As the great doors of the hall are flung open, a dramatic figure dressed in buckskins and leather

entered proclaiming, "How kola," followed by a few words in the tongue or the Ojibway nation

which he quickly translates to mean: "I come in peace, Brother."

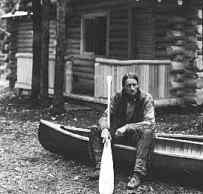

The man is Wa-Sha-Quon-Asin, "He Who Flies by Night," Grey Owl. The brother to whom he

speaks is George VI, King of England. This command performance before the British Royal

Family will climaxed a meteoric and often mysterious career championing the wilderness, for

within the year, Grey Owl, at age fifty, will be dead.

The man is Wa-Sha-Quon-Asin, "He Who Flies by Night," Grey Owl. The brother to whom he

speaks is George VI, King of England. This command performance before the British Royal

Family will climaxed a meteoric and often mysterious career championing the wilderness, for

within the year, Grey Owl, at age fifty, will be dead.

Who was this man who had come out of the Northern Ontario wilderness to take pre-war

England and North America by storm by exhorting the glories of the wilderness and the plight of

the beaver?

By his own accounts, Grey Owl was the half-breed son of Scotsman George MacNeill and

Katherine Cochise of the Jacarillo band of the Apache, born in Hermosillo, Mexico in 1888. His

father had been an Indian scout and friend of Colonel Bill Cody. In fact, his parents were

participating in Buffalo Bill's tour of England for Queen Victoria's Jubilee in 1887 when, in

Grey Owl's words, they returned to the United States with his "appearance threatening to

become imminent." At fifteen, he set out as a guide and packer in Western Canada. When silver

was struck in the Northern Ontario community of Cobalt in 1903, Grey Owl followed the rush

but was sidetracked and instead became a trapper and wilderness guide.

The shock, however, was to come a few hours after Grey Owl's death. The press had long

labeled him a "full-blooded" Indian despite his blue eyes, a fact Grey Owl never bothered to

correct. But Grey Owl was not a full-blooded Indian, nor was he even a half-breed. Grey Owl

was, in fact, born an Englishman, Archie Stansfeld Belaney, and reared by two maiden aunts in

Hastings, England. He would not see the true wilderness until he was 18 years old.

The repercussions of the revelation shocked those who knew him and drew damnation from the

press who felt they had been deluded by Grey Owl/Belaney. The truth about Grey Owl the man,

however, did not overshadow the truth of the message on which he spoke: the plight of vanishing

species, symbolized for him in the beaver. Belaney's nature writings still stand as classics of the

Canadian wilderness,.both in form and message.

The story of Grey Owl is as mysterious in truth as any fiction. As a child, Archie Belaney had

submerged himself in the study of nature and the tales of the North American Indian. His

childhood was introspective, and he inwardly rebelled against the stern authority of his Aunt

Ada, who wished to mold Archie into a gentleman so as to not become the irresponsible drifter

his father had been.

At eighteen, against the protests from his aunts, Archie broke his ties with England and

immigrated to Canada settling at first around Toronto. With the news of a silver strike near

Cobalt, Archie naively headed northward into the wilderness. His near total lack of practical

bush knowledge nearly killed him, but at the moment of his greatest distress, good fortune

placed him in the hands of woodsman Jesse Hood and a band of Ojibway, who took him in and

taught him the ways of the Ontario wilderness. For the next decade, Belaney trapped through the

winter and worked the summers as a guide or forest ranger. He never spoke of his past, and in

the tradition of the North Woods, no questions were ever asked.

With the passing years, Belaney relinquished his past life and adopted the life of the Native

Peoples he so admired. Soon his identity had become so throughly native that on his Army

papers, he was identified as a half-breed.

The Great War pulled Archie and others from the Ontario wilderness and threw them into the

savagery of the European battlefield. The sights and experience of war abhorred him. After

receiving a foot wound during combat and having his lungs seared with mustard gas, Archie was

released as unfit for further duty and awarded a pension. Brooding from the experience, Belaney

returned to his Northern Ontario wilderness.

Back in Ontario, the horrors of war took their toll on his temperament. Belaney developed such a

foul temper that his career as a guide was ruined. Total disregard for his own well-being nearly

ended his life on several occasions. But again, the Ojibway took him in. Under the care of the

venerable tribal elder Neganikabu, Archie Belaney was trained in the Ojibway manhood rituals.

His instruction culminated in his official adoption into the tribe. The Englishman Archie

Belaney was, for all practical purposes, dead. Born was Wa-Sha-Quon-Asin, "He Who Flies by

Night," Grey Owl, a man of the Canadian wilderness.

With his rebirth, Belaney/Grey Owl's disposition changed dramatically. His hatred of the white

man's world changed to indifference. And, with the return of his usual humour and self-confidence, Grey Owl's reputation as a guide was quickly re-established.

While working in the Temagami district of Northern Ontario in the summer of 1925, Grey Owl

met a young woman, Gertrude Bernard by name but called Pony. She was part Mohawk, a nation

within the Iroquois Confederacy. Her native name was Anahareo, the name by which she is

identified in all of Grey Owl's writings. Their brief first encounter stirred Grey Owl's emotions

as no one had before. By the winter, he could no longer be without her. In a letter, he asked her

to visit him. Anahareo came for a week but stayed for years, leading Grey Owl into the final

chapters of his life.

The tale of the transformation of Grey Owl from a successful trapper to wildlife conservationist

has been well-documented in his autobiographical book, Pilgrims of the Wild published in 1935.

During the winter of 1926, the trapping had been poor, and it left Grey Owl with meager

earnings. Reluctantly, he planned a spring hunt. It was such hunts that experienced trappers like

Grey Owl had long deplored, citing them as the prime cause of the rapidly declining beaver

population, for spring trapping invariably left many newborn beaver kittens orphaned to die of

neglect or be killed themselves in the traps.

Late one day, as Grey Owl was checking his trapline, he was abhorred to find three beaver

kittens and one missing trap. Upon relating the events of the day to Anahareo, he received an

intense rebuke from her. "You must stop this work. It is killing your spirit as well as mine." Grey

Owl knew she spoke the truth, but how could he earn a living if he did not trap?

The next morning, they canoed to the beaver lodge in search of the mother beaver who they

believed had been in the missing trap. Instead they found two orphaned beaver kittens. Grey Owl

and Anahareo adopted the pair, christening them McGinnis and McGinty. The child-like antics

of the "Macs" completely ended thoughts of future beaver trapping for Grey Owl. After a night

in which he slept with McGinnis cuddled to his neck, Grey Owl proclaimed himself: "President,

Treasurer and sole member of the Society of the Beaver People." His plans for the society

entailed finding a lake far away from trappers and there establishing a beaver colony and refuge.

Grey Owl and his "family" traveled to the Lake Temiscouata region on the Quebec-New

Brunswick border to find a remote lake on which to establish the colony and where he could trap

enough other fur-bearing animals to support the beaver project. Birch Lake, Quebec became the

colony site. There a cabin, later to be named the House of McGinnis and the scene of Grey Owl's

last book Tales of an Empty Cabin, was built. The area, however, did not support a fur-bearing

population of consequence, and Grey Owl could not make a living by trapping unless he broke

his vow to abstain from the beaver hunt.

Grey Owl and his "family" traveled to the Lake Temiscouata region on the Quebec-New

Brunswick border to find a remote lake on which to establish the colony and where he could trap

enough other fur-bearing animals to support the beaver project. Birch Lake, Quebec became the

colony site. There a cabin, later to be named the House of McGinnis and the scene of Grey Owl's

last book Tales of an Empty Cabin, was built. The area, however, did not support a fur-bearing

population of consequence, and Grey Owl could not make a living by trapping unless he broke

his vow to abstain from the beaver hunt.

To pass the winter, Grey Owl began to write accounts of the antics of the "Macs" along with his

general observations on the wilderness around him. Anahareo encouraged him to submit some of

these accounts for publication. Naively, they sent a manuscript to the editors of Country Life, a

British magazine for wealthy landowners.

Surprisingly, the material was well received by the Country Life editors. In March, Grey Owl

received a hefty cheque with the suggestion that the editors would be interested in a book-length

manuscript. Joyfully Grey Owl and Anahareo returned to their cabin, but the elation was to be

short-lived. At their cabin, the pair was met by their old friend Dave bearing a gift to help their

financial situation: the hides of the beavers from the Birch Lake colony!

In despair, they saw their hopes for a beaver refuge sink. And with spring break-up, the ultimate

sorrow descended on the pair. McGinnis and McGinty went out for an evening swim and never

returned. Though Grey Owl and Anahareo searched for weeks, no trace of the two beavers was

ever found.

Dave tried to console Grey Owl and Anahareo and obtain their forgiveness by presenting them

with two newly orphaned beaver kittens. At first Grey Owl was reluctant to accept them, but at

Anahareo's urging finally gave in. The male died after a few weeks, but the female seemed to

thrive in her new environment. She grew fat and domineering, and soon it became clear that this

beaver was to become the boss of the household. They named her Jelly Roll, but her bearing and

regal overseeing of events at the cabin earned her the title of the Queen.

Work continued to be difficult for Grey Owl to obtain, and the lack of money again faced Grey

Owl and Anahareo. By chance, Anahareo had found the opportunity to show some of Grey Owl's

writings to a Montreal woman, Mrs Peck. Impressed by what she read, Mrs Peck arranged a

lecture for Grey Owl. He as terrified at the prospect, describing his feelings "like a snake that

had swallowed an icicle, chilled end to end." His worries were for naught, however; the lecture

was a tremendous success, not only from an entertainment point of view, but also financially.

Grey Owl and Anahareo now had a bank account.

With the coming of winter, Anahareo left the cabin went north to prospect for gold. Grey Owl

remained at Birch Lake with Jelly Roll to write and to continue searching for McGinnis and

McGinty. He wrote several articles recording the life and antics of Jelly Roll and her new

consort Rawhide. It was during this winter that Grey Owl also wrote The Vanishing Wilderness,

his first book, published under the titled The Men of the Last Frontier in 1931.

Thereafter, events moved swiftly for Grey Owl. His articles and lectures brought him

considerable attention on both sides of the international border. The National Parks Service of

Canada took an active interest in Grey Owl's dream of a beaver sanctuary. They produced a film

The Beaver People that starred Jelly Roll. Now the Government of Canada was willing to

establish a beaver sanctuary in Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba. But Grey Owl,

Anahareo, Jelly Roll and Rawhide soon found that Riding Mountain was the wrong place for the

sanctuary. Grey Owl appealed to the Park Service for a change in location. As a result, the new

colony was moved to Lake Ajawaan in Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan.

Over the next three years, the colony grew and prospered as did Grey Owl's work. He penned his

book Pilgrims of the Wild as well as a novel based on the antics of the beavers McGinnis and

McGinty entitled Adventures of Sajo and her Beaver People. Grey Owl was soon known and

loved throughout North America and Europe as his books, articles and films met great success.

But for Grey Owl himself, life was going stale. He longed for the freedom of the backwoods.

Anahareo was restless as well and would soon leave Grey Owl and their young daughter to strike

out into the bush prospecting for gold. In 1935 when Lovat Dickson, Grey Owl's English

publisher and later his biographer, suggested a European lecture tour, Grey Owl consented

reluctantly hoping that the tour might buoy his failing spirits and refresh his mission.

The lectures were highly successful financially and well received although a personal nightmare

to Grey Owl. He felt "like a man standing naked upon a rock" when confronted by the huge

London audiences. The pressure of the press and public recognition gave him no rest. Perhaps he

was tormented by the false life he had been living. By tour's end, Grey Owl was a tired, old man

although only in his late forties.

The notoriety he gained abroad gave him no peace at home either. With great effort, he tackled

new projects including a movie about the Northern Ontario wilderness and, what was to become

his last book, Tales of an Empty Cabin.

In 1937, Grey Owl agreed to a second tour of Britain. The tour again appeared to be a brilliant

success, culminating in a private lecture to the Royal Family at Buckingham Palace. But with

each appearance, a little more of the spark and fire of Grey Owl the man dwindled. As each of

the 140 lectures he was to give in a three-month period passed, Grey Owl became less the

vibrant man and more the performing machine. Returning home across the Atlantic, Grey Owl

faced a twelve-week North American tour. During this lecture series, he predicted: "Another

month of this will kill me. If I am to remain loyal to my inner voices, I must return to my cabin

in Saskatchewan."

Shortly after returning to the log house beside the still frozen Lake Ajawaan, Grey Owl suddenly

fell ill. He was taken to the nearest hospital in a horse-drawn sleigh. There he was diagnosed

with pneumonia. Two days later, he fell into a coma, and by eight the next morning, Grey Owl

was dead. The medical staff were convinced his illness should not have been fatal. But with the

spirit had died the man.

To summarize the complex philosophy of Grey Owl into a single sentence would seem an

impossible task had not the man done so for us. In Tales of an Empty Cabin, he wrote: "Every

individual human being, every people as a whole, needs an aesthetic release; it is part of the

business of living, and aside from the arts, of which we have apparently so few, we will find it in

the lakes and streams and woodlands of our north as nowhere else."

Grey Owl's stated mission as the preservation of the Canadian wilderness in as natural state was

possible. Through the influence of McGinnis, McGinty, Jelly Roll and Rawhide, Grey Owl had

the perfect symbol of the vanishing wilderness -- the symbol of Canada -- the beaver. He saw

the decimation of the beaver population as a sign that civilization was encroaching too close

upon the wilderness. The traditions of wild places were being infested with the diseases of the

cities: theft, distrust, filth, a lack of understanding of the complex interactions of life in its

natural, wild state.

Grey Owl's stated mission as the preservation of the Canadian wilderness in as natural state was

possible. Through the influence of McGinnis, McGinty, Jelly Roll and Rawhide, Grey Owl had

the perfect symbol of the vanishing wilderness -- the symbol of Canada -- the beaver. He saw

the decimation of the beaver population as a sign that civilization was encroaching too close

upon the wilderness. The traditions of wild places were being infested with the diseases of the

cities: theft, distrust, filth, a lack of understanding of the complex interactions of life in its

natural, wild state.

As with many other hunters, trappers and backwoodsmen, Grey Owl had became one with the

wilderness and its creatures. It took but a small emotional event to awaken him to the

senselessness and tragedy of the hunt.

"Man's unfair treatment of the brute creation is too well realized to need a great deal of

comment.... Man's general reaction to his contacts with the animal world...are contempt or

condensation towards the smaller and more harmless species, and a rather unreasonable fear of

those more able to protect themselves.... Whole species of valuable and intelligent animals have

been exterminated for temporary gain." (Tales of an Empty Cabin)

Grey Owl's words re-emphasized those written less than a century prior in the backwoods of

Concord, Massachusetts by Henry David Thoreau. They also presaged the concerns of future

spokespersons for the wilderness and the environment.

"If we are to become a people of some account in future history, we must think of something

besides the dollar sign.... We need an enrichment other than material prosperity, and to gain it

we have only to look around.... Is not at least some of this great Northern heritage worth saving

in its original, unspoiled state, for such a worth purpose?" (Tales of an Empty Cabin)

Grey Owl was the product of many dichotomies. He was the romantic who as a youth dreamed

of the noble savage and the glories of the wilderness. Yet, he was also the realist who ran the

trap lines and lived the stark live of the Native American. He was born an Englishman but reborn

an Ojibway. He gave the appearance of an uneducated man, yet he wrote with the prose of

Thoreau mixed with the poetry of Whitman. A "devil in deerskins" yet a "St Francis of the

Indians."

In an age before pollution and acid rain befouled Northern streams, logging denuded uncounted square miles of woodland and species after species faced extinction, Grey Owl was a voice crying out of the Northern wilderness. Today the echo of his words still ring true as we enter an new age, an new millennium. His spirit still flies across the wilderness and we follow.

Order Grey Owl: Three Complete and Unabridged Canadian Classics from Amazon.com

The book contains three of his best-loved works.

The Men of the Last Frontier, Grey Owl's first book, was published in 1931. In this collection of stories, Grey Owl tells about his life on the trail, his Native friends, and their animal companions. In so doing, Grey Owl hoped to evoke sympathy and caring for the land that sustains us all.

Pilgrims of the Wild, published in 1934, is primarily an animal story, it also relates Grey Owl and Anahareo's struggle to emerge from the chaos that followed the failure of the fur trade and the breakdown of the old proprietary system of hunting grounds. This is a humble and moving collection that paints a beautiful picture of a quickly changing land.

Sajo and the Beaver People, published in 1935, chronicles the "beaver people" -- two beaver kittens rescued and adopted by an Indian hunter. The kittens soon become the beloved pets of the entire village. Their adventures and eventual reunion with their parents make this one of the most touching and irresistible stories in Grey Owl's body of work.

For complete biographies of Grey Owl, visit the Nature's Song bookstore.