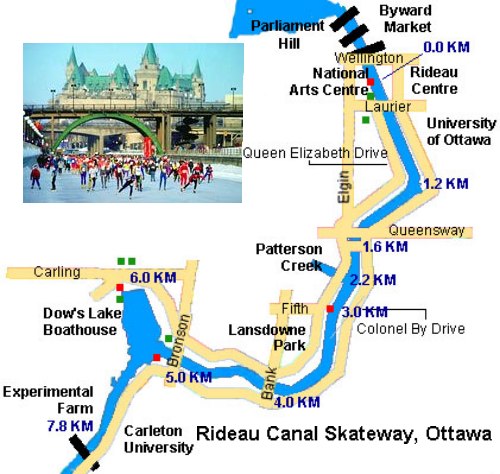

But this time, I look not at ice as a storm product nor in its most delicate form, the snow crystal, but as ice in sheets and blocks. The following material is a collection of essays written initially for the now-discontinued radio show The Weather Notebook which I had the pleasure of writing for over the past four years (two hundred plus scripts!). My thanks to hosts Dave Thurlow and Bryan Yeaton for giving me the chance to participate in this great endeavour. When January brings frozen lakes and rivers to Canada and the northern American States, folks are naturally drawn to the ice to skate, fish, and even sail. One of the great annual civic programs for public skating can be found in Canada's National Capitol: Ottawa's Rideau Canal. If we step back a century or more, before the days of widespread refrigeration, we will find that river and lake ice was a valuable commercial commodity. I give examples of this from New England, the Great Lakes, and the Chicago area. Ottawa's Rideau CanalSkating to work, Beavertails and hot chocolate, Winterlude. Each winter, a million residents and tourists enjoy the World's longest maintained skating rink through Canada's capital Ottawa. In 1970, Douglas Fullerton, National Capital Commission Chairman envisioned clearing a three-mile portion of the Rideau Canal through Ottawa for a large public skating rink. Today, many social and community activities including Winterlude, Ottawa's great winter festival, center on the Rideau Canal Skateway.  The Rideau Canal Skateway |

||||||||||||||||

Winterlude's Ice Hog Family |

Winterlude is hosted by the Ice Hog Family, Winterlude's loveable mascots, Mama and Papa Ice Hog and their children, Noumi and Nouma. Ice Hogs are magical, furry animals that, legend tells us, crossed an ice bridge over the Bering Strait from Russia to Alaska, and then they travelled deep into the Far North of what is now called Canada. Though related to ground hogs, Ice Hogs are much larger, and much more mysterious, and they love winter: the snow, the wind, the cold. Every year as winter winds down again, the Ice Hog community holds great celebrations to say farewell to winter, playing games, dancing and holding competitions for weeks. The festivities concluded, the Ice Hogs then turn in for the summer, hibernating within the permafrost or under a glacier until winter again returns to the land. Over a quarter century ago, Mr Ice Hog travelled down to Ottawa and arrived for Winterlude. So taken by the festival, he agreed to serve as the mascot, and the next season brought the whole Ice Hog family with him. |

Commercial ice harvesting ranked among New England's most important industries in the days before mechanical refrigeration and was a major American export in the 19th century ranking second only to cotton. Before electrical refrigeration became commercially viable, ice was a necessity for homes, hotels and restaurants. Local ponds provided much of the ice used for summer food preservation. When modern refrigeration technology ended the large scale export of river and lake ice, it did not end the cutting and storing of ice immediately. The industry lingered into the 1940s, and sporadic operations held on longer as many Americans considered "natural" ice to be healthier than the manufactured.

Commercial ice harvesting ranked among New England's most important industries in the days before mechanical refrigeration and was a major American export in the 19th century ranking second only to cotton. Before electrical refrigeration became commercially viable, ice was a necessity for homes, hotels and restaurants. Local ponds provided much of the ice used for summer food preservation. When modern refrigeration technology ended the large scale export of river and lake ice, it did not end the cutting and storing of ice immediately. The industry lingered into the 1940s, and sporadic operations held on longer as many Americans considered "natural" ice to be healthier than the manufactured.

In Maine, ice harvesting was an integral part of the state's winter economy as ice blocks from the Kennebec River were shipped worldwide. In 1815, the first ice shipped out of Maine came from Lily Pond in Bath. By 1886 the Kennebec harvest topped the million ton mark on ice production and remained there for a decade as many as 60 different companies tolled along the river. The great ice blocks, called Kennebec Diamonds, were shipped as far off as the Carribean and the Gulf States.

Even Walden Pond was harvested as Henry David Thoreau observed with annoyance: "Thus for sixteen days I saw from my window a hundred men at work like busy husbandmen, with teams and horses and apparently all the implements of farming, such a picture as we see on the first page of the almanac;..."

Ice Harvesting

Probably Lake St. Clair, Michigan circa 1905

(Photograph courtesy Detroit Publishing Company).

But New England was not the only major source of natural ice, the lakes and rivers of Wisconsin helped make both Chicago and Milwaukee famous. The thick, clear and clean ice of Wisconsin's many lakes provided a major local industry beginning with the rise of the railroads in the mid-Nineteenth Century. Harvesting operations close to railways efficiently delivered ice throughout the Midwest and South.

With the explosion of rail lines throughout the Midwest radiating from Chicago, Wisconsin ice could be shipped throughout the region. Its major users included the breweries of Milwaukee and Chicago's burgeoning meat-packing industry. At its height near the turn of the 19th century, nearly eight million tons of Wisconsin ice were shipped. In one year, breweries alone consumed three million tons to make and distribute beer.

The ice harvest was busiest during January and February, the depth of the Wisconsin winter, when ice thicknesses reached 45 to 75 cm (18 to 30 inches). Work crews often removed blocks weighing as much as 365 kg (800 pounds) each.

But the boom was short-lived. By 1920, mechanical ice making and refrigeration had removed the need for natural, winter ice, and the Wisconsin industry virtually disappeared during the unseasonably warm winter of 1920-21. One exception was the Soo Line railroad who did cut as much as 50,000 tons a year into the mid-1900s. Some farmers and resort owners continued to cut their ice in the mid-1900s.

An annual ice harvest still exists on Silver Lake outside Eagle River, Wisconsin. But it does not serve the beer or meat packing industries. It provides ice for the annual Eagle River Ice Palace, a popular, 6-m (20-ft) high attraction. Most winters since 1926, volunteers, headed by the local firefighters, cut and haul nearly 3000 30 cm (12 inch) thick ice blocks needed to construct the palace . Each block weighs 27-32 kg (60-70 pound) and is handcrafted to fit the design which has a different look each year.

Carl Sandburg called Chicago "Hog Butcher to the World." But the Windy City might not have reached such lofty platitudes without Ol' Man Winter's icy, helping hand and the many lakes north of the city.

The confluence of railroad lines around Chicago made it the ideal distributor of western livestock to eastern markets in the mid-nineteenth century. At first, railroads moved live animals, but economics soon showed it cheaper to transport dressed meat than live animals.

In winter, this presented no problem, subfreezing temperatures kept the meat fresh as it travelled east. Summer, however, was a different story because meat quickly spoiled under the heat within closed boxcars. George Hammond solved the problem in 1868 with a specially-designed railroad car, literally an ice-box on wheels, to send beef from Detroit to Boston. Chicago meat packers quickly adopted the concept, after all, they had been shipping ice by rail to their packing plants for several years in order to store dressed hogs arriving in winter through the warmer months.

At first, packers took their ice from the Chicago River but soon demand outstripped supply. That ice, like the river, was also horribly polluted, releasing sickening odors when it melted, and harbored dangerous bacteria. Importing ice from afield, solved both problems.

As a result, an ice harvesting industry grew in nearby northern Indiana and Illinois, then spread to Wisconsin's colder climate and abundant lakes as demand increased. Chicago's Swift and Company alone used 450,000 tons of ice annually.

The ice trade not only re-energized the pork industry, earning Chicago the title of "Hog Butcher to the World," it also revolutionized the beef industry, making fortunes for men such as Hammond, Gustavus Swift and Phillip Armour.

|

The centre of the stream now resembled a gorge as the water froze outward from both shores and the masses of ice were piled high on either side. At last, almost in an instant, the freezing waters seemed to solidify, and the entire channel was clogged with massive, up-ended cakes, jammed together in a solid, unmoving mass. — Pierre Berton, describing the freezing of the Yukon River near Dawson. From Winter |

In memory: Pierre Berton died in December 2004. His historical works were an important influence on my path to writing true stories from our history. |

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now |

The BC Weather Book: |