|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| ||||||||||||||

Weather Almanac for January 2004SNOWSHOEING THROUGH WINTERThe past month, I finally found time to get into a long-held book, The Last Place on Earth, which follows the race between Amundsen and Scott to attain the South Pole. I have read many books on the exploration of the polar regions and was drawn to finally read this one after reviewing Jack Williams' book: The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Arctic and Antarctic. One of the most striking aspects of the Amundsen-Scott race, and a factor in many of the British expeditions to polar regions, is the Brits failure to learn the skills and technology of the native peoples of the Arctic, which Amundsen adapted successfully. If you have ever trudged through deep winter snows, you can begin to imagine the difficulty of travelling through polar regions with common footgear — and I am not talking about shoes versus boots. I was a graduate student before I ever tried the specialized winter equipment of skis and snowshoes. I found both interesting methods of exploring the fields and woods near my home in Guelph, Ontario, though cross-country skiing eventually captured most of my outdoor winter recreation over the years. I admit that I found snowshoeing, using the large beaver-tail style shoes, cumbersome and requiring muscles that I did not use in other pursuits. But I am sure part of the clumsiness arose from lack of practice, I was definitely awkward on the skinny skis at first, and again each winter until I found my snow legs. I understand that modern materials have made the shoes much lighter, and other styles might have been more suited to southern Ontario woodlot conditions than the beaver-tails. As you may have guessed, I am focusing this piece on the snowshoe, in part because I feel it has deeper North American roots, tied with the Native Americans of the northern, but not always arctic, regions and adapted by fur trappers and mountain men. There were even snowshoe brigades formed during the colonial times prior to the American Revolution. OriginsLike many innovations, the origin of the snowshoe is lost in ancient times. Archeologists believe that a form of snowshoe or ski was in used at least six millennia ago in Mongolia, but some suggest they may be as old as 13,000 years and were used by the peoples crossing the land bridge from Asia to North America. What does seem likely is that the first pairs were simple attempts to imitate wildlife such as the snowshoe hare or ptarmigan or even the bear, who roamed snowy surfaces with little or no difficulty, and may have initially been conifer boughs attached to the feet. The first manufactured models were likely made of bent wood and animal skins.

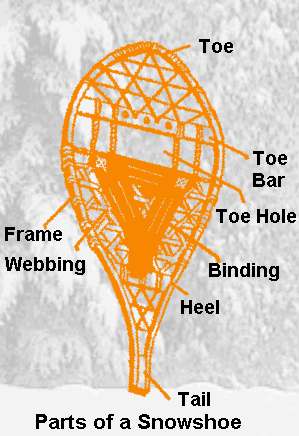

Wherever the origin of snowshoes, they spread across North America to the tribes living in snowy regions. (Skis did not come into widespread use until the immigration of Scandinavians in the early nineteenth century.) These peoples improved the design and often modified it to fit local conditions. A well-designed snowshoe effectively distributes the user's weight across a larger area of snow, thus allowing them to "float" on the snow surface. For example, where the snow is deep, extremely dry, and powdery, such as in eastern arctic/subarctic lands of Labrador and Quebec, the Montagnais, Cree and Naskapi developed the roundish beavertail shoes with tight interlacing. This wide design allowed hunters to traverse the deep powder snows. Some of these shoes measured over two metres (six feet) in length and 30-40 centimetres (12-15 inches) wide to allow travellers to transport heavy loads. Snowshoe StylesLong, wide snowshoes, however, were cumbersome in more rugged topography such as dense forests or rocky terrain, so peoples of forested or hilly regions made shoes that were smaller in both dimensions. Many resembled the wide, oval bear's paw, from which they take their name. In regions such as the western Arctic of Alaska and Northern Canada, the favoured design was the Athabaskan or Alaskan snowshoe that was long and more narrow than the beaver-tail. The basic shoe structure is illustrated below.  Parts of a SnowshoeToday, we group snowshoes into three basic styles: beaver-tail, bear paw, and Alaskan. The styles differ mainly in the shape of the frame and manner of the toe and tail. In its simplest, a snowshoe consists of a wooded frame holding a web of rawhide lacings or other material, known as the decking, and a means of securing the shoe to the foot, the binding and harness. The material and weave of the lacing varied with the groups that made the shoes, as was the size. Some newer shoe designs add a cleat, teeth at the bottom near the toe hole that provides added traction, particularly in icy conditions. The basics of the three styles are as follows:  Basic Snowshoe TypesBear Paw

Beaver-Tail (also known as Michigan or Maine style)

Alaskan (also known as Trail, Yukon, or Athabaskan)

The upturn of the toe, like that on a ski, prevents the shoe from digging into the snow surface with each step. The tail provides drag along the snow surface and can act as a rudder to keep the shoe straight when lifted. It can also be used as a brake in downhill regions by digging the heel into the snow. Many snowshoers add a pole or two for stability or added push — as in cross-county skiing — as an accessory. Snowshoeing Clubs of North America

and canoe. By the late 1800s, snowshoeing changed from a means of transportation to a means of recreation for many, particularly in eastern Canada, New England and the Great Lakes region. Released from a hard, demanding physical life in the booming industrial economy, many looked for new ways to play. As a result, snowshoeing clubs sprang up across the region. Minnesota supported more than sixty clubs, but they were imitations of the clubs that had grown up in Quebec around mid-century. Snowshoeing clubs wore colourful uniforms, based on traditional winterwear of the coureur de bois. Capotes made from brightly hued wool blankets were secured by a sash and complemented by matching toques and high leather moccasins. Colours on the uniforms often identified the club. In Quebec, blue identified the Montreal club, white those in Trois Rivieres and red for Quebec City.  Montreal Snowshoe Club, photo by William NotmanThe Montreal Snow Shoe Club began in the early 1800s when a group of sportsmen would challenge the harsh winter weather for an evening, torch-lit trek up the dark slopes of Mount Royal. There, the Tuques Bleues, so-named for the royal blue toques they wore, would enjoy a meal and fellowship, then descend the mountain en masse for home. As the club grew, so did its activities which included racing, obstacle courses, night tramps, snowshoe hill-sliding, and Sunday outings where the group would snowshoe to a member's home for dining, singing and socializing. Such clubs were not for everyone, in fact, they were only for a chosen few. According to Canadian author and historian Pierre Berton, the clubs were snobbish and highly exclusive, making their style of winterwear a symbol of high society. In Montreal, snowshoeing was reserved for the white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant male and was seen as a means of displaying male virility. When interest waned, the clubs began to turn from the active pursuit of sport to social-only clubs.

Written by

|

||||||||||||||

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now |

The BC Weather Book: |