|

|

| Home | Welcome | What's New | Site Map | Glossary | Weather Doctor Amazon Store | Book Store | Accolades | Email Us |

| |||||||||

Weather Almanac for June 2001WINDS OF THE DAY

As I sit here this early June morning, nary a breath of air stirs the now-verdant trees surrounding me. The only arboreal motion arises from the busy birds dashing from branch to branch searching for food to feed their nestlings, or returning to concealed nests with another morsel for hungry, squawking mouths. June is also a month when high pressure cells, both of continental and maritime origin, begin to dominate the weather patterns over most of North America. Those frontal-wave storms associated with the polar front have retreated far northward as the temperature differential between polar and tropical latitudes lessens with the lengthening days of Northern Summer. Weather map lows are now mostly shallow valleys between the sluggish high pressure cells sprawling over the map -- the col between the peaks -- or small dimples of thermal origin formed over the American Desert Southwest. June large-scale weather conditions provide the ideal environment for many thermally induced weather patterns such as the grand diurnal wind regimes of Summer. One common regime to coastal residents along ocean and large lake shores is the land-sea breeze (or land-lake breeze) circulation I have written about before, but similar heat-induced flows are also found on mountain slopes and in valleys. I confine my weather eye this day, however, a little closer to home, focusing into the realm of micrometeorology -- that field of study that looks into those atmospheric processes whose extent is less than a few kilometres in all directions. When this morning dawned, skies were mainly clear. I know that from the tell-tale patches of dew I observed upon awakening just after the sun had cleared the tree-line. Soon, its warming rays would strike the ground at a more concentrated angle, and daytime heating would begin in earnest. By mid-morning, pavement, some east-facing rock outcrops and patches of bare soil had become significantly warmer than the surrounding meadows, forests and lake. The air next to these hot surfaces would now also gain heat and in the process become lighter (less dense), a physical process known to us as Charles Law: as temperature increases, density decreases (at constant pressure). Eventually, such heating will produce nearly invisible "bubbles" of light, warm air and later plumes of hot air that rise skyward. I say "nearly invisible" because the observant eye can catch them altering any light rays that pass through, producing a shimmering or blurring of images behind them. And likely, I will also see small fair-weather cumulus clouds pop up where the thermal plumes reach their condensation level. If conditions of heat and humidity are conducive throughout the atmosphere, I may even be treated to a thundershower or two late in the day. But for now, my interest is riveted within the surface layer of the atmosphere -- that within a building's height of the ground.

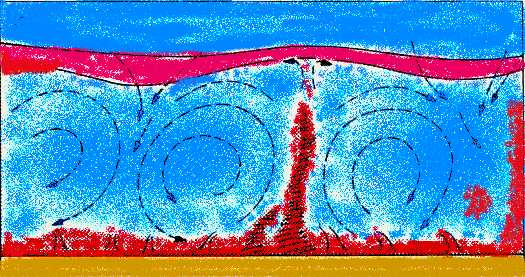

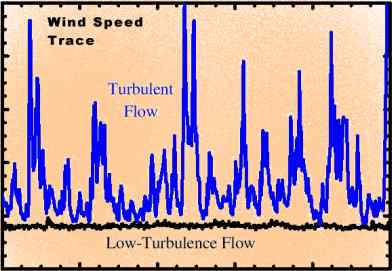

As these bubbles rise, the local air pressure of their spawning ground drops slightly relative to the air around it. As a result, a small pressure gradient is established between the thermal low- pressure spot and the surrounding air, and, as we know, a pressure gradient is the driving force behind the wind. Thus, air from the cooler surroundings blows into the low pressure spot where it too is eventually heated until it rises. Between the rising hot bubbles, cooler air sinks to replace the rising air, bringing with it not only cooler temperatures but also its higher momentum.  If we look out over a sunlit landscape and use a little imagination, we can almost see these bubbles and thermals rising into the sky like chimney plumes on a cold winter's morning: their size and shape varying with the terrain; their angle of rise varying with the wind speed above the surface. If we could colour the cold air, blue and the warm air, red, we would likely see a number of narrow columns of red air rising swiftly off the surface up into the atmosphere and broad regions of blue air slowly sinking in response. On a larger scale, such conditions can form the lake/sea breeze, upslope breeze and up-valley wind circulations. But on our microscale, rising bubbles and sinking air combined with mixing along the boundary (or microfront) between the warm and cold air make the movement of air chaotic, a flow condition called turbulent. The local wind thus gusts to higher speeds, then drops -- frequently to short-lived lulls -- and changes directions incessantly, often with abrupt reversals.  Under low turbulence, both speed and direction traces meander slowly, if at all, across the display or vary only within narrow confines. But increase the turbulence level, as it will on a sunny day, and both traces swing across the display as radically as the flight of a perturbed fly. The wind direction often fluctuates through the full compass of directions in a matter of seconds. If you have ever watched the time trace of wind speed and direction of a very turbulent wind on a chart recorder or video display, you will know what I mean.

Winds of the day do wrestle and fight, The "wrestle and fight" is the manifestation of the turbulence level observed in the wind as micro-changes in the heating and pressure fields of the lower atmosphere across a region cause air currents to vary in response. Throughout the day, the solar heating process continues, often altered by the movement cumulus humilis clouds born on rising air bubbles across the sky, causing shadows over the landscape. The wrestling winds gust up, change direction and then lull for a moment or two. The fight proceeds irregularly until the hours prior to sunset. Eventually, the setting sun's rays are again spread too thin to heat the ground above the surrounding air temperature, and the rise and fall of air parcels diminishes ceases altogether. Unless perturbed by larger scale weather patterns, the surface wind speed drops, soon becoming part of the calmness of evening. With continued clear skies and light winds, the earth's surface will lose heat and cool. In many locations, the cooling will produce cold air drainage winds that will fill low terrain spots with cold, dense air that further dampen the turbulence in the breeze until it is finally becalmed. The sun has set, and the day I had awoken too and watched so intently for so many hours has now ended. Hardly a leaf now rustles in the tree around me, even the avian activity has ceased for the night. The calmness of the evening ushers in a time for rest, a time for peace, as the waning June moon rises from the horizon. Learn More From These Relevant Books

|

|||||||||

|

To Purchase Notecard, |

Now Available! Order Today! | |

|

|

NEW! Now |

The BC Weather Book: |